Culture & Lifestyle

‘Nepal has the potential to pursue world-class research and design’

Anwit Adhikari on his passion for design and technology, underscoring both the barriers and the scope within the Nepali education system for engineers.

Pasang Dorjee

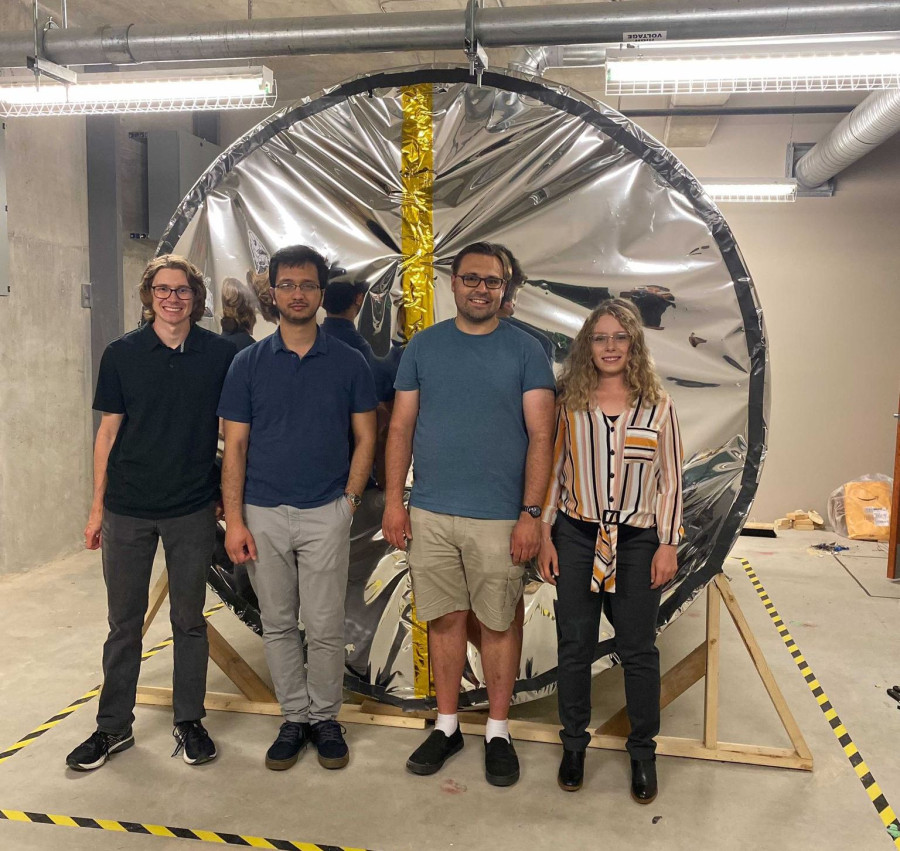

Mankind’s quest to inhabit Mars is becoming less fictitious and nearing execution with the advent of technology each year. For this dream to materialise, scientists, researchers, and engineers have been striving relentlessly to build cutting edge tools required to visit the red planet in the near future. One such element crucial for this process is an airlock, which acts as a bridge between the atmosphere of our planet and Mars. Celestial Labs, a team from the University of Regina in Canada, have created the aforementioned Martian airlock prototype—adding one more piece to the puzzle. Hailing all the way from Palpa, Nepal, Anwit Adhikari is the division head of Celestial Labs. Adhikari exemplifies what Nepali engineers are capable of, when moulded by tenacity, the right resources, and a healthy support system.

In conversation with the Post’s Pasang Dorjee, the Canada-based mechanical engineer/entrepreneur details his intense fervour for design and technology—and how his university team built the airlock prototype for the purpose of allowing humans to visit Mars in the future.

Could you define what an airlock is in layman’s terms?

An airlock is a small room attached to the outside of an extraterrestrial habitat that prevents the human-friendly atmosphere inside from leaking out into the hostile environment of space or Mars. It acts as a bridge between the atmosphere on Mars and the Earth-like atmosphere needed in space for people to breathe. It allows astronauts on Mars to walk on one side of the structure, wait for the pressure to adjust, and then walk out the other side.

What led to the conception of this airlock?

The Martian airlock came out of a nationwide competition organised by the Mars Colony Team at the University of British Columbia back in 2018, whose goal was to see which Canadian university could design and build the best airlock system to be used on Mars. The competition was divided into two phases: the design phase in May 2019, and the prototype phase in August 2021. The airlock that our team had a role in designing bagged the first prize in both. The team at Celestial Labs was divided into multiple smaller, self-motivated teams that pursued their objectives in parallel. I was leading the team that designed the structural and ventilation systems for the airlock, while other teams handled radiation, insulation, and electronic systems, along with logistics and finances for manufacturing. Since no major aerospace firm has (at least publicly) worked on a Martian airlock, our team is hoping that some of our design solutions could be used in a real Martian airlock someday.

What have been some of the challenges faced by your team while building this airlock?

Given that Mars is a novel environment, everything had to be designed from scratch. Considering Mars’ temperature and radiation, using metal presented difficulties so we had to find a new polymer that could perform well under those circumstances. Making everything modular enough that it could be 3D printed on Mars was challenging. We had to be creative in creating a structure that could handle the stress loads but could also be folded neatly into a compact volume and transported to Mars. In the division that I led, there were almost 100 major design iterations over the course of the last two years alone.

It seems that you have been involved with start-ups since 17, which could mean that your passion for engineering is not something completely moulded by the limited options in the Nepali educational curriculum but rather out of personal interest? Would you say so?

I have been interested in technology since I was six. I could not see how the options provided by the Nepali education system could foster my interest in design, so I pursued it independently. I have also always been fascinated by the beauty in design, and aircraft and spacecraft represent the highest form of design and problem solving that there is for me. As a child, I would spend hours looking at aircraft, and I knew I wanted to be the person who designed them.

I tried my hand at multiple projects when I was a kid, including a compressed air-piston engine and a telescope. They all failed, but they reinforced my belief that I should pursue R&D as my career, and so I took a major leap when I was 17 and started working on my own research project. Growing up in Kathmandu, I remember visiting the British Council library to read materials related to physics and would scour through the shelves of Mandala Book Point to devour books that catered to my interests. After finishing Grade 10 from Triyog Higher Secondary School, I went on to complete my A levels from Rato Bangala School in 2010. In the subsequent years, I paused my education to further cultivate my interests and travelled to Silicon Valley to network with entrepreneurs and study the start-up culture. I eventually decided to pursue my undergraduate in Physics at the University of Regina in 2015 and completed it in 2020.

Who have been the strongest influences in your life?

That has always been my parents first and foremost, who, through our routine trips to my home village in Palpa, made me understand how fortunate I was in being able to have a middle-class upbringing in the capital. I understood that not every Nepali child had that privilege, and I was careful to not take it for granted.

I was always fascinated by Sergei Korolev, the Russian rocket engineer who pioneered many firsts in the space industry, ranging from Sputnik, the first satellite in space, to Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space. Sergei Korolev’s rocket system, the Soyuz, is still in use today more than 60 years later. I’ve also been inspired by Kelly Johnson, the American aerospace engineer who led the design of the SR-71 Blackbird—the iconic 1962 spy plane that could travel faster than a bullet and was so fast it evaded every enemy missile that was shot at it in its 30 years of service.

How did you come across Celestial Labs? Tell us about your journey as the division head of the company.

Before coming to Celestial Labs, I was working on my research on the side, focusing on solar energy. I was introduced to the project head of Celestial Labs by a mutual friend who knew about my interest in start-ups and technology. I essentially picked the systems that no one else was working on at that time, and once the team lead had trust in my ability to follow through with these problems, I was made the team lead for my division.

In relation to your endeavour in engineering, do you see yourself doing something in Nepal?

I do believe Nepal has the potential to pursue world-class research and design in multiple advanced technical fields, and I would be happy to contribute to that in the future. As of now, I am focused on establishing my experience and credibility in my own field before I decide to return to my hometown.

What do you suggest could be done to foster an environment in our country that is conducive for future generations of aspiring engineers and physics enthusiasts?

Nepalis have a risk-averse mindset when it comes to pursuing entrepreneurship and technological innovation, and that cannot change unless we have a national dialogue on how crucial innovation is to our economy and national pride. We have to be comfortable with our youth engaging in projects they care about, even if they fail. I have witnessed world-class teams led by former NASA interns and nuclear physicists fail, and that is a part of the learning process, but this is a difficult concept to absorb in our culture that does not tolerate career failure.

What do you think your representation in the field of physics could mean for the larger Nepali community?

It means that it is possible for an average Nepali citizen to accomplish something they find meaningful, given the opportunity. Even the best teams at the design rooms of SpaceX and NASA are ultimately just a group of people who pursued what they found meaningful. Although it may seem daunting from the outside, I still see absolutely no reason why the Nepali community cannot replicate that.

22.65°C Kathmandu

22.65°C Kathmandu