Culture & Lifestyle

Fighting with Asan’s bulls: The legend of Sancha Pahalman of Thahiti

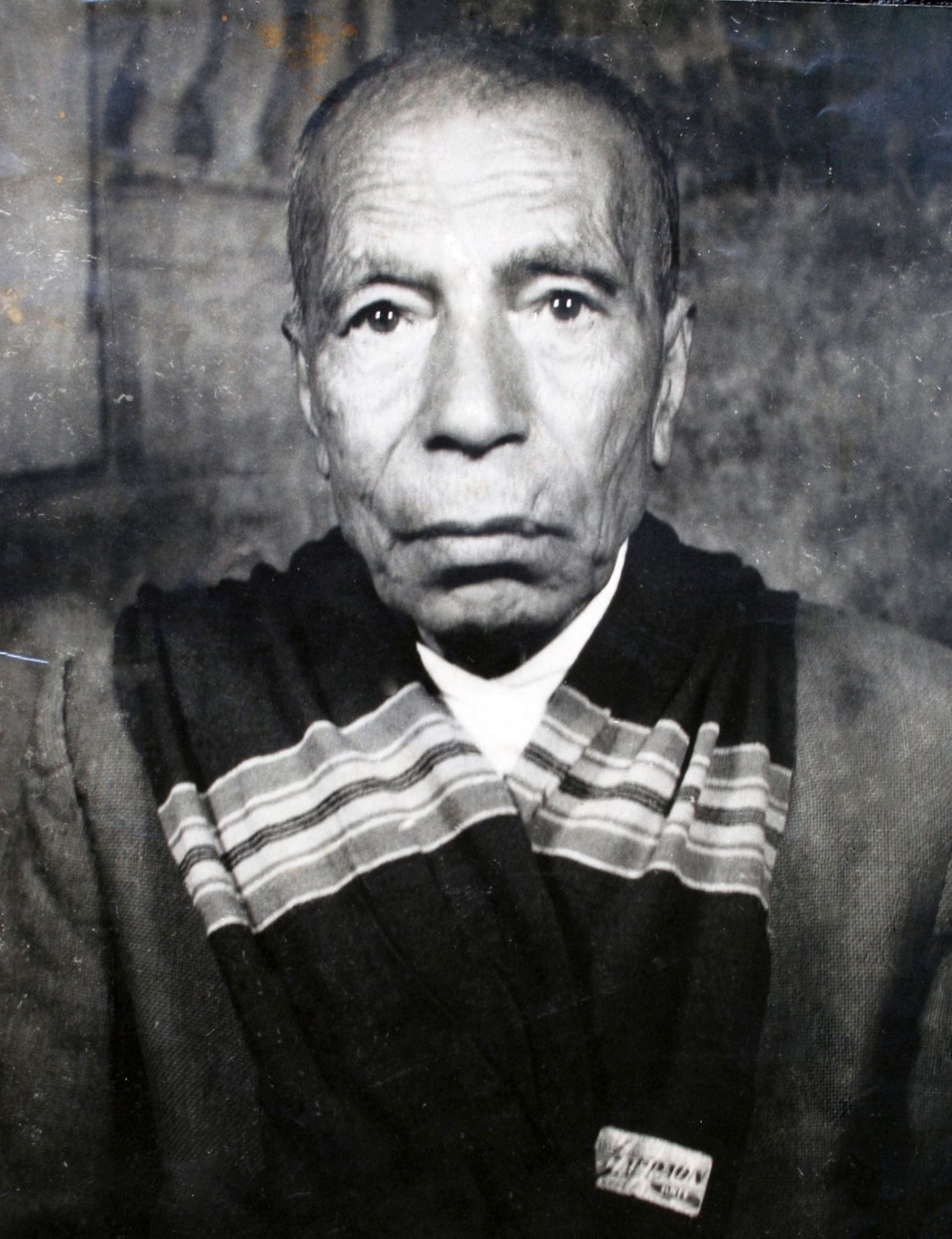

The famed and notorious strongman who famously fought with bulls at the Asan junction.

Prawash Gautam

“Kaun sala bhidega.” (Who can take me on?)

The lone figure of Sancha Pahalman stood at the junction of deserted streets in Thamel, his two hands stretched back, chest expanded and head raised, his drunken rage resounding through Thamel, Nayabazar, Paknajol, Jyatha, Thahiti, Chhetrapati and surrounding localities, and sending tremors through the hearts of local residents.

From the window of a house in Chibahal, Shankar Lal Manandhar saw that the streets were empty, and the doors of the shops and houses had been bolted, as it always happened whenever the drunk Sancha appeared on the road. A curfew-like state pervaded.

“Even during the reign of authoritarian Ranas, a common man, Sancha, forced a curfew-like state, frequently. News that Sancha was drunk spread like wildfire and people rushed inside, taking children with them. Nobody dared to come out,” said the 96-year-old Manandhar, a veteran Mathematics teacher, who was born and grew up in Kwabahal near Thamel.

Indeed, during the Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher’s reign all the way up to Mohan Shumsher, the name Sancha Pahalman–his real name was Sanuman Kayastha–-inspired both awe and fear among the residents of Kathmandu for his legendary strength.

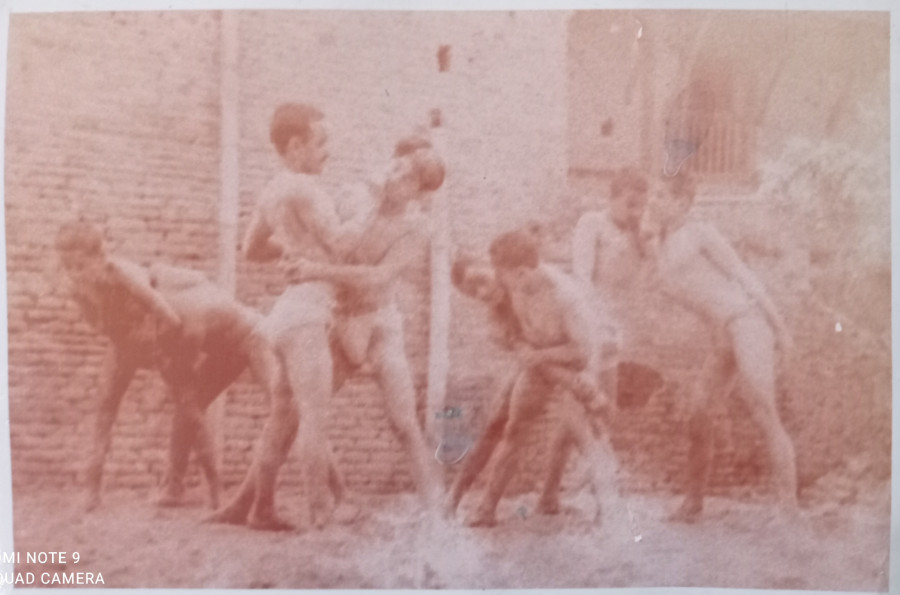

Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pande writes in his book ‘Tyas Bakhatko Nepal-Part 1’ that during the Rana regime, kushti or pahalmani–a form of traditional wrestling played on sand (pahalman refers to the practitioner of this sport, or even someone known for exceptional strength)–was a popular game in Kathmandu with wrestling akhadas–physical and social space where wrestling activities take place–situated in various locations. The Ranas employed pahalmans in their durbars for entertainment. Many Ranas themselves were trained in wrestling, like Bir Shumsher’s son Ananda Shumsher who, Pande writes, practiced with none other than Sancha Pahalman. According to historian Tri Ratna Manandhar, the Ranas also invited pahalmans from India for entertainment in their durbars. They also trained the Nepali pahalmans to fight with these Indian wrestlers.

In this backdrop, Sancha emerged as the strongest and famed pahalman of his time. But his fame as a pahalman in the wrestling games was as ubiquitous as the notoriety he gained as a domineering strongman outside of the games, something which inspired playwright Bal Krishna Sama to pen these lines in his memoir ‘Mero Kavitako Aradhana’: “When I was small, there lived a pahalman called Sancha from [Kathmandu core] city who was the strongest person of his time. Additionally, he was also a fight-monger, oppressor and trouble-maker.”

Likewise, Pande writes in his book that “Sancha Pahalman from Thahiti was famed [pahalman] in Kathmandu.”

Indeed, he gained so much fame in pahalmani that Sancha was apparently unimpressed when, towards the later phase of his life in 1962, he watched India’s Dara Singh – who was then the reigning world champion of professional wrestling (which involves staged wrestling matches) – and his brother Randhawa Singh on staged exhibitions in Sano Tundikhel. Family members and locals recall Sancha mocking them.

“Is that even wrestling?” he said with contempt.“No wrestling techniques or moves, nothing. The way they wrestle, they’ll only kill people."

Pahalman among photographers

Sancha, who was born in the early 1900s as per family estimates, belonged to a known family in Thahiti. Takha: Chhen, the Kayasthas’ palatial house bespoke Kayastha family’s wealth and power. It was from here that Sancha’s grandfather, Mani Ratna Kayastha, a businessman of jewelry and woodcarving and working for the Ranas, oversaw his extended family and business.

According to family accounts, impressed by his deft hands at carving intricate woodwork, and believing that he could possibly channelise this aptitude towards photography, the Ranas encouraged Mani Ratna’s son Chakra Bahadur Kayastha, to learn photography. Business details printed on Chakra Bahadur’s business envelope reads “Photographers to the Government of Nepal. Oil Painters, Photo Enlargers, Dealers in Photo Materials and Manufacturers of High Class Furniture.”

Chakra Bahadur’s sons and nephews also pursued professional photography, and catered to various Rana durbars. Sancha’s younger brothers Shreeman and Madan Bahadur were also photographers. How Sancha, who was the eldest son of Mani Ratna’s youngest of three sons, emerged as a pahalman amidst this family of photographers remains shrouded in mystery. Manandhar detailed a series of events that led to his rise into a pahalman.

According to this account, the boy Sancha gained a reputation as a neighborhood mischief and a beater of local boys. After his mother was unable to contain him in the house, Sancha’s father began taking him to his work in the Rana durbars. One day, a high-ranking Rana, identifying Sancha’s possibility of growing into a pahalman, promised the father that he’d send his son for training to Mumbai when he came of age.

When Sancha reached an appropriate age, the high-ranking Rana duly kept his promise by sending Sancha to Bombay, for training. There, he stayed and trained for a few years before returning to Kathmandu.

Manandhar’s account though is not verified by Sancha's family members or other sources. The 56-year-old Pradimna Man Kayastha, grandson of Sancha’s brother Shreeman, said that no credible information exists about his time in Mumbai, or if he even went there or to India at all. Indeed, no definite information exists on whether Sancha ever received any formal training in wrestling. The remotest link to Sancha’s possible training in India, Pradimna suggested, was his frequent use of the Hindi phrase “Kaun sala bhidega.”

Indian pahalmans, Asan’s bulls

Donning suruwal kamij and istakot, and short in height, Sancha was far from a strongman in his appearance, said Manandhar.

“But he was strong. Very strong, particularly his hands. If he caught somebody, that person wouldn’t get a chance of escaping his grip” said Manandhar.

As a boy, Nutan Thapaliya had seen Sancha walking the Thahiti or Chhetrapati gallis on several occasions. Growing up, he heard ample tales about his strength.

“When I was small, Bishnumati River along the banks of Shova Bhagwati Temple was a large, wide river that swelled during the monsoon,” said the 93-year-old. “A saying went that if Sancha bellowed on one side of the river, people on the other side got scared. That’s how loudly his sound reverberated.”

Sancha was well known in the Rana durbars, Ananda Shumsher practicing pahalmani with him being one indication of his connection. And anecdotes of Sancha’s strength exhibition in the durbars are popular among family members and the elderly locals.

Narayan Lal Shrestha, 76, a former Dean of Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk, was born in Thahiti, and grew up seeing Sancha and listening to his stories from his father, who was Sancha’s contemporary. Recounting his father, Shrestha said that the Ranas had once brought seven pahalmans from India for a wrestling challenge.

“Sancha was so strong that he defeated all the seven pahalmans one after the other, successively,” he said.

On other occasions, Sancha came face to face with sheep reared by the Ranas for sheep fighting.

“In those times, there was a tradition of sheep fighting,” Shrestha said. “Some Ranas reared sheep in their durbars, and ranked them based on their strength. Pointing at the sheep ranked number one, the Ranas’d ask Sancha, ‘Can you fight with that one?’ Sancha replied: “All I need to win is to hit it with a hand.” The sheep would come charging at Sancha and he’d strike it and force it to retreat. It would charge again and Sancha would strike again. After three or four times, the sheep gave up.”

But the most famous account of Sancha’s strength is what he’s most remembered for – his encounters with the bulls. Massive stray bulls with their beastly strength lay sprawling in the middle of a busy Asan junction. Often, two bulls confronted, blocking the road and terrorized the locals. A famous account has it that Sancha could separate the fighting bulls.

Shrestha described one incident that he heard.

“Once, two bulls fought ferociously, blocking the Asan junction and threatening pedestrians and locals for two whole days,” he said. “Sancha came to the rescue. He stood between the raging bulls, placed a hand each on their horns and separated them for long enough. The bulls eventually gave up and parted their ways, and calm returned to Asan’s streets.”

Sama too recounts Sancha’s encounters with the bulls in his memoir. "Once, two bulls fought on the Asan chowk,” he writes. “Sancha fought with the one that won and forced it to run away.”

“These were heavy, stray bulls, and of course, Sancha didn’t actually fight them in the sense of picking them up and hurling them away,” Pradimna said. “The truth is he could hold an irate, massive stray bull by holding its horns with his hands long enough to placate the animal and compel it to give up. This was an astonishing feat for any man to achieve.”

Bhushan Bahadur Kayastha, a fourth generation descendant of Chakra Bahadur Kayastha, said that one of Sancha’s nephews had in fact taken a photograph of an instance of Sancha's encounter with a bull, and remembered seeing the photo when he was small.

“But perhaps it got damaged or got lost,” he said.

Like the members of his extended family, Sancha did venture into photography. There actually exists a 1930 group photo of a Mathema family in Ombahal that was apparently taken by Sancha. But he didn’t make photography his serious professional endeavor.

“Sancha spent his day training with wrestlers in the akhadas in different localities or in Rana durbars,” said Pradimna.

“We had a plot of ancestral land alongside Kathesimbhu, Shree Gha: in Thahiti,” said Sancha’s 99-year-old daughter-in-law Padam Kayastha. “There, he exercised and trained others. He had even built a hand made up of iron there to practice hand wrestling.”

According to Pradimna, Ram Sharan Shrestha, father of Nepal’s foremost ornithologist Hari Sharan Nepali, was also a Sancha student, and the courtyard of his house in Chhetrapati was also one akhada.

In these akhadas, Sancha trained his students that included locals who were physically strong or were interested in wrestling. One of Sancha’s sons Luh was also a pahalman. Kale Bhai Shahi from Thahiti, who is known even today among the locals of Thahiti and vicinity as Kalcha Pahalman, was picked by Sancha and trained as a wrestler.

Apart from akhadas, Sancha also spent his afternoons in the motor repairs shop opposite Juddhodaya Public High School where Hotel Tayoma is today, said Manandhar. The four wheelers were then owned mostly by the royals Shahs and Ranas or the upper class like the Pandeys and the Thapas. Manandhar, who was around fifteen at the time, often saw Sancha from a window of a nearby house where he went to give wrestling tuitions.

“Sancha picked a Shah, a Rana, a Thapa or Pandey who’d be there to repair his motor, and overturned him on the ground on the pretext of teaching him the tricks of wrestling,” he said. “He then picked up another and repeated the same. ‘Enough, enough!’ they pestered Sancha to stop. But Sancha looked at another one and said if he too would like to learn the tricks. I felt so content to see a common man do that to the upper-class people.”

‘Kaun sala bhidega’

But Sancha’s strength wasn’t merely exhibited in harmless endeavors. Aware of his strength, Sancha swelled with arrogance, which became evident in his misdeeds.

A popular account abounds in Thahiti and Chhetrapati areas that once Sancha spread his hand before a shop, the shopkeeper had to dutifully fill that with cigarettes and betel nuts, or in sweet shops with the sweets that he desired.

Sancha’s arrogance was further fuelled by his drinking habit. His figure in the middle of the streets, roaring ‘Kaun sala bhidega', daring anyone for a face-off, became a frequent sight for the locals. And it induced them to run inside their houses, close shops, dawning a curfew-like state in Thahiti, Thamel and surrounding localities.

At times, like a goon from a Hindi film, the drunk Sancha rampaged shops, grabbing whatever he desired. The timid shopkeepers kept their watchful eyes and ears alert. News of his arrival spread like wildfire, and they bolted their doors.

Wherever brawls erupted, Sancha promptly presented himself and soon became enmeshed in the brawls himself, said Manandhar. So much larger than life was his personality that even during the great spectacles of jatras, Sancha’s presence reigned supreme. The crowds lined up the street to let the procession pass during the jatras. Sancha spread his right hand and sped, running his hand along the crowd, and whoever got struck with his hand fell from the strike, said Rajendra Narsingh Suwal, 61, a local of Chhetrapati, who has heard anecdotes of Sancha from the former vice chancellor of TU, Surya Bahadur Shakya, who was also Sancha’s student.

“Anyone he had to settle an issue with, or anyone he had to beat, Sancha did this especially during jatras,” Suwal said.

Sancha’s misadventures often landed him in prison. Alas, he reigned in the prison too. At times, he gathered prisoners and taught them wrestling, said Manandhar. At other times, he broke the iron bars, freed himself out of the cell and basked in the sun. Unable to cope with the herculean task of containing Sancha, as well as Sancha and his family’s connections to the Ranas, police didn’t lock him in for long.

Even the Rana prime minister Chandra Shumsher wasn’t incognizant of Sancha's misdeeds.

“Appreciating his courage and strength,” writes Sama, “Chandra Shumsher would order his release, telling him not to repeat his misdeeds.”

But Sancha wasn’t always a rowdy figure either, as local narratives mostly project him to be.

“The day after each drunken episode, he’d be back to his gentlemanly self,” Manandhar said. “When not drunk, he was a gentleman, like any normal family man, and went about his own way without bothering others," he said.

Fame, fall, legend

But in the memory of Thahiti and vicinity, stories of Sancha’s gentle character are overshadowed by his pahalman personality. Sancha became synonymous with strength. When in the 1950s, a pahalman named Badri Mau from Chhetrapati also started fighting bulls, locals hailed him as measuring up to Sancha's strength.

“Badri Mau also fought bulls and people started saying, ‘Badri Mau can also fight bulls like Sancha did. He’s also become as strong as Sancha Pahalman,’” said Thapaliya.

Sancha’s fame spread beyond Kathmandu Valley and, some claimed, even as far as Calcutta. Thapaliya shared an incident from the early 1970s when he was based in Banepa, years after Sancha was already dead. Two boys fought in the courtyard when one of them snapped and said something in Newari.

“I asked his mother, who was nearby, what he had said. She told me, ‘I won't be afraid even if you bring Sancha Pahalman to defend you. That's what he said.”

Alongside his increasing fame, Sancha’s drinking habit began taking its toll. A strongman suddenly found his muscular power and his glory days fading away.

“As someone who lived by dictating his terms, Sancha perhaps couldn’t cope when people started to look down upon him as he became older. So, he started drinking even more,” said Pradimna.

As a boy in the 1950s, Shrestha saw the later phase of Sancha’s life.

“He got drunk by the afternoon, and stood in Thahiti chowk, a rendezvous of roads to Asan, Thamel, Indrachowk and Chhetrapati,” he said. “He’d shout and throw mouthful of expletives at onlookers and passersby and block people from passing the junction.”

Ultimately the police intervened. They lacked the strength to fight him, but softly, they coaxed him and tied him to a metal chain and took him to the station. There they fastened one end of the chain to a boulder to prevent his escape.

“But Sancha broke free and reappeared at the chowk wearing the garland of that boulder, blurting a barrage of obscenities,” Shrestha said. “He went after people again, forcing them to return towards the same direction they’d come from. People also teased him and then he blurted out obscenities again and chased them.”

Next day, the entire episode got repeated.

Eventually, age and alcohol sapped vigor off Sancha’s hands. According to locals, now Sancha no longer commanded the same domineering power in the community he once lorded over.

Seeing this frail Sancha, Sama wrote in his memoir, “Even today, Sancha can be seen around, so frail and sapped of energy, devoid of shine, that he'd shy away, even if a 15-year-old passed by him.”

In his twilight years, Sancha turned more religious, spending time singing and listening to bhajans and visiting the Shova Bhagwati Temple and other surrounding shrines every morning, said Padam.

According to her, Sancha was in his early sixties when he died around 1966/67. By this time, he was already a legend. Almost a mythological character on whose tales of notorious strength a third generation was already coming of age.

And so, whenever the locals of Thahiti, Chhetrapati and its vicinity are asked today, “You know, there was once a Sancha Pahalman?”, they reply almost instantly to the effect, “Oh yes, Sancha Pahalman. I didn’t see him, but my father told me ....”.

Thus continue the tales of Sancha's legendary strength whose ripples continue to resonate through the gallis of Kathmandu’s core.

Gautam is an independent researcher with an interest in social history.

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu