Culture & Lifestyle

Forgotten in Kathmandu

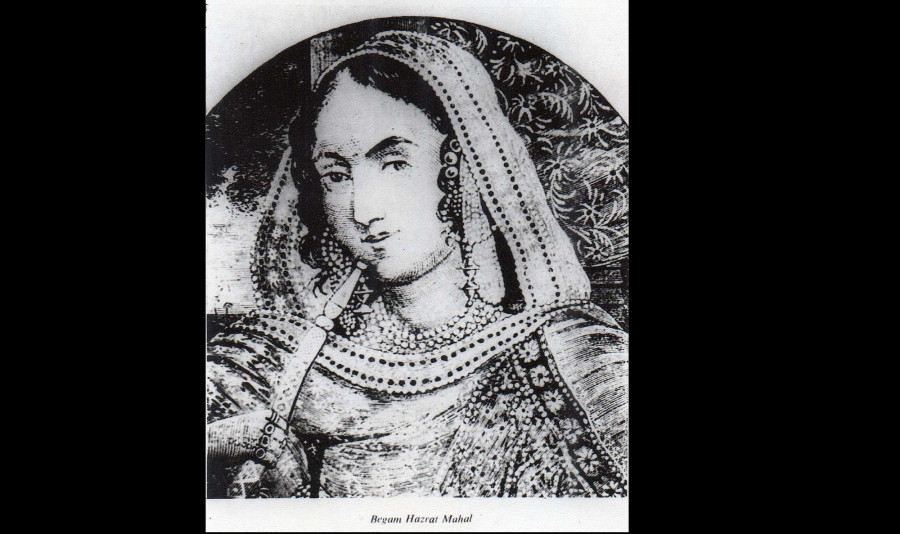

Indian freedom fighter Begum Hazrat Mahal and her son Birjis Qadr were exiled in Kathmandu for decades. But there's no recorded history and no one really knows about their lives in Nepal.

Prawash Gautam

A large framed black-and-white portrait of a bejewelled lady draped in flowing robes once hung on the drawing-room wall of Abdul Samim's home in Bagbazaar.

“Who’s she, grandfather?” Samim would often ask.

“She’s our queen,” Samim’s grandfather would reply.

Only once he had grown up would Samim learn the woman was the famed Begum Hazrat Mahal, the scourge of the British East India Company.

Mahal was the queen of Awadh, a princely state located in today’s Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, and a fierce participant in India’s first freedom movement, the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857.

In 1856, the British East India Company deposed Awadh’s ruler Nawab Wajid Ali Shah and exiled him to Calcutta with a promise of a life of luxury. His queen, Begum Mahal, however, enthroned their 12-year-old son Birjis Qadr, and fought the British valiantly for two years, before escaping and seeking asylum in Nepal. She came with a coterie of helpers and soldiers, among whom were Samim's ancestors.

“Jung Bahadur Rana gave asylum to the queen, and those who came with her lived in Bagbazaar and surrounding areas,” said Samim. “When the Begum died, she was buried on the premises of Jame Masjid. Later, her son Birjis Qadr returned to Calcutta.”

But that’s all that the 51-year-old knows about the Begum and her son’s lives in Kathmandu. In fact, it’s not just Samim. Other locals—whether it’s 49-year-old Mansur Hussain, 58-year-old Makbul Hussain, or 81-year-old Rahat Khan—don’t know much more either. Indeed, all that the members of Kathmandu’s small Muslim community—the community closest to Begum Mahal and Birjis Qadr—can say about the lives of these historical figures in the Capital are variants of the same story.

.jpg)

Some accounts, appearing in books such as Kumar Ghising’s Doon Ghati-Nalapani and Amritlal Nagar’s Gadar Ke Phool state that Begum Mahal was a Nepali. Sold as a slave girl to Wazid Ali Shah’s palace, they claim, she was inducted into the Nawab’s court, after which the nawab married her and gave her the title of Begum after the birth of their son. Her Nepali roots, this account states, was one reason why she chose Kathmandu as her place of asylum.

With no historically corroborating evidence to prove the Begum was Nepali, this is just one example of how bits of known information about her and her son’s Kathmandu connection are marred in obscurity while many important details have failed to pass down history entirely. All this in spite of the fact that Hazrat Mahal is revered as India’s freedom fighter. The details of her and her son’s life in Kathmandu could offer insight into the geopolitics of 19th century South Asia under direct rule or influence of the British Empire.

Forgotten grave and history

By 1950, a dearth of documented information about Hazrat Mahal and her son was already felt. In 1950 book Gadar Ke Phool, based on the oral history of the 1857 revolt, Amritlal Nagar, a literary figure from Uttar Pradesh, writes that “due to the lack of history on 1857 Mutiny written from the Indian perspective, the path of this history can be traced from oral tradition.”

A few years after the book’s publication, an incident would lay bare just how strongly Hazrat Mahal had been forgotten in the collective memory. The government of Uttar Pradesh, during its centenary celebration of the 1857 movement, honoured Begum’s compatriots Nana Rao, Tantia Tope, and Rani Lakshmi Bai, but did not even include Hazrat Mahal in the list of freedom fighters.

Concerned by the government’s lapse, in not recognising the Begum, Anjum Qadr, Kaukub Qadr and Nayyer Qadr, the three grandsons of Birjis Qadr, met with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and demanded the government rightfully honour Hazrat Mahal. On the family website, maintained by Qadr’s descendants, Anjum Qadr writes that during this conversation both sides were confronted by a striking revelation: neither the government nor the Begum’s family knew where her grave lay.

Eighty long years after she was laid to rest on the premises of the Hindustani Masjid (today’s Jame Masjid in Bagbazaar to the south of another mosque, the Kashmiri Takia), the Government of India and the queen’s family began their search for Hazrat Mahal’s grave. Under Nehru’s direction, the Indian embassy in Kathmandu promptly located the grave.

In 1959, Nayyer travelled to Kathmandu to visit the tomb and met Prime Minister BP Koirala, and requested that the government preserve the site. He also met local Muslims—as would Anjum in his visit in 1978—hoping to collect more details about the Begum’s life in Kathmandu.

“They couldn’t collect any substantial information, nor confirm bits of information they already had,” Calcutta-based Manzilat Fatima, Birjis Qadr’s great-granddaughter, told me.

And so, although the discovery of the Begum’s grave revived Hazrat Mahal’s connection to Kathmandu, it also opened a trove of unanswered questions about the queen and her son’s lives.

.jpg)

Conflicting details

Historians have little doubt that Jung Bahadur granted asylum and a monthly stipend to the queen in exchange for the jewellery she brought with her.

However, where Hazrat Mahal lived is less clear. Equally obscure is whether it was she who built Hindustani Masjid, which is now one of the two largest mosques in Kathmandu and the centre of Kathmandu’s Muslim community.

Jung Bahadur provided Hazrat Mahal with a residence called Barf Bagh, goes one account, which historian Purusottam SJB Rana’s book Shree Teen Haruko Tathya Britanta says was located in a spot called Dhikinakanira, on the premises of the Thapathali Durbar. Other accounts, such as Kazim Rizvi’s “Miserable condition of the grave of a warrior lady” published in The Milli Gazette, say she built her own palace, alongside an imambara (a Shia shrine) and a mosque (Hindustani Masjid).

Rana's account seems more plausible, given his book is based on a hand-written chronicle commissioned by Jung Bahadur himself. Yet, even the document doesn’t confirm if Barf Bagh was a temporary or permanent residence, which leaves ample room to speculate whether the queen could have been placed temporarily in Barf Bagh, and perhaps built her own residence later.

On the question of whether she built the Hindustani Masjid or only renovated an existing mosque? One version says the Begum, a Shia Muslim, built the mosque along with an imambara. In his article, Rizvi writes “Prince Anjum Qadar […] told me … that while in Nepal, the Begum built out of her own money, a palace, an Imambara and a mosque.” Other accounts supporting this version state she built these structures on land given by the government during the reign of Surendra Bikram Shah between 1847-1888. Information attributed to oral tradition in various writings like “The Muslims of Kathmandu: A Study of Religious Identity in a Hindu Kingdom”, a PhD thesis by Alfiani Fadzakir of Brunel University and historian Prakash Upadhya’s book Social Ethnography of Hill Muslims of Nepal.

The second version, such as the one mentioned in Sudhindra Sharma’s article “How the Crescent Fares in Nepal”, says Shia Muslims arrived during the reign of Pratap Malla, between 1641-1674, and were allowed to build a mosque to the south of the Kashmiri Takia. Hence, Hindustani Masjid was already in place when the Begum arrived and she only renovated it, while Sarfaraz Ali Shah, a mufti of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, who entered Nepal with the queen, converted Kathmandu’s Shia Muslims to Sunni Islam.

Albeit conflicting, these pieces of information regarding Hazrat Mahal and her son’s time in Kathmandu have mostly surfaced in writings. However, other important aspects of their lives here remain ignored or unexplored.

.jpg)

Uncharted freedom fighter-spirit

One unexplored aspect pertains to if Hazrat Mahal truly forsook her desire to reclaim her land from the British after taking asylum in Kathmandu.

Hazrat Mahal had sought asylum as a last resort, after her two-year effort to defeat the British failed.

Meanwhile, by giving her asylum, Jung Bahadur had invited British wrath, but had managed to convince the colonial power by arguing that it was against Hindu values to turn away anyone who seeks help. He had given the Begum asylum under the condition that she strictly refrain from engaging in any political activity.

But did this really quell the fighter in the queen? Did she remain in touch with other rebelling leaders in India?

Particularly important, but unexplored, is her interaction with Queen Jind Kaur of the Sikh Empire. Battling the British after the death of her husband Maharaja Ranjit Singh, she had gained a reputation as a valiant fighter before being captured and imprisoned. But she escaped, and hoping to forge an alliance with Nepal’s Rana and Shah rulers, came to Kathmandu in 1849 and briefly lived at the house of Amar Bikram Shah, son of Chautariya Pushkar Shah. Later, she sought asylum from Jung Bahadur Rana, and had already been in Nepal for 10 years when Hazrat Mahal arrived.

Despite the fact that both women were united by a common spirit, whether they communicated remains unknown.

Unexplored life of Awadh’s last Nawab

Another important but unknown aspect is Birjis Qadr’s life in Kathmandu. Birjis Qadr was only 14 when he came to Kathmandu as the exiled heir apparent to the kingdom of Awadh, and this is where he would spend almost all of his life. But even still, only snippets of information exist.

In 1869, Birjis married Nawab Mehtab Ara Begum, granddaughter of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, whose son had also taken asylum in Kathmandu. In Gadar Ke Phool, Nagar writes that the couple had eight children, five of whom were to die by the time the family left for Calcutta.

A poet, Birjis organised mehfils in which fellow poets from the queen’s coterie and Kathmandu’s locals participated. Khwaja Muhammad Moazzam Shah Raza Niyazi has preserved a handwritten diary written of his great maternal grandfather—one of the mehfil’s participants—which contains Birjis’ gazals.

“The diary could contain more bits of information on Birjis Qadr’s social interactions and poetry pursuits, but we can know this only when its Urdu and Persian texts, written in complex calligraphy, are decoded,” said 86-year-old Niyazi.

These snippets of Birjis’ life only indicate the broad facets of his life experiences. Crucial questions remain unanswered: What was it like for a teenage nawab growing up in exile? How was his family life in Kathmandu?

.jpg)

Broken links

How could the details of the lives of one of India’s revered freedom fighters and her son in Kathmandu get lost?

“Of course, details of Hazrat Mahal and Birjis Qadr’s times in Kathmandu must have been passed down orally among Kathmandu’s Muslim community,” said Samim. “But decades later, interest might have faded and details got lost as the community became occupied with their own lives.”

What about Qadr and his family then? Wouldn’t Qadr and his wife and children, who grew up in Kathmandu, have passed down memories of their life in the Capital?

“It’s only natural to believe that they would have,” said great-granddaughter Fatima. “But Birjis Qadr and his children, save his pregnant wife and one daughter, were murdered within months of arriving in Calcutta, breaking that Kathmandu connection too soon.”

Birjis’s father Wazid Ali Shah died in 1887, and the same year the British government pardoned him on Queen Victoria's golden jubilee. In 1892, the nawab arrived in Calcutta. Family accounts state in August 1893, Qadr’s relatives, who felt threatened by claims the nawab made on his father’s pensions and inheritance, hosted a dinner for him and his children where they were poisoned. Only his pregnant wife and a daughter who had not attended the dinner due to illness survived.

“Mehtab Ara and her children’s lives were clearly threatened, and she literally stayed in hiding from her relatives in the following decades,” said Fatima. “She raised her children cautiously, careful not to share too much information about the Begum and Birjis Qadr, lest their lives be at risk. By the time the situation became safer for my great grandfather and his children, many details were already lost. Given they lived in Kathmandu for so long, we cannot help but be curious about their lives there.”

And so, in April 2017, when Fatima and her siblings were in Kathmandu to commemorate Hazrat Mahal's 138th death anniversary, she spoke to some local Muslims, hoping to unearth anything new about the queen.

“Nothing came out of it,” she said. “Nobody seemed to know anything significant.”

Given the circumstances, a question naturally arises: Are the decades of lives of India’s noted freedom fighter and her son, Awadh’s last Nawab, in Kathmandu really lost?

“You can never tell,” said Fatima. “The Begum’s grave was forgotten for so long that even family members learnt about its location after eight decades. Their stories might be lingering somewhere in Kathmandu in the forms of documents, oral history, and bits of information, all waiting to be unearthed and recorded.”

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu