Culture & Lifestyle

Kathmandu’s first cups of tea

Trajectory and tales of Kathmandu's early tea experience.

Prawash Gautam

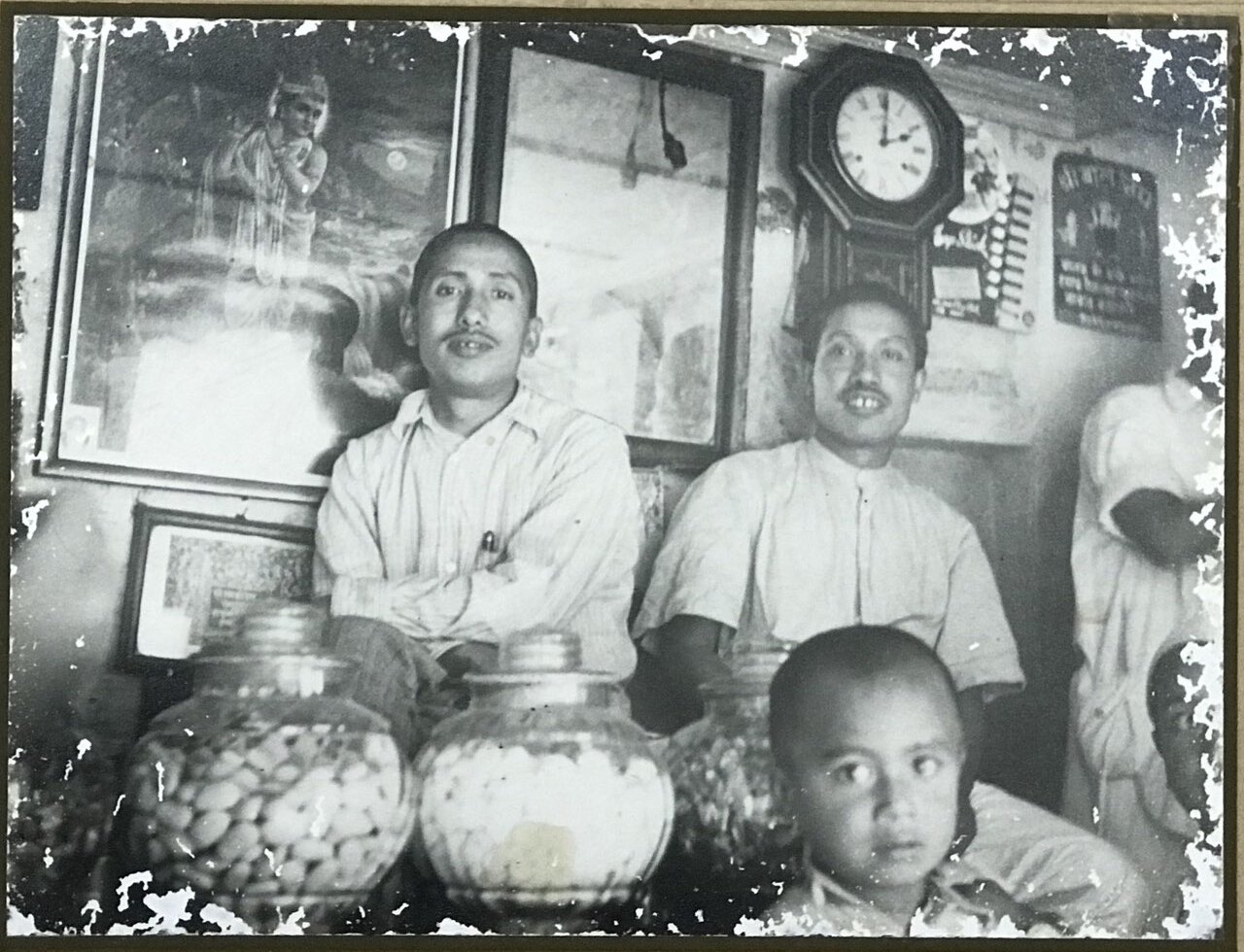

Every morning as a boy, Shreedhar Lal Manandhar made sure that he did not miss the chance of drinking tea at Tilauri Mailako Pasal, a tea shop owned by two brothers right by the Dharahara tower.

“My father started his day by taking a bath at the stone spouts at Sundhara, and then he'd sit at Tilauri Mailako Pasal to drink tea,” recalled the 81-year-old veteran photographer. “My brother and I made sure we didn’t miss accompanying him as we loved drinking tea at Tilauri Mailako Pasal.”

Like Manandhar's father, many others from the neighbourhoods of Khichapokhari, New Road and Asan also headed from the spouts to the shop, asking for tea, which the brothers had only recently introduced to their shop. Manandhar, as well as the brothers' family members, recall that all through the day, customers stopped for this drink--in the afternoons students from Durbar High School, Teendhara Pathshala, and Tri-Chandra Campus and government workers at the nearby Hanuman Dhoka and, in the evenings, soldiers after their evening parades at Tundikhel.

It was the 1940s and, like Tilauri Mailako Pasal, a few tea shops had come to dot Kathmandu localities. Taste buds accustomed to waking up to milk, hookah smoke or even shots of home-brewed aila, were now seeking sips of tea at these tea shops right from the break of the dawn. Indeed, it was these early tea shops that would introduce and popularise tea to the taste buds of Kathmandu's commoners.

But by the time these tea shops even appeared in Kathmandu, the Rana and Shah durbars were most likely already brewing tea in the proper English style way back in the 1800s during the reign of Rana Prime Minister Jung Bahadur. Kathmandu’s small privileged class--families close to the Ranas and Shahs, and business and migrant families--were also already drinking tea at their homes by the 1930s at the latest.

Foundations of Kathmandu’s tea culture were laid in the period stretching nearly from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s. During this period, popular British tea brands arrived from faraway lands, and tea was brewed the British way before the method of boiling tea, water, milk and sugar altogether came to exist alongside. Tea as a novel drink had everything to instantly appeal to Kathmandu’s sense of new and fascination.

Hodgson's tea plants, Ranas' teapots

The tale of Kathmandu’s tea connects most likely to the early 19th century after the opening of British residency here in 1816, and the earliest documented accounts of tea in the Valley trace to the first two British residents.

In his book ‘The Tale of Tea’, Professor of Linguist George van Driem mentions that in September 1818, Kathmandu’s first British resident Edward Gardner reported a tea tree growing in a private garden in Kathmandu. Later, writes van Driem, Danish botanist Nathaniel Wallich witnessed the same tea tree during his sojourn in Kathmandu in 1820-21.

Meanwhile, Gardner's successor Brian Hodgson, who lived in Kathmandu from 1820 to 1843 (as a British resident from 1833-1843), went on to grow his own tea plants in the residency garden as part of his study on the suitability of the Valley's climate for growing tea.

"[T]ea-growing was fully ascertained twenty-five years ago in the valley of Nepal," Hodgson wrote in his 1856 essay ‘On the colonization of the Himalaya by European’. "Tea seeds and plants were procured from China through the medium of Cashmere [sic] merchants then located at Kathmandu. They were sown and planted in the residency garden, where they flourished greatly."

Although not directly related to the acts of drinking tea, these accounts accord value because the opening of the residency meant that Kathmandu Valley now had a household where tea was not only an everyday culture but that its residents took interest in tea. And, it is to the direct interactions of the residents and other residency officials with Kathmandu's rulers that we can possibly trace Kathmandu's encounter with tea culture to.

Aside from the interactions with the British residents, when Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana visited England in 1850, he must certainly have been exposed to tea culture in the many official engagements he had with the British royalty and aristocrats, although tea does not appear in his travelogue ‘Jung Bahadurko Belayit Yatra’. In Nepal itself, Jung Bahadur-and indeed all his successors--regularly interacted with the British, including during hunting expeditions in Nepal’s plains with British royalties, which most possibly exposed the Ranas, Shahs and other high officials to the British tea culture.

It was during Jung Bahadur’s reign itself, in 1873, that his son-in-law, Colonel Gajaraj Singh Thapa, who was then the governor-general of the eastern region, established Nepal’s first tea plantations in Illam. Signposts placed in these plantations today state that the tea saplings planted by Thapa were received as a gift from the Government of China to Jung Bahadur himself. But, here too, it is not clear whether tea grown in these plantations was consumed in Kathmandu’s durbars.

There does exist more concrete evidence telling that the ruling families were drinking tea by the mid-19th century at the latest. English traveller Francis Egerton, who travelled to Kathmandu in the early 1850s during Jung Bahadur's reign, refers to a shop retailing British goods shipped all the way from Britain for sale in Kathmandu for the ruling and upper classes in his 1852 book ‘Journal of a Winter’s Tour in India V2: With a Visit to the Court Of Nepaul’. According to him, among the items displayed in the shop were teapots.

But does it mean that tea was common among the Ranas and Shahs?

In a lack of published accounts on tea culture in Shah and Rana households, what oral history suggests is that tea was not as common in all Rana households, although they were clearly among Kathmandu’s tiny group that could import foreign goods including tea. Rather, it was still a new or was a luxury drink to at least a portion of Rana households even until a good part of the early decades of the 20th century.

Purusottam SJB Rana, 96, was born in Bahadur Bhawan, where the Election Commission sits today, and he spent the first nine years of his life there before his grandfather General Rudra Shumsher was stripped from the roll of succession to the post of Rana Prime Minister and sent off to Palpa as its governor-general during the reign of Juddha Shumsher in 1934.

“There was no culture of drinking tea at Bahadur Bhawan. The first time I had tea was when I was around 11-12 years old, and it was in Palpa. It was during Panchak [Tihar], while gambling (playing juwa) during nighttime that my father [and others] would drink tea in beautiful, emblazoned China cups, whose designs I really found attractive," said Purusottam.

Ratna Shumsher Rana, the former Vice-Chairperson of the National Planning Commission, whose grandfather Dhana Shumsher was the governor-general of Pokhara in the 1940s, recalls that as a small boy in the 1940s, tea was a luxury drink offered only when guests came.

“There'd be guests over, both foreign guests as well as officials from Kathmandu. I remember tea was served on such occasions," said the 82-year-old. "I drank tea for the first time at one such moment. Except for these special occasions, there was no tradition of regularly drinking tea at our house.

"We started drinking tea regularly at home only after shifting to Kathmandu after the Rana regime ended (in 1951). Otherwise, we had the culture of drinking milk,” said Ratna.

The late novelist Diamond Shumsher Rana, had recalled when he was 92, in an article ‘Chiya Bhitriyeko Katha’ by journalist Jayadev Bhattarai in the monthly magazine Yubamanch that his first encounter with tea happened on seeing members of the Rana clan--Daman Shumsher, Khem Shumsher and Som Shumsher--drinking tea in the 1920s after returning to Kathmandu from their studies in Allahabad in India.

But, it would be the 1940s before Diamond Shumsher had his first cup of tea at Tilauri Mailako Pasal. This was also the time when tea culture was gradually seeping broadly into the houses of commoners.

Kathmandu's privileged class drinks tea

Before tea was known to Kathmandu’s broader population of commoners, tea was affordable only to its tiny privileged class. Learning from the rulers, families close to the Ranas and Shahs would gain tea habits early on, as would Kathmandu’s trading and business class and migrant families, who brought tea culture to Kathmandu after getting exposed to the drink abroad.

Kashinath Acharya Dixit, famous as Maila Pandit, and a trusted official of the Ranas and Shahs was apparently introduced to tea in the royal palace.

"Kashinath Dixit was introduced to tea when he shared a dining table with King Prithivi Bir Bikram Shah," said a source in Kathmandu's Dixit family who wishes to remain anonymous. "In his family, the elder family members drank first and then the other younger members, just as they ate meals in those times."

Historian Mahesh Raj Pant, 77, also shares how his mother's family drank tea due to their association with the royals. Pant's mother, Budhakumari, was the daughter of royal priest Janakraj Pandey, who was dear to the Rana Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher.

"My mother was the daughter of a royal priest. She drank tea, but oddly enough, nobody else in my family drank it," he said. "She must have become habituated to tea when she was a girl, and so she could not leave it after coming to her husband's home. She drank from a large silver glass. When I was a boy, sometimes I did drink leftovers from her glass out of curiosity, but otherwise, I did not drink tea. Instead, I would drink milk early in the morning."

Given that Prithivi Bir Bikram Shah died in 1911, and Pant’s mother was born in 1914, these anecdotes trace perhaps to some early non-royal families having tea at their homes. Otherwise, even until the 1930s or 1940s, only a small portion of the upper class, migrants to Kathmandu, and business people (like the community of Kathmandu’s Lhasa Newa merchants) had tea at home.

For centuries, Kathmandu’s Lhasa Newa merchants traversed the mountains to Lhasa, conducting trade between Nepal, Tibet and Bengal (India) with business houses located in Calcutta and Lhasa. They were often among the first Kathmandu denizens to come in contact with foreign inventions and goods, and naturally also food culture. And so, they were also among the early groups in Kathmandu to be exposed to and adopt Western tea culture.

Kamal Ratna Tuladhar’s father was among the last generation of traditional Lhasa Newa merchants who travelled to and lived in Tibet before returning from the last of his three trips in 1954.

“I think the tea-drinking culture among Lhasa Newa merchants came from Calcutta where many maintained business offices,” said the 65-year-old author of ‘Caravan to Lhasa: A Merchant of Kathmandu in Traditional Tibet’.

His own family has been drinking tea since his grandfather’s time in the 1930s, and he explained that the families of Lhasa merchants adopted Western tea alongside Tibetan tea.

“Tea was common in the homes of the merchants and many drank it in the morning and afternoon,” he said. “But among Lhasa Newa families, it was usual to have Tibetan tea in the morning and Western-style tea in the afternoon. [...] This tradition lasted till the 1960s in our family. Other families drank Western-style tea in the morning.”

The family of Thakur Lal Manandhar, a scholar of culture, and from a family of grocery and food suppliers to the Rana durbars also started having tea in the 1930s. Manandhar's son Shreedhar Lal Manandhar claims his family’s connection to tea to a rather remarkable character.

“It was after meeting Shivapuri Baba that my father started having tea at our house,” said Shreedhar Lal. “My father also supported him and started importing tea for Baba, and in the process, we also started getting supplies for us as well.”

A noted saint, Shivapuri Baba lived in Kathmandu from 1925 until his death in 1963, dividing his time between his ashrams at the top of Shivapuri Hill and Dhrubasthali near Pashupatinath Temple. The saint, whose love of tea was well known to his followers, was apparently having tea in his ashram by the early 1930s at the latest.

"[Shivapuri Baba instructed] Madhav's father, who voluntarily worked for him, to offer me a cup of tea daily, when I arrive," recounts Thakur Lal in YB Shrestha Malla's book ‘Right Living: The Teaching of Shri Shivapuri Baba’ of his first meeting with the saint in 1932.

Originally from southern India, Shivapuri Baba had for long enjoyed drinking tea. Like him, Indian families settling in Kathmandu were another group to have tea at home. Among them was Sardar Manohar Singh, who migrated to Kathmandu in 1931 from Rawalpindi in the then British India after being hired as a Nepal government overseer. Someone used to having multiple cups of tea daily back home, tea certainly was one of the things that Singh dearly missed when he first arrived in Kathmandu, recalled his daughter-in-law Jagdish Kaur.

"But soon in his home [in Kathmandu], he would start having tea," 72-year-old Kaur said. "He got his tea supplies from India whenever he visited back home, and one of the most cherished items his relatives brought from India was tea.”

Those migrating to Kathmandu from the distant districts bordering India were also drinking tea in their houses as early as the 1930s, like the family of Murlidhar Uprety, who was originally from Dadeldhura district and was a senior government official and tuition teacher to the Rana families. Arbind Rimal, who was a classmate to Uprety's son Chandradhar Uprety, recounts how he was attracted to drinking tea at the latter's house when they took tuition lessons with the Uprety brothers in the late 1930s.

"They drank tea at Channu's [Chandradhar] house because his ancestors had come from Doti-Dadeldhura," he writes in his book ‘1997 Saal Dekhi 2007 Saal samma: Ek Awalokan’.

Via tea shops, tea seeps deeper

Beyond the royals and Kathmandu's tiny privileged class, it was tea shops that would introduce tea to Kathmandu's commoners.

As a regular visitor to Tilauri Mailako Pasal, Shreedhar Lal saw how this tea shop introduced its early customers to tea.

“Most of those who came to Tilauri Mailako Pasal drank tea for the first time at the shop,” he said. “They drank tea at the shop because they wouldn’t have that in their homes, as there was no tradition of tea back then. Only a few rich families drank tea at their homes.”

Oral accounts commonly related by Kathmandu's elderly attribute the Valley’s tea culture to soldiers returning from the Second World War. This account also links tea at Tilauri Mailako Pasal to the returning soldiers. Writer Janak Lal Sharma notes in his article ‘Channu Uprety: Ek Jhajhalko’ compiled in Chandradhar Uprety Smriti-Grantha that Tilauri Mailako Pasal started selling tea ‘to serve tea to soldiers who had returned from the Second World War.’

Whatever the exact relationship between soldiers and Kathmandu’s tea shops, a small number of tea shops like Tilauri Mailako Pasal were dotting Kathmandu localities in the 1940s and bringing the taste of tea to Kathmandu's commoners.

Tilauri Mailako Pasal was selling tea by 1945 at the latest, as recounted by Jog Narayan Dangol, one of the two brothers operating it, in ‘Right Living’. Opened around 1948, another known place selling tea was Laptanko Hotel in Dillibazar that was opened by a retired second lieutenant of Nepal Army. This tea shop is a subject of Rimal’s essay ‘Dillibazarko Laptanko Hotel’.

Meanwhile, in Kamalpokhari, Krishna Bahadur Rajkarnikar, the founder of Krishna Pauroti that pioneered Western style bread in Nepal, added tea on the menu in his halwai shop.

"We started selling tea in our halwai shop in Kamalpokhari right after we founded Krishna Pauroti in 1948," said Rajkarnikar's son, writer Ghanashyam Rajkarnikar, 80.

New Hotel in New Road was another tea shop that finds mention in memoirs and memories. There was also the popular Masterchako Pasal near Durbar High School that fondly appears in memoirs and memoir essays of its alma mater.

In these early years, a glass of tea cost several paisas. The shops also made tea affordable for customers by offering half glass tea at a lesser price. At one point, Laptanko Hotel sold a glass and half glass tea at 10 and 5 paisa, respectively, writes Rimal in his essay.

Like Diamond Shumsher Rana, who states in the Yubamanch article that he had his first cup of tea in Tilauri Mailako Pasal, many Kathmandu denizens had tea for the first time in their lives in these tea shops. Veteran journalist Bhairab Risal, 94, also recalls in his memoir ‘Sushila-Bhairab’ that he drank tea for the first time at Tilauri Mailako Pasal in 1948. Ninety-four-year-old Goraksha Bahadur Nuchhe Pradhan, a former secretary of government of Nepal, meanwhile recalled having his first drink of tea at Masterchako Pasal in 1948.

While many details of these early tea shops remain hazy, what is clear is that by the late 1940s, tea’s popularity among Kathmandu commoners was soaring, something more firmly attested to by a government notice published on November 25, 1949 issue of Gorkhapatra. The notice, calling for tender to open shops in the premises of the newly opened Kathmandu's first cinema hall in New Road, states that in the shop, various items including ‘milk tea can be sold at a price not more than market price.’

From faraway lands and fascinations

Where did Kathmandu get its tea from? How did it prepare its tea? And how did Kathmandu denizens respond to this novel drink? For the Valley that was largely insulated from the outside world and experiences, these questions beg to be answered.

Kathmandu was drinking famous British tea brands such as Brooke Bond and Lipton manufactured as far away as Ceylon--the present-day Sri Lanka. Calcutta being the political and commercial capital of British India, and the travel destination of Kathmandu’s royals, elites, and work station of its Lhasa merchants, tea supplies to the Valley mostly came from this Indian city.

"Families [close to the royals] had access to Calcutta and that's where they got their tea from,” said the source in the Dixit family. “They got their supplies when tea was imported to the durbars from Calcutta or when they themselves travelled to the city."

Tuladhar said that Kathmandu’s traders too procured their tea supplies from Calcutta, and that Brooke Bond and Lipton were popular brands.

“Since the traders went to Calcutta frequently, they brought tea from there,” he said.

Darjeeling and Benaras also supplied tea to Kathmandu. R P Singh, a compounder from New Road, known by the alias Gore Dai Compounder, and a devotee of Shivapuri Baba, apparently imported tea for the saint from Darjeeling after meeting him in 1941. "Finding that [Shivapuri Baba] did not like the usual stuff, I imported tea from Darjeeling, the best tea then being Lepcha tea,” he recounts in ‘Right Living’.

Later on, Gore Dai would help Thakur Lal import tea for Shivapuri Baba, claimed Shreedhar Lal.

"For Shivapuri Baba, my father ordered the tea he liked from India," he said. "He liked the Lipton Green Label, the one that came in tins, not paper boxes. […] Gore Dai Compounder ordered for us. Because he worked on pharmaceuticals, he knew how to import."

Gore Dai indeed also appeared to have procured tea for Tilauri Mailako Pasal. The tea that he brought for Shivapuri Baba, he also supplied to Tilauri Maila. "Most of it, I managed to sell through Kancha Dai…who had a small tea shop at the [Dharahara] tower," he says in ‘Right Living’.

Physically arriving from faraway cities, tea was also prepared in just the same manner that the British and Europeans did. The British traditionally prepare tea using two methods. One, they put tea leaves on a tea infuser or strainer and place it inside the teapot or cup, pour hot water and cover the teapot or cup to bring colour. Two, they pour hot water over tea leaves inside a teapot. In both these methods, milk and sugar are added on cups themselves according to taste.

Describing the British methods of brewing tea, Ratna Shumsher Rana recalled that tea was brewed the British way in the homes of the Shahs, Ranas and other early tea drinkers.

“After all, we learnt tea culture from them [the British]," he said.

This tradition passed on to the families who learnt to drink tea from the royals.

"Kashinath Dixit’s family learnt to prepare tea in the same manner that the royal families learnt from the British,” the Dixit family source said. “That is, they first brewed tea and then added a little milk later. Also, they drank in a teacup.”

With time, today’s more common method of boiling water and milk together with tea and sugar came to the scene of Kathmandu’s budding tea culture alongside the English method of brewing tea.

“Tea [was] made the usual way-boiling tea leaves and adding milk and sugar into the kettle while the water is still boiling,” said Tuladhar on how tea was prepared in his home.

Tilauri Mailako Pasal too used this method at first. According to family members, later at one point, they adopted a unique method of boiling black tea and milk separately. They’d be mixed in a tumbler along with a teaspoon of sugar just before serving.

The novel drink from foreign lands would instantly capture the imaginations of early drinkers, evoking a sense of mystery and fascinations that find expressions in tea experiences recollected in memoirs and elderly’s memories.

"Along with getting teacher's loving lessons, what also attracted me was a mysterious bliss of drinking tea," Rimal expresses his tea experience in ‘1997 Saal Dekhi 2007 Saal samma: Ek Awalokan’.

Shreedhar Lal’s cousins shared similar enthusiasm to visit the former's house because there, unlike in their home, they could drink tea.

"My cousins named my mother Chiya Bajai because they could have tea in our home. She’d prepare tea for all immediately after they came," he said. "If we had guests over, we entertained them with tea, especially when the cousins came."

Diamond Shumsher has recalled in the Yubamanch article how he would wonder what this drink called tea was and be amused to see Som Shumsher, Daman Shumsher and Khem Shumsher saying "Chiya piune chiya" and sipping from their cup.

For this generation of early tea drinkers, the early amusement and attraction would pave way to craving and eventually accustom them to the habit of tea, the process perhaps best captured in Risal's recollection of his experience of drinking tea at Tilauri Mailako Pasal.

"Somehow, without knowing, I had become habituated to drinking tea," he writes in his memoir. "Sipping hot tea with khatyouri [a confectionary made out of molasses] was delightful. My mouth would burn while drinking the hot tea. My tongue was not yet accustomed to the way of drinking tea. I’d take the glass and sip tea by cooling it with my breath and making a slurping sound."

In the 1940s, just like Risal, many Kathmandu citizens were becoming accustomed to this new habit at the city’s tea shops. But not all Kathmandu folks could freely cherish this early tea experience; doors of tea shops were partially closed or even tightly shut for ‘lower’ castes.

Poet Ramesh Khakurel, 79, was born in Khichapokhari. One childhood memory he has is of a small tea stall operating out of a falchha in Ranamukteshwor near his house in the late 1940s. "On a board somewhere on the top of the stall was written in Devanagiri letters Paani nachalne banda [Untouchables not allowed]," he said.

Khakurel explained that in such a deeply caste-conscious society, it was entirely the prerogative of the owners of any eateries whether or not to entertain those considered as 'lower' castes.

And those who did allow took precautionary measures.

“They didn’t allow lower caste entry into the shop and served them outside,” said Manandhar of Tilauri Mailako Pasal.

"Lower castes had to bring their own glasses," he added. "Those who drank in the shop’s glasses had to wash them after drinking.”

Dawn of democracy with the end of the Rana regime in 1951 did little to immediately change the age-old oppression of the ‘lower’ caste. And it would be several more decades before the ‘lower’ castes were allowed to freely access teashops or eateries.

But in Kathmandu’s imagination and memory, the advent of democracy would signify a marker separating the periods with and without tea culture. Kathmandu’s elderly almost unanimously echo “Chiya khane chalan saat saal pachi matra ako ho”, meaning, in essence, that tea culture would become widespread and an inseparable part of Kathmandu’s food culture only after 1951.

Kathmandu's elderly also say that in the decades of the 50s and 60s, the number of tea shops increased. Tea would also spread its reach into commoners’ kitchens. And, in these decades, tea that was already brewed in Kathmandu’s durbars in the 1800s would eventually come to become an intrinsic part of Kathmandu's everyday life.

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu