Culture & Lifestyle

When snow came and stayed in the Valley

Remembering the joys and hardships brought on by the 1945 snowfall.

Prawash Gautam

The expansive ground, the path, thin foliage of trees, and every possible open surface all swathed in a white blanket of snow. Tiny figures, possibly children ready to play in the snow as an adult looks on.

The picturesque, dreamy scene suffused in chilly white and gray, at first glance, is straight from some European winter landscape. Until a closer look brings to the fore the stupa so native to Kathmandu and the typical Rana-era building. A closer look still reveals the daura suruwal, istakot and dhaka topi the adult is wearing.

Indeed, this photo – showing the view from the corner of Bir Hospital towards Kantipath (the stupa was later relocated to Bhagwan Paau, Swayambhu) – is taken by photographer brothers Santa Bahadur Karmacharya and Samar Bahadur Karmacharya of Masang Galli, Kel Tol, and captures Kathmandu's rare moment of being covered by snow.

Following several cold, rainy days, heavy snowfall occurred in Kathmandu for some three hours on January 6, 1945. By the time it stopped, the valley was buried under a thick layer of snow several inches deep.

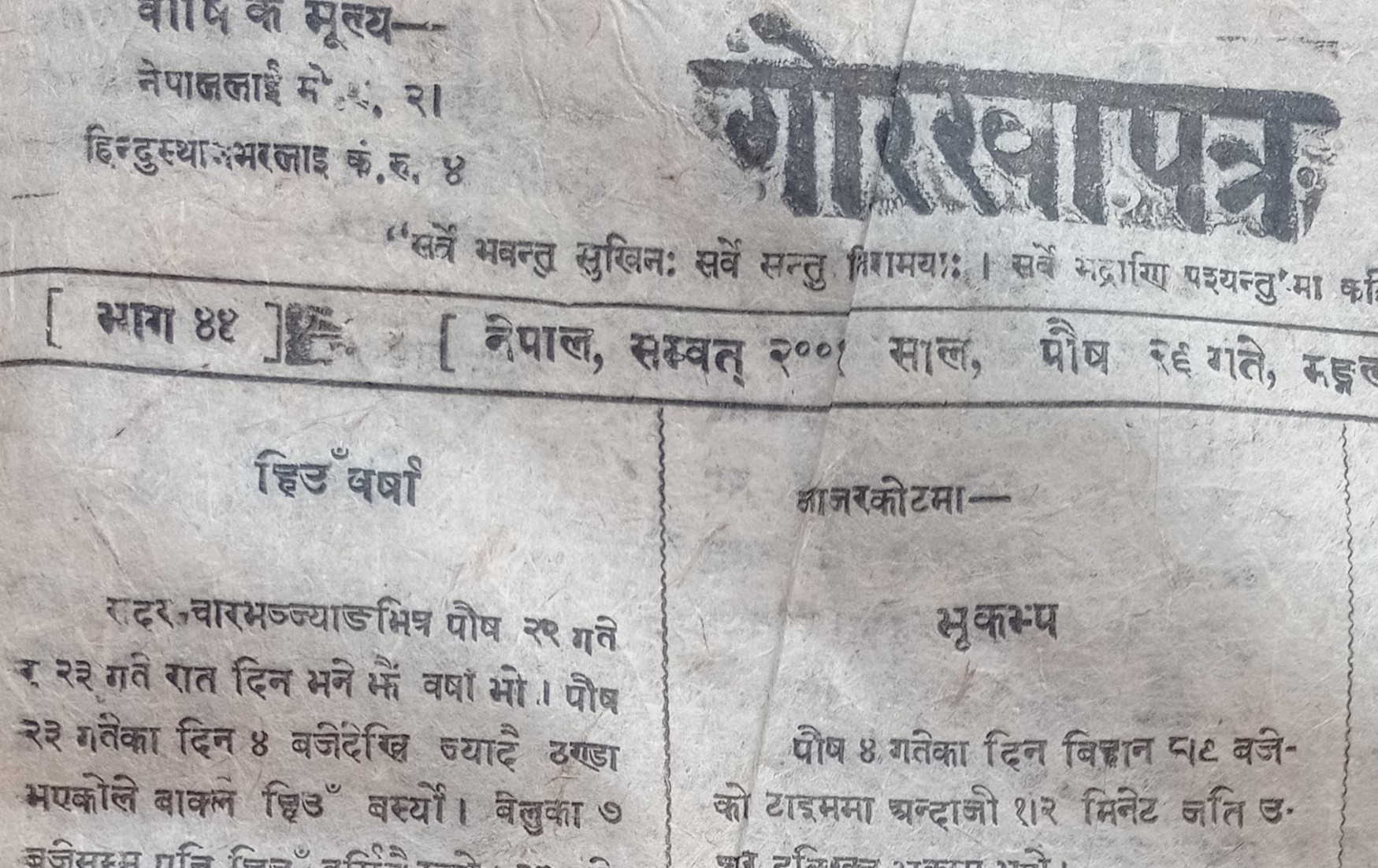

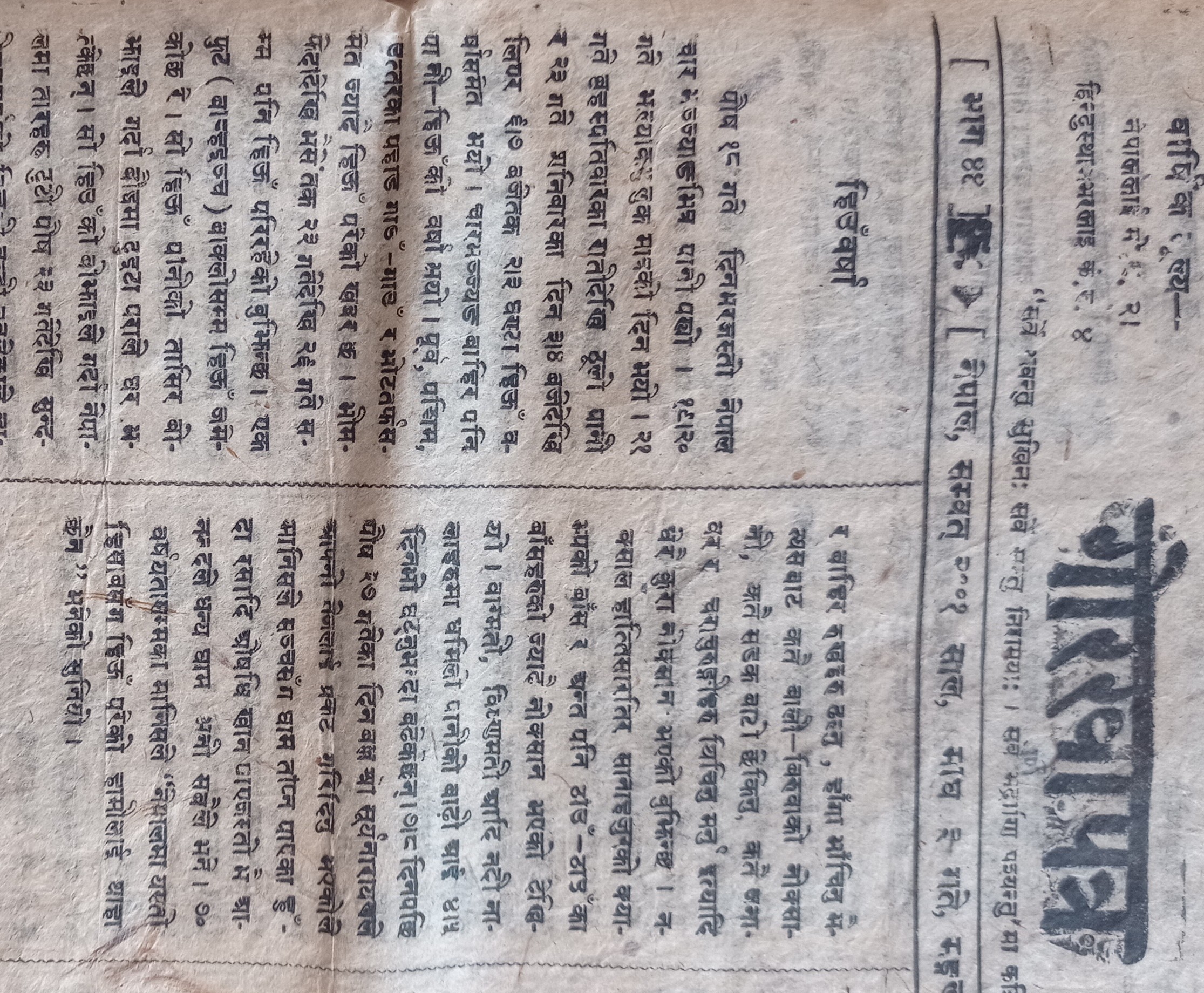

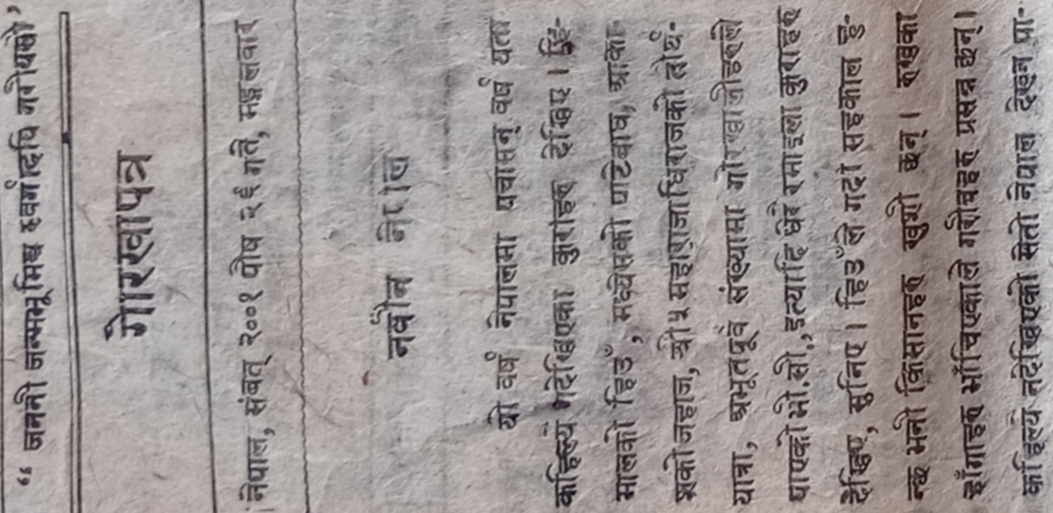

Gorkhapatra, the state-owned and Nepal’s only newspaper then, wrote in its editorial titled “Navin Nepal” [New Nepal] on January 9, 1945 that this “snow from mountains” was among the "many never-before-seen amusing things witnessed in Nepal this year." Its detailed coverage of the snowfall on January 16 titled "Snowfall" stated that “Those above 70 years of age have said, ‘We've no knowledge about such snowfall occuring in Nepal [Kathmandu]’.”

The snow stayed for several days and was a source of celebration for Kathmandu residents. But it also stalled movement and daily life, destroyed crops, killed birds and animals, and even resulted in the death of a person. The snowfall also became an impetus for an important social change.

Piercing cold, then snow

Thick fog engulfed the air, deep frost-covered swathes of ground, and thin ice sheets formed on pond surfaces – Kathmandu's once-freezing winters are fresh in the memories of its elderly. Minpachas (min means fish, pachas is fifty in Nepali) – fifty days, in particular, were so cold that even fishes deep under the waters hid below the rocks for fifty days to keep warm. During many winters, Kathmandu's people had seen surrounding hills like Shivapuri and Phulchoki enveloped in snow, but never the valley core. In the winter of 1945, this was to change.

Rain battering over chilly, dark days was what preceded the snowfall, detailed Gorkhapatra in "Snowfall".

"It rained for almost throughout the day and night inside Charbhanjyang Nepal [Kathmandu Valley] on January 1. It was mostly gloomy on January 2 and 3. It rained heavily from the night of January 4, Thursday," it said.

Eventually, the piercing cold dipped further, resulting in snowfall.

"On January 6, Saturday, it snowed for 2/3 hours from 3/4 pm to 6/7 pm," read the report.

According to Gorkhapatra and oral testimonies, Kathmandu was covered in a thick blanket of snow as deep as 5 to 6 inches that took several days to melt, spreading a spirit of cheer and wonder among its habitants.

Spirit of joy as ‘pluffs of cotton dropped from the sky’

Gorkhapatra captured the spirit of excitement pervading in Kathmandu air due to the snowfall. "The farmers are happy with the belief that snow brings greater harvest," stated the editorial “Navin Nepal”. "The poor are delighted because tree branches have broken off. Children too are happy at seeing the [snow-covered] white Nepal [Kathmandu] that was never ever seen before."

Right from the moment they floated down Kathmandu skies, snowflakes showered treasured moments on Kathmandu folks.

Shankar Lal Manandhar, a veteran mathematics teacher, who was 17 when he saw the snowfall, recalled the moment the falling snowflakes enchanted his neighbourhood of Kwabahal near Thamel.

“The weather had been bad and it was raining, and suddenly, like coarse, disintegrated grains of cotton rising in the air when quilt makers beat cotton with sticks, snowflakes started dropping from the sky," said the 96-year-old. "'It's snowing!' people exclaimed and looked out the windows. Everyone had fun.”

7-year-old Govinda Khanal and his friends were also enthralled when snowflakes fell around his home by the Bagmati river in Shankhamul.

“Like clear cotton, soft snowflakes started dropping from the sky,” 86-year-old Khanal recalled. "We scooped the snow into our hands, ran and danced around. It was fun.”

“The snow fell like fluffs of cotton," 67-year-old author Kamal Ratna Tuladhar recalled his late mother telling him about what she witnessed as a young girl on that day. “People walked around carrying umbrellas to shield themselves from the snow. When the umbrella got too heavy, they would shake the snow off.”

Once the snowflakes settled on the grounds and surfaces like a carpet, its whiteness lighted up Kathmandu’s entire surroundings.

“Once the snow covered the ground, the entire surrounding turned bright due to the snow’s light [whiteness],” Khanal said.

Manandhar remembered that “when the sun shone over the snow, the sky dazzled as if a light had shone over many mirrors.”

For the next several days, Kathmandu’s children had discovered their favourite play.

“Children found it very fun, and ran around and jumped on the snow,” Manandhar said of children in his locality. “They made snowballs and threw at each other. Seniors would call from inside, ‘Oh, you might catch a fever. Come inside and sit around the fire’, but they didn’t pay heed.”.

Goraksha Bahadur Nhuchhe Pradhan, 95, the retired secretary of the Nepal government, who was 16 then, recalled playing with snow with other children in the family. “We went to the open rooftop of our five-storied house to play with the snow,” he said. “We made balls from snow and threw them at each other.”

As children rejoiced at the moment, farmers had a more lasting reason to be happy owing to snowfall's moisturizing quality for crops.

Manandhar recalled that the productivity of Kathmandu’s farms increased after the snow. "Snow apparently is manure for farmlands," he said. "[Kathmandu’s] farmlands became highly productive due to the snow. [Farmers] didn’t even have to irrigate the land. As snow above the fields started to melt, it provided water to the farmlands."

Alongside its delights, snow also brought misfortunes.

Snow troubles and tragedy

Weather and crops brief on Gorkhapatra on January 19 stated, “As it snowed and turned cold and shops were closed in the entire Bhaktapur area on January 6, [people] faced difficulty as they couldn't shop for daily food supplies.”

Thick snow blocked roads, halting movements and causing difficulty in getting supplies in the entire valley for several days.

“It happened to be a time when schools were closed due to minpachas holidays,” Manandhar said. “Offices too were like being closed because they didn’t make attendance strict given the difficulty of commuting. Since shops were closed, it was hard to get supplies. It was like chaos.”

Freezing cold was worsened by the darkness descending due to the damage to the electricity lines. As Gorkhapatra wrote in “Snowfall”, "The weight of snow broke wires, so there was no electricity in the Sundarijal area starting January 6. [...] Electricity finally resumed in the main roads and bazaars only on January 10/11. It also resumed in the transmission lines to durbars. But [commoners’] houses are yet to have uninterrupted electricity. The troubles brought on the people due to cold and darkness is indescribable.”

Keeping warm became a challenge. “There were no heaters in those days, and we relied on makal [earthen pot with charcoal for heating],” Pradhan said. “My mother was an asthma patient, and we had to take extra care to protect her from the cold.”

Gorkhapatra wrote in “Snowfall” that the sun did not appear for a week. It became so cold that when the sun ultimately “spread its rays … people felt that finally getting the chance to bask in the sun was like having been provided medicine. Content, everybody thanked the Sun.”

Those living in kachhi houses – made of materials like stone, unbaked bricks, wood and mud – had more to take care of than cold. Manandhar recalled that such houses faced damage due to the snow.

“As snow gathered over kachhi houses, its weight pushed and broke certain portions of the houses, causing difficulty to their inhabitants,” he said. “Meanwhile, roofs with corrugated sheets were not sloped, they held more volume of snow. So their inhabitants lit big fires from inside so the heat melted the snow.”

In Bauddha, two houses crumbled. "Two thatched-roof houses crumbled in Bauddha due to the force of the rain and snow, but there were no loss of lives," said the report "Snowfall".

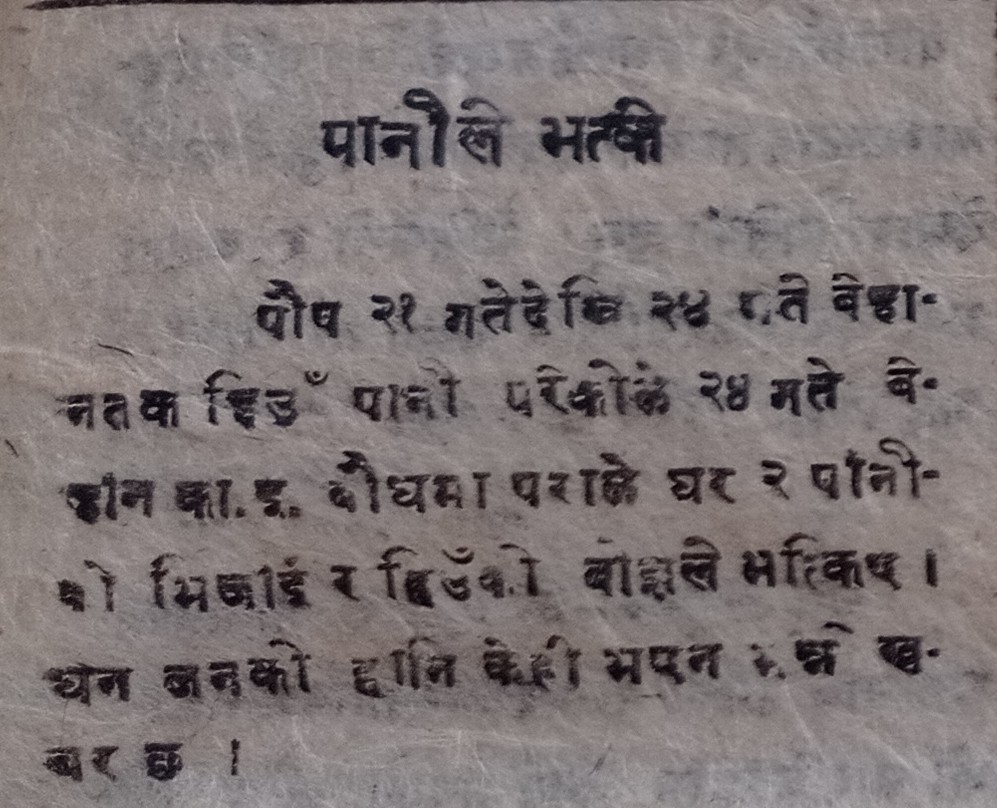

Snow and rain also flooded Kathmandu rivers and rivulets. “Bagmati, Bishnumati and other rivulets in Kathmandu have been flooded with muddy waters and, since the past four-five days, instead of reducing, they have become bigger,” wrote the report.

The report further detailed the loss of plants and animals. “Falling trees and breaking branches have destroyed crops and plants, blocked roads, pressed and killed animals and birds in various places inside and outside Charbhanjyang. Bamboo groves in [...] Hattisar and other places saw huge destruction.”

Most tragically, a farmer named Kedar Tamang died after being caught in the snow on January 6 while returning home after selling wild yams in Kathmandu. A news article titled “One dead” on January 16 wrote: “It started to snow while he was midway. Tamang could neither continue homeward nor return towards Kathmandu. Having [taken cover under a tree], he died there. Apparently, his relatives came on January 9 and pulled out his body by removing snow that had buried his body up to the hips, took it home and performed funeral rituals as per their culture."

An enduring legacy

By the time the snow melted and life returned to normal, the snow had made an enduring socio-cultural impact.

In the strict caste-based society of the 1940s, cooking and eating were viewed as sacred acts. And so, women from Brahmin families were barred from wearing blouses in the kitchen, and could only cover their bodies with saris while cooking.

“Blouses or other clothes were believed to be impure because they were stitched,” explained Khanal, who was raised in a conservative Brahmin family. “Saris, meanwhile, were considered pure as they were not stitched.”

In an interview with veteran journalist Bhairab Risal in 1999 for a Radio Sagarmatha program Uhile Bajeko Palama when she was 86 years old, a Kathmandu local Ratnakumari Nepal describes difficulties women faced while cooking during winter. "It would be very cold in the houses of that time," she says. "Moreover, there was no tradition of wearing blouses when cooking.”

“There was once a big snowfall," she adds, referring to the snow in 1945 when she was 30 years old. "After that, [women] were allowed to wear blouses [to the kitchen due to the cold]. Otherwise, we wouldn't get to wear blouses."

Although, according to Khanal, in Kathmandu this practice was in existence even until the 1960s, the snowfall became an impetus to end this tradition.

When Kathmandu witnessed its next snow 63 years later in 2007, it was nothing close to the 1945 snowfall in the extent of joys and troubles the latter brought. Snowflakes dropped for a brief moment and melted the instant they touched the ground. And so, 1945 was a singular year of amusing snow in Kathmandu’s memory that has not been repeated in the long life of an individual like Manandhar.

“All these years I’ve wondered if Kathmandu will get such snowfall again,” Manandhar said. “I'm still waiting.”

21.02°C Kathmandu

21.02°C Kathmandu