Culture & Lifestyle

How two Sikhs built Kathmandu’s water pipelines and laid its roads

These sardars—who left an indelible mark on Kathmandu’s infrastructure—struggled with their conflicted identities in their new home.

Prawash Gautam

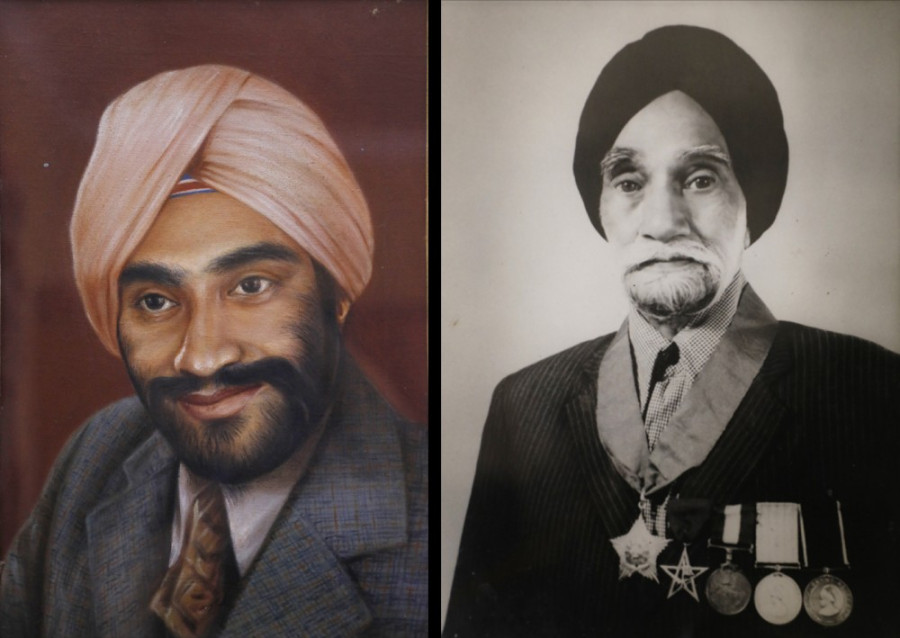

The saying goes that Sardar Manohar Singh could point to where each water pipeline had been laid under Kathmandu, and where all the valves and chambers and reducing holes were. Manohar—who came all the way to Kathmandu from Rawalpindi in 1931—knew all this for a simple reason: he had played a crucial role in laying them.

And when Kathmandu started tracing networks of roads above those very pipelines, it was Manohar’s son, Sardar Hardayal Singh, who would build paths and ensured their maintenance.

Well known in their lifetimes by government officials, ruling elites and commoners alike, for their pioneering contributions to Kathmandu’s water and road infrastructure, the father and son remain fresh in the city’s collective memory as turban-clad engineers with Nepal’s civil service. These two men, who settled in Kathmandu, left indelible marks on all of Nepal’s water and road infrastructure, but most notably in the Valley.

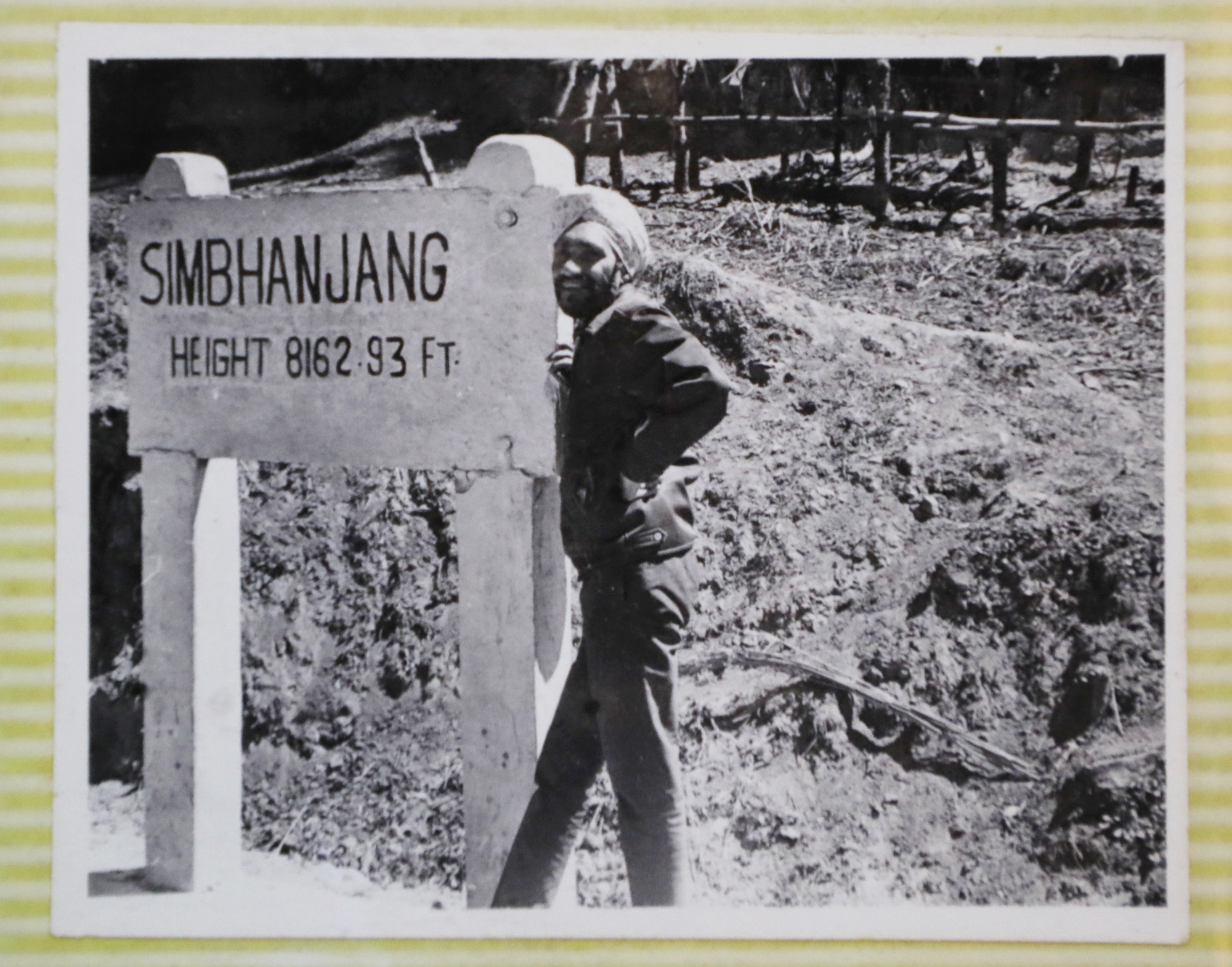

According to family members, the Kathmandu Water Works Department of Nepal’s government had called for applications for the position of overseer in advertisements in Indian newspapers, so distant relative Captain Basant Singh, another Rawalpindi Sikh working for Nepal’s royal family, encouraged Manohar to apply. Although he had the entire British Raj’s vast territory to choose to work, alongside an opportunity awaiting him in Iran, 33-year-old Manohar was attracted to ancient Kathmandu by the prospect of adventures of living in exotic Nepal. The country was still largely forbidden to the outside world.

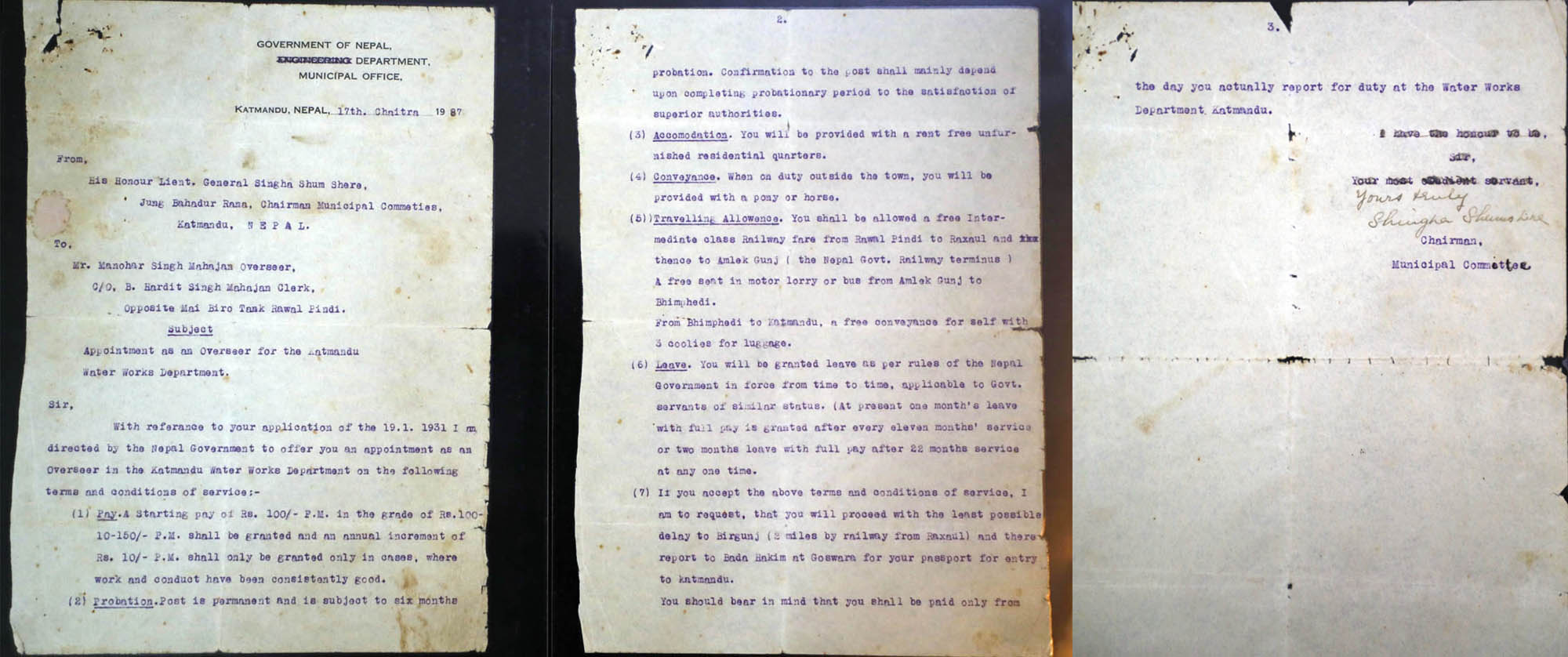

Manohar was filling an important position, with the job offer itself signed by Lieutenant General Shingha Shumsher, son of the preceding Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher and chief of the Kathmandu Municipal Committee. The letter, dated Chaitra 17, 1987 BS (March 30, 1931), and carefully preserved by Manohar’s family today, states in purple typewritten text all the facilities and respect Manohar would receive—paid transportation from Rawalpindi to Kathmandu, including the journey’s last leg from “Bhimphedi to Kathmandu [sic]; a free conveyance for self with 3 coolies for luggage”; a good starting salary by the day’s standard of Rs 100 per month; “rent-free unfurnished residential quarters”; and “when on duty outside the town, you will be provided with a pony or horse.”

But despite all these amenities, Manohar almost left as soon as he’d arrived, says 70-year-old Jagdish Kaur, Hardayal’s wife and Manohar’s daughter-in-law. Rawalpindi was cosmopolitan, while Kathmandu Valley was still closed off, a small semi-urban space existing alongside rural fields and villages.

Geographically and culturally, Manohar had little in common with Kathmandu. Few spoke Hindi, almost no one spoke Punjabi, and he didn’t speak Nepal Bhasa or Nepali. The food was strange, little like the roti, daal, rajma and variety of spicy achars his palate was accustomed to. A tall, young man, his favourite deep blue turban neatly fastened around his head and decked out in a cleanly ironed white Rawalpindi kurta shalwar, his fair face covered in a thick black beard, people found Manohar amusing. Jackals ran wild around his office in Tripureshwor, and his residence in Bagbazar, which, like many parts of Kathmandu then, was surrounded by wild bush. And—in a blow to the ego of the young and ambitious overseer—there were no tables or chairs in his office, only a sukul, as was customary at the time.

“It was all strange for him and naturally, a big cultural shock. So not long after arriving in Kathmandu, he felt homesick and lonely, and wanted to return to Rawalpindi right away. Basant Singh eventually talked him out of it, and he agreed to bring his wife and remain here,” says daughter-in-law Kaur.

Manohar—and eventually Hardayal, who was born in Bhonsi ko Tole in Kathmandu five years after his father’s arrival—would go on to make contributions at a time when engineering expertise was very rare, says Satyanarayan Manandhar, 83, a friend who studied and worked with Hardayal.

“When Manohar came in 1931, engineers could literally be counted on one’s fingers,” says the former divisional engineer at the Department of Roads. “The very fact that the Nepal government had to put up advertisements in Indian newspapers to bring in engineers from outside testifies to how the country lacked such human resource. Decades later, when Hardayal and I joined the government service in 1958, there must still have been no more than 15-20 overseers and engineers in Nepal.”

With their expertise, both father and son would go on to provide crucial knowledge and skills to develop infrastructure in Kathmandu and other parts of Nepal.

About four decades before Manohar’s arrival, Rana Prime Minister Bir Shumsher installed a piped water supply in Nepal by commissioning the establishment of the Bir Dhara in Kathmandu in 1895, which supplied water to Rana palaces as well as selected parts of Kathmandu through limited private and community standpipes. The system led to the establishment of the Pani Goshwara Adda (Office for Water Supply). Bir’s successors gradually extended the water supply to encompass newer settlements in Kathmandu and select parts of Nepal.

It was while this was happening that Manohar was appointed to the Kathmandu Water Works Department under the Pani Goshwara Adda. And although family members, friends and government officials are unaware of the finer details of where Manohar worked, there is general agreement he would have played key roles in laying networks of water pipelines in Kathmandu in this evolving system.

“Working as an assistant to a few engineers of that time, Manohar was involved in every single area of Kathmandu, laying its pipelines and building water systems,” Manandhar says. “He was also involved in developing water supply distribution systems in the Valley’s Rana and Shah durbars.”

Karna Dhoj Adhikary, 87, who returned with an engineering degree from India in 1955, was one of the first few chief engineers at the Department of Irrigation and Water Works. He remembers Manohar with admiration—for his dedication, diligence, and promptness in duty, along with encyclopedic memory of the extensive, complicated distribution pipe system laid decades ago not only in the cities of Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur, but also in Banepa and many other places of the country.

In fact, Manohar’s position was meant for not only the Valley but across Nepal, and at times, his deputations took him outside Kathmandu. Among his projects that family members remember is the construction of a drinking water facility on the premises of the Manakamana Temple, a system that exists to this day.

Manohar had been contributing engineering expertise to Nepal for about three decades when his son Hardayal returned from India with an overseer’s degree from Hewett Engineering School in Lucknow (he later completed an engineering degree from the same college) under the prestigious Colombo Plan scholarship, and joined the small pool of engineers and overseers in Nepal that his father was already a part of. Immediately upon returning in 1958, Hardayal was deputed at the Batokaj Adda–the precursor to the Department of Roads–where he would make important contributions in leading the construction, repair and maintenance of the road networks that weave through Kathmandu today, as well as of some highways across the country whose constructions were just being expedited in the 1950s.

Hardayal proudly listed in his curriculum vitae some of the notable works on road, water and other infrastructure he completed as the overseer and engineer at the Department of Roads, the Department of Water Supply, and the Water Induced Disaster Prevention Technical Centre (DPTC) under the Ministry of Water Resources. As the chief of Sano Gaucharan Road Division, he led the repair and maintenance of the Kathmandu-Sankhu-Sundarijal road, and of the Kathmandu-Airport VVIP road. Outside Kathmandu, he participated in the survey and construction of the Pattharkot-Thada road from Pattharkot in Sarlahi to Thada in Arghakhanchi.

Every monsoon, the Kathmandu-Bhainse stretch of the Tribhuvan Highway, a crucial lifeline to Kathmandu, would be torn off by landslides, hindering crucial supplies. Hardayal enabled vehicles to operate all year round through the bolstered maintenance of this section. He developed a water supply system to fulfil Tribhuvan University’s needs by building a reservoir to collect water from a stone water spout in Dhobighat in Lalitpur and channelling it to the University, and in 1997, he designed and constructed the Sankha Park at Dhumbarahi, which was once a popular park in the locality, but has now seen a decline.

How small the world of engineering was in Kathmandu and how important the role of the father and son duo is exemplified by instances of how often their works crossed each other’s, leading to sometimes light—but at times sour—squabbles.

Kaur, and her son 49-year-old Jeetendra Pal Singh, say that Hardayal often encountered a group of workers, mostly under his father’s instructions, digging up roads under his charge.

“He’d ask them to stop, but they’d curtly respond with ‘Our boss has asked us to not stop, no matter what happens’. With no option, he’d call the police and have them locked away,” Kaur recalls.

During lunchtime at home, sensing the lingering premonition of his father’s anger awaiting him, Hardayal would tiptoe in from the back door, peek into the kitchen to see if Manohar was still eating and enter only after ensuring he had left. But, of course, coming face-to-face was inevitable for father and son. The exchanges Kaur and her mother-in-law heard went thus:

“How dare you throw my men behind bars?”

“Pitaji, a permit from the Road Department is all they need before they start to dig. I’m compelled to have them taken away, even if to keep appearance before my colleagues and seniors. Please Pitaji, just a small permit…..”

“All our work has stalled because of you. And couldn’t you leave the shovels, other tools alone? You had to have them locked away too?”

“But our department has its own ongoing plans and works.”

“Now, don’t you start preaching to your father what to do and what not to."

“Not that Pitaji, but you can’t work without permission just because your son is in charge.”

The discussions often ended with Hardayal eventually relenting to his father and calling up the police station to have the workers released. But once, Kaur and Jeetendra say, the matter reached right up to the king.

“Once my husband had the police lock up the workers along with their spades and shovels and everything else they were working with. Just around that time King Birendra made a visit to the Department of Water Supply, my father-in-law’s office. He complained to the King that his son Hardayal had been repeatedly locking up his workers, thus creating obstacles in his work. In a light exchange, King Birendra told him that he didn’t want to interfere in the bau chhora ko jhagada. But eventually, he had his men coordinate with Hardayal and had the workers released,” Kaur recalls.

Because of their reputation as qualified engineers along with their unique identity as Sikhs in Nepal’s civil service, they were known in the palace, and among government officials and locals, says friend Manandhar. And whenever members of the ruling Rana and Shah families encountered problems related to water systems, or anything needing engineering support in their durbars, it was Manohar, and later Hardayal, that they sought.

......................................................................................................................................

[This is part II of the account of two Sardars, Manohar Singh and his son Hardayal Singh, in Kathmandu.]

Sardar Manohar Singh was so well known in Kathmandu, right from his early years here, that he picked up the term of endearment Babuji, among the Valley’s locals, government officials and even the ruling Shahs and Ranas. And so strong was his reputation that when his son Hardayal Singh also became an engineer, he was referred to as ‘Babuji ko chhora’.

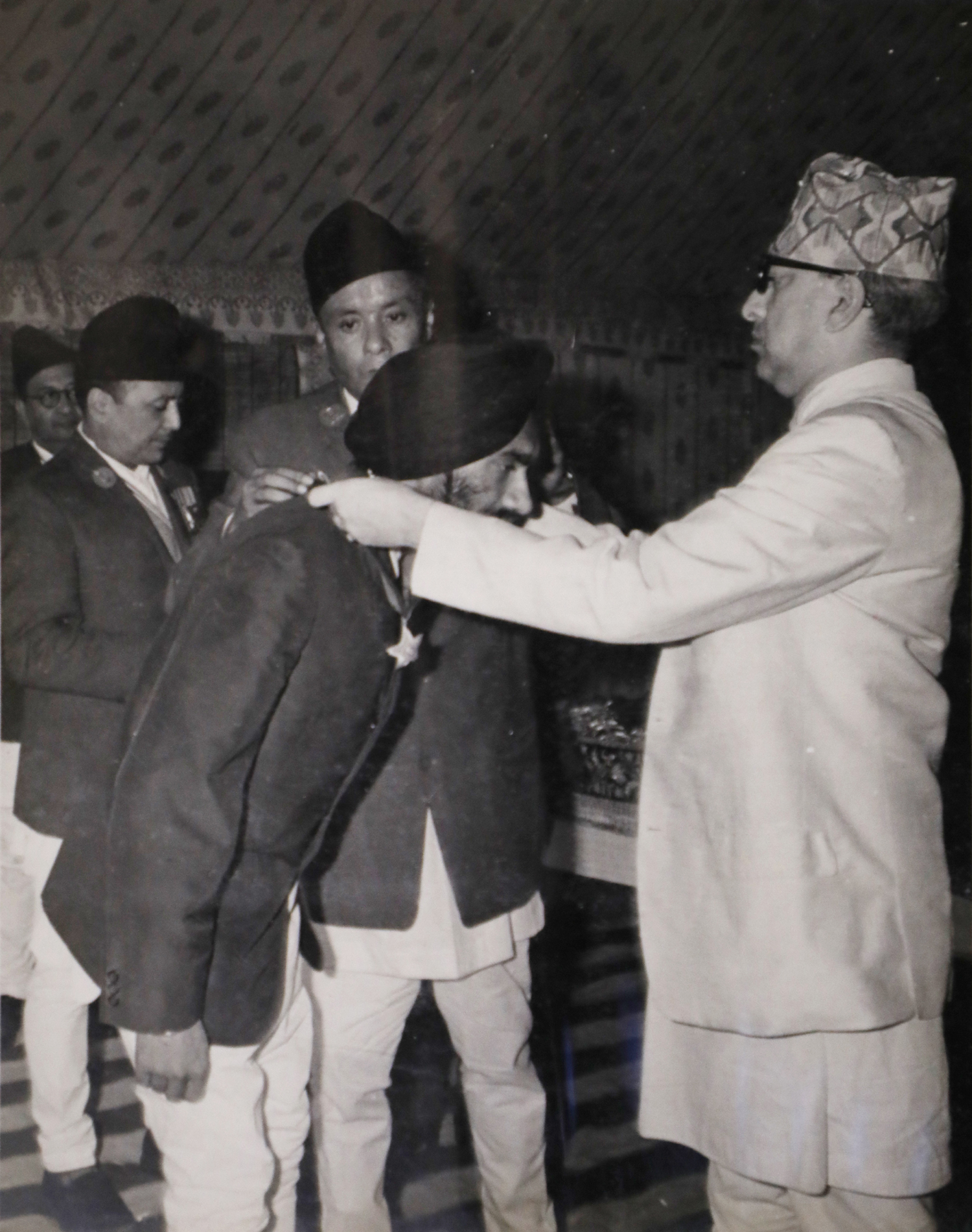

The endearment the father-son duo received from the public for their contributions was complemented by state accolades. King Mahendra decorated Manohar with the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu, one of the highest honours conferred by the Nepal government on individuals who make distinguished contributions to the country. In 1975, King Birendra too conferred the King Birendra Coronation Medal upon Manohar.

Likewise, King Mahendra bestowed the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu (Member Fifth Class) upon Hardayal in 1967. King Birendra also awarded him the Prabal Gorkha Dakshin Bahu Fourth Class (1974), Jaanapad Sewa Padak, King Birendra Coronation Medal (1975), Deergha Seva Padak, and King Birendra Silver Jubilee Medal (1997).

While the government accolades recognised their contributions to Kathmandu’s (and Nepal’s) infrastructure, what makes them more noteworthy, family and friends say, is that they came even as the father-son duo underwent personal losses and struggles of identity.

Manohar had decided to stay back and work in Kathmandu even when he’d wanted to go back. And he’d worked here for 42 years, knowing that his family and close relatives suffered back home in Rawalpindi.

The flicker of tension and bloodshed that eventually led to the Partition of India in 1947 had already begun when Manohar arrived in Kathmandu in 1931. In the subsequent years that tension would flare up.

“Every day, after work, he returned home to hastily tune in to All India Radio to listen to updates on rising tensions in India. What he and my mother-in-law heard was news of bloodshed, communal violence and people slashing each other with swords and knives, hawelis put on fire, and entire families and communities abandoning everything and leaving their homes to escape,” daugher-in-law Jagdish Kaur recalls them telling her. “What anguished their hearts more is that the tension was especially flaring up in the region where the border was eventually demarcated, and Rawalpindi lay near that border.”

.jpg)

In those tension-rife years, Manohar and his wife’s visits to Rawalpindi were few and far in between, and every time they were there, they tried to convince, in vain, Manohar’s family to come and settle down in Kathmandu. Eventually, as he committed to his work in Kathmandu, back home in Rawalpindi, his family, caught up in the troubles, was forced to desert all their property, their hawelis, and join the exodus to New Delhi in the early 1940s.

“Not being there with the family in that time of suffering always stayed with him. He had a sort of guilt for staying in Kathmandu’s comforts while the family suffered,” says Kaur.

Manohar had always waited for an opportune moment to go back and settle in India, along with his brothers and relatives. But, with the tension of Partition lingering into the 50s and 60s, that never happened. By the time the 70s came, he had been in Kathmandu for four decades, his children and grandchildren had been born, his son had a career here, and his wife had died and was buried here. Although he still longed for his family in India, by now, he had also grown attached to Kathmandu. And so, says Kaur, all the time he was laying down Kathmandu’s pipelines, his heart was torn between relatives in India and his new home in Kathmandu.

Hardayal, she says, perhaps faced much more profound struggles. And, as a long-time colleague and friend, Satyanarayan Manandhar closely witnessed this struggle.

“As it happens with turban-wearing Sikhs, the father-son’s Sikh identity was visibly evident to anyone. Since Nepalis don’t know much about Sikhs or Sikh Nepalis, their Sikhism often came at the expense of their Nepali identity,” says Manandhar. “People always looked with amazement and repeatedly asked Hardaya if he was a Nepali. And so, just because of the turban he wore, Hardayal found himself having to reinforce his Nepali identity throughout his life, something that made him sad.”

Once, to Hardayal’s delight, Patan locals celebrated him after he led the blacktopping of the road from Ga Bahal to Mangalbazaar in Patan. The locals appreciated him and his work, saying that despite being a foreigner’s son, he had done a service to Patan by blacktopping what had been a dirt road for so many years.

“My father was happy to receive the felicitation,” Hardayal’s son Jeetendra Pal Singh says. “But being referred to as the ‘son of a foreigner’ hit him hard.”

But the experience that hurt Hardayal most was when many years earlier, the issue of his Nepali identity had been touched upon by the king himself. As he put on the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu on Hardayal’s chest, King Mahendra had casually asked him, “Do you speak Nepali?”

“This naturally upset my father, given how inextricably the Nepali language was attached to the sense of Nepali identity during the Panchayat regime,” says Jeetendra. “More than that, the king himself had asked this question. And although it might have been said lightly, it still exhibited how his being a sardar always stood above his being a Nepali.”

Jeetendra says that repeated questions about his identity hurt Hardayal because he was born and grew up with his Newar pals in Bhonsi ko Tole, and was more fluent and comfortable in Nepal Bhasa and Nepali than Punjabi, his mother tongue. He had little contact with his relatives in India and had devoted himself to government service. Even until the final years of his life, on Saturdays and other holidays, he rode his motorbike from his house in Jawalakhel, through Tripureshwor to Bhonsi ko Tole, Kilagal and the surrounding Newari localities, to be among childhood friends.

“You won’t find a place as beautiful as Kathmandu. I’ll build a house here, in the outskirts, open and green all around,’ he’d tell me whenever I made repeated pleas to settle down in India, because that’s where I was born and grew up and had all my relatives,” Kaur says. “And he did just that, buying a piece of land in Jawalakhel, when it was really away from the city, and building a house here. That's why being referred to as Indian and having to prove his Nepali identity hurt him. Because he was a Nepali and had sweated in building Kathmandu’s roads, just as his father had in laying its pipelines. Kathmandu was where his spirit belonged, and he wouldn’t have been happier anywhere else.”

Manohar, says Kaur, had a straightforward manner of explaining this seemingly paradoxical identity struggle, attributing his and his family’s life situations to the larger designs of destiny. In the twilight of his life, Kaur often asked him, “Pitaji, what really motivated you to come here in Kathmandu, so far away from Rawalpindi, never to return, in spite of all your personal struggles?”

.jpg)

In his Punjabi, with an accent as strong as when he first left Rawalpindi six decades earlier, he would reply, “It must’ve been destiny that a sardarji had to come this far from Rawalpindi to lay down Kathmandu’s water pipelines, and for his son to build its roads. It must surely be destiny.”

Kaur says that it was by taking solace in this thought that the father and son had readily accepted their paradoxical situations and focused on their work, eventually making the contributions that they did.

Manohar retired following 42 years in civil service, in 1973, and Hardayal after 33 years, in 1991. A lot had changed in Nepal’s engineering field, especially after Manohar’s retirement, with engineering personnel increasing multifold over the subsequent years and decades. Newer generations of engineers and technicians at the Department of Water Supply worked to expand Kathmandu’s water system to meet rising demands in mostly crowded, unmanaged settlements that had sprung up above many of the same areas where Manohar had once assisted in laying down pipelines. Yet, they often turned for help to Manohar, who for them embodied something akin to a ‘living dictionary’ of Kathmandu’s water supply system, says Prayag Lal Joshi, 68, a former divisional engineer at the Department of Water Supply and later, chairperson of Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited.

When these officials appeared at his doorstep in Jawalakhel, right until his death at 94 in 1992, asking if Babuji could help them locate a particular pipe in a certain location, his face, then covered in a gray beard, would instantly light up. The tall sardar, wearing his deep blue turban as usual, still energetic and active in old age, would dutifully rise up and, as if fulfilling that call of destiny, graciously lead them to the site.

After his death, officials then came to Hardayal, until he died at the age of 70 in 2006. They’d ask if he knew about a certain old pipeline—just in case, because his father built them—because Hardayal himself must have, by chance, come across them when he traced or carried out work on the roads above many of those same pipelines.

Gautam is a freelance journalist with a special interest in social history.

21.02°C Kathmandu

21.02°C Kathmandu