Culture & Lifestyle

Portraits from the Tibetan diaspora

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee’s first solo exhibition, ‘I Shouldn’t Be Here’, brings colourful and intimate personal portraits of the experiences of the Tibetan refugees.

Srizu Bajracharya & Tsering Ngodup Lama

In the few years that Lalitpur’s Windhorse Gallery has been operational, it has earned a reputation for providing little-known artists from Himalayan communities its space to showcase their works. The most recent artist to exhibit works at the gallery is Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee, a second-generation Tibetan refugee based in India. Since May 27, the gallery has been exhibiting Dorjee’s 'I Shouldn't Be Here', which features intimate personal portraits of the Tibetan diaspora.

Some of the factors that make Dorjee's artworks unique are the material used and his art-making process. In many of the exhibition’s artworks, Dorjee uses Drochak-bhureh (tarp sacks) as a canvas. The decision to use sacks echoes the Tibetan diaspora’s experience of resettlement. In the early years of life in exile, relief materials to the Tibetan communities in India and Nepal came packed in tarp sacks. His art-making process is meticulous and meditative and is different from how artists usually fill colours in their works. In many of his works, Dorjee transfers colours to his canvas instead of applying paint directly.

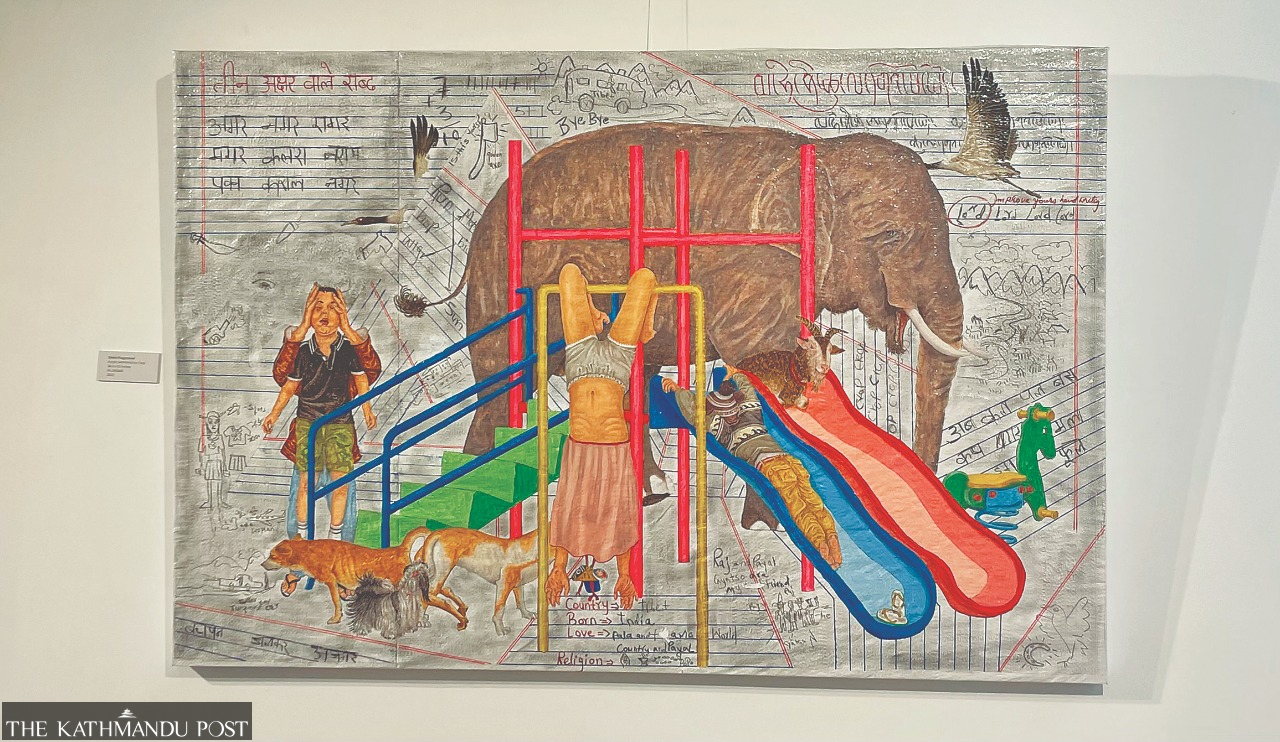

The first painting that greets visitors is the ‘Silent Playground’, which unfolds on top of a collage of notebook papers belonging to a student from a Tibetan school. As the name suggests, the artwork depicts a scene of children playing in a playground. If one observes the artwork carefully, one can almost hear crackles of laughter ringing in the air. The painting also has a lot of small details that lend the artwork a touch of Tibetan-ness. In the middle of the painting is a playful little girl wearing a photo of the Dalai Lama around her neck, a common practice among Tibetan Buddhists to show their devotion to their spiritual leader. A little above the playful girl is a childish drawing of an oddly-shaped bus with the word Tibet written across it, perhaps symbolising that the bus is heading to Tibet. At the bottom end of the artwork are answers written by a Tibetan kid to questions about his country, origin, love, and religion. In his childish handwriting, the boy responds as honestly as he can—he identifies Tibet as his country of origin but his birth country as India. For love, he writes down a long list that includes pala (which translates to father in Tibetan), amala (mother in Tibetan), world, country, and Payal, his Indian friend. At the bottom left corner of the painting are childish drawings of what is supposed to be a gold aeroplane and a turquoise car, both of which are mentioned in a popular Tibetan song that pays tribute to the Dalai Lama.

The exhibition features several such artworks that allow viewers to go on a heartwarming (oftentimes heartaching) journey to see what life is like for Tibetan refugees and the nuances of their struggles in attempting to find some semblance of normal life far from their country Tibet. But Dorjee’s works are not fishing for sympathy for the Tibetans. Instead, it wants viewers to see the Tibetan community’s resilience and humility and the great lengths they have gone to adapt to a life in exile and keep their cultures and traditions alive.

While India may be home to the largest Tibetan diaspora, Nepal’s Tibetan refugees make up the country’s largest refugee community. Nepal has been hosting Tibetan refugees since the late 1950s, and it is estimated more than 15,000 Tibetan refugees continue to live in the country. This is why exhibiting ‘I Shouldn’t Be Here’ in Nepal makes sense because it serves as a window for Nepalis to better understand what life is like for Nepal’s Tibetan diaspora.

“Most of these works are part of my memories. I wanted to celebrate how the Tibetan diaspora has held intact our resilience and humility even after all these years since leaving Tibet,” says Dorjee on a recent afternoon at the gallery.

Even though the artworks might be deeply personal to Dorjee, some of the subject matters they explore are familiar and universal.

One such universal artwork is ‘Mood Swing’. The work is set inside a bathroom and features Dorjee’s sister wearing costumes of DC and Disney characters. The painting shows his sister making comical facial expressions and just being herself and confronting her moods. The artwork delves into the ‘identity’ we all try to make for ourselves in a world that keeps demanding that we be something else. Dorjee says that the idea for the artwork came to him while trying to cheer his sister after she lost her job.

“I made this painting to make my sister smile and convince her not to worry too much about what the world might think about her. I wanted her to keep her child-like nature intact and not be too hard on herself,” he says.

In his artwork titled ‘The Sky is Falling’, the central character is his father, and the work is Dorjee’s attempt to explore the importance his father places on compassion. The painting shows Dorjee’s father chasing away a cat that is only doing what is natural to him: trying to kill a bird.

“My father is a very compassionate person. He can’t bear the sight of any living being suffering and is always trying to save everyone, which I don’t think is humanly possible,” says Dorjee.

There are a few other paintings in the exhibition that explore such universal themes, but the subject of the majority of the artworks in the exhibition revolves around the experiences of the Tibetan diaspora. His artwork titled ‘Champions’ wanders into that very subject and does so in a way that makes it the most moving piece in the exhibition.

The artwork features a Tibetan-Indian athlete standing on a podium and raising the Indian flag to mark her victory, perhaps in a national competition. Instead of being surrounded by audiences cheering for her victory, she is alone and enclosed by a wall, and you can almost hear the heart-aching silence lingering in the air.

Dorjee explains that the artwork was inspired by the experiences of Tibetan-Indian wushu and a mixed martial arts athlete who has represented India in international martial arts competitions.

“Circumstances have forced many Tibetans in India to take up Indian citizenship. A few of them have even represented India on international platforms and made their adopted country proud, but despite their achievements, they are still considered outsiders and do not get the same recognition,” says Dorjee.

Born and raised in India’s Himachal Pradesh, Dorjee, like many Tibetan refugee children in India, attended a Tibetan community school. Dorjee says that he developed an appreciation for art very early on in life.

“My father often makes free-hand sketches, and he is very good at it. As a young boy, I would make sketches as well. As far as I can remember, I have always been this person who enjoyed creating art and collecting them,” says Dorjee.

But it was much later in life that Dorjee decided to become a full-time artist. After graduating from high school, he had his mind set on becoming a genetic engineer. When he failed to get into his desired genetic engineering college, his sister suggested that he take a gap year and try getting into the college the following year.

During this gap year, Dorjee started drawing again and fell in love with the process. The following year, he joined College of Art, Delhi and graduated in 2012. For the next few years, the artworks Dorjee made dealt with darker stylistics.

“It took me a few years to realise that people don’t want to spend their hard-earned money on artworks that dealt with dark subject matters,” says Dorjee. “To sustain myself financially, I started making digital art.”

But the journey to becoming the artist that Dorjee has become today started when he met Nepali contemporary artist Ang Tsherin Sherpa in 2017. His interaction with Sherpa, says Dorjee, changed how he looked at art.

“When I met Ang Tsherin-la for the first time, I had just graduated from art school. When I met him again in 2017, I was on the verge of giving up art for good. During that meeting, he bought one of my paintings, and something within me shifted,” says Dorjee. “You see, it was the first time someone had truly valued my work. And that was enough for me to rethink my decision to give up art. I will forever be grateful to him for having faith in me.”

Sherpa still remembers the reserved Dorjee who assisted him during a residency programme in 2012.

“To be honest, I didn’t really like his works at first. They felt dark, and maybe it was because he was in that space at the time,” shares Sherpa in a phone interview.

But through the years, Sherpa says that Dorjee has grown as an artist and become more committed to the idea of becoming an artist.

“With this exhibition, he brings to the audience stories from the Tibetan diaspora that we rarely see represented in art. And his work feels universal as we all are moving around so much. We all can relate to the diaspora experience,” Sherpa tells the Post.

The exhibition, says Dorjee, has made him realise the important role art can play in telling stories and highlighting issues.

“I have interacted with a few local Tibetans here at the gallery, and they have thanked me for making them feel seen and heard. It also surprised me that many Nepali art lovers that I have met here at the gallery told me that they had no idea that Tibetan refugees even exist in Nepal,” says Dorjee. “It is beginning to dawn on me my responsibility as an artist to serve my community, and I am really looking forward to the journey ahead.”

‘I Shouldn’t Be Here’ is on display until June 30 at Wind Horse Gallery, Bhanimandal, Lalitpur.

22.65°C Kathmandu

22.65°C Kathmandu