Culture & Lifestyle

A Kathmandu home for Amritsar Sardarni

Soon Kaur’s world and hope became intertwined with her husband’s love of Kathmandu, their two children, and their family’s struggle for identity as Sikhs..jpg&w=900&height=601)

Prawash Gautam

“Won’t we reach the plains again?” asked 17-year-old Jagdish Kaur between tears and a muffled voice.

As the Kathmandu-bound truck crossed Bhimphedi and began ascending the high hills through the narrow, hairpin bends of the Tribhuvan Highway, she was suddenly struck by the grim reality that her new home would be the hills where, she had heard, life was hard.

“No,” replied the Sardar driver and family acquaintance. “You’ll now have to live in the hills.”

In 1963, Kaur travelled to Kathmandu as the bride of a second-generation Nepali Sikh, Hardayal Singh, an engineer of the Nepal government. His father, Manohar Singh, also a reputed government engineer, had migrated to Kathmandu from Rawalpindi in the then British Raj in 1931. Hardayal was born in Kathmandu’s Bhonsiko Tole in 1936.

“You cried throughout the journey,” the driver would recall years later.

From Punjab’s buzzing city of Amritsar spread on the plains and alive with the sounds of bicycles, rickshaws and taxis to the sleepy valley of Kathmandu. A place whose food and lifestyle were no match for the Punjabi way she had grown up with. On top of this, finding herself in the dilapidated government quarters of her new family, with no friends and under the controlling in-laws who feared that the city girl would never return if she went to visit family in Amritsar, she missed her siblings and parents and longed for Amritsar.

“At first, I didn’t like it here. I hated this place,” she said. “I regretted my decision to come here.”

Soon Kaur’s world and hope became intertwined with her husband’s love of Kathmandu, their two children, and their family’s struggle for identity as Sikhs. Her heart was torn between Kathmandu and the desire to settle down in India, leading to her lifelong quest for a place to call home.

Amritsar to Kathmandu

Kaur travelled with her groom and his family on a train from Amritsar to Raxaul and from there to Birgunj by bus. In Birgunj, they boarded the Kathmandu-bound truck.

The truck dropped them off at Tripureshwar. And a coolie began unloading the luggage and tying them on his back.

“Why? We go on foot? No rickshaws?” she asked, expecting Amritsar-like streets.

“Here, we don’t have rickshaws,” she was told to her dismay as her groom and father-in-law led on foot, and she followed.

Her new house was one of the government quarters made of mud and unbaked bricks lining the main street of Bagbazaar. A dilapidated two-storied building on the verge of crumbling. Bricks coming off the compound walls. No running water. Behind the house stretched foul-smelling swamp-like land, and snakes roamed the building’s compound and backyard.

“Saddened that I now have to live in this hilly area, I was consoling myself with hopes that my new house was nice. But it was right on the main street and so dirty. I felt dejected,” she recalled.

Her sorrow at the state of the house was augmented by cultural differences. Where tea flowed like water in India, it was a rare drink here, and after a cup of tea around five in the morning, she waited for her father-in-law’s return from work for the second. In Amritsar, she ate little pulau or roti and curd in the morning; in Kathmandu, to her amazement, heaps of daal, bhat and tarkari were served to Hardayal and Manohar at 8 in the morning. Even the flour for roti was gritty.

“This flour contains grits, mother. It’s not edible.”

“If everyone else can eat it, can’t you?”

And in the sea of Kathmandu women draped in saris, she distinctly stood out in her kurta shalwar.

Love blossoms in Kathmandu

Kaur had just completed her diploma when distant relatives brought a marriage proposal.

“In those days, it was a matter of prestige if the prospective groom’s family asked for a girl in marriage,” she said.

Some family members protested sending her that far. But Hardayal was a Lucknow University-graduated engineer employed with the Nepal government. Manohar was a well-reputed government engineer in Kathmandu who King Mahendra had decorated for his distinguished contributions to the country. Her parents didn’t want to miss such a respectable family.

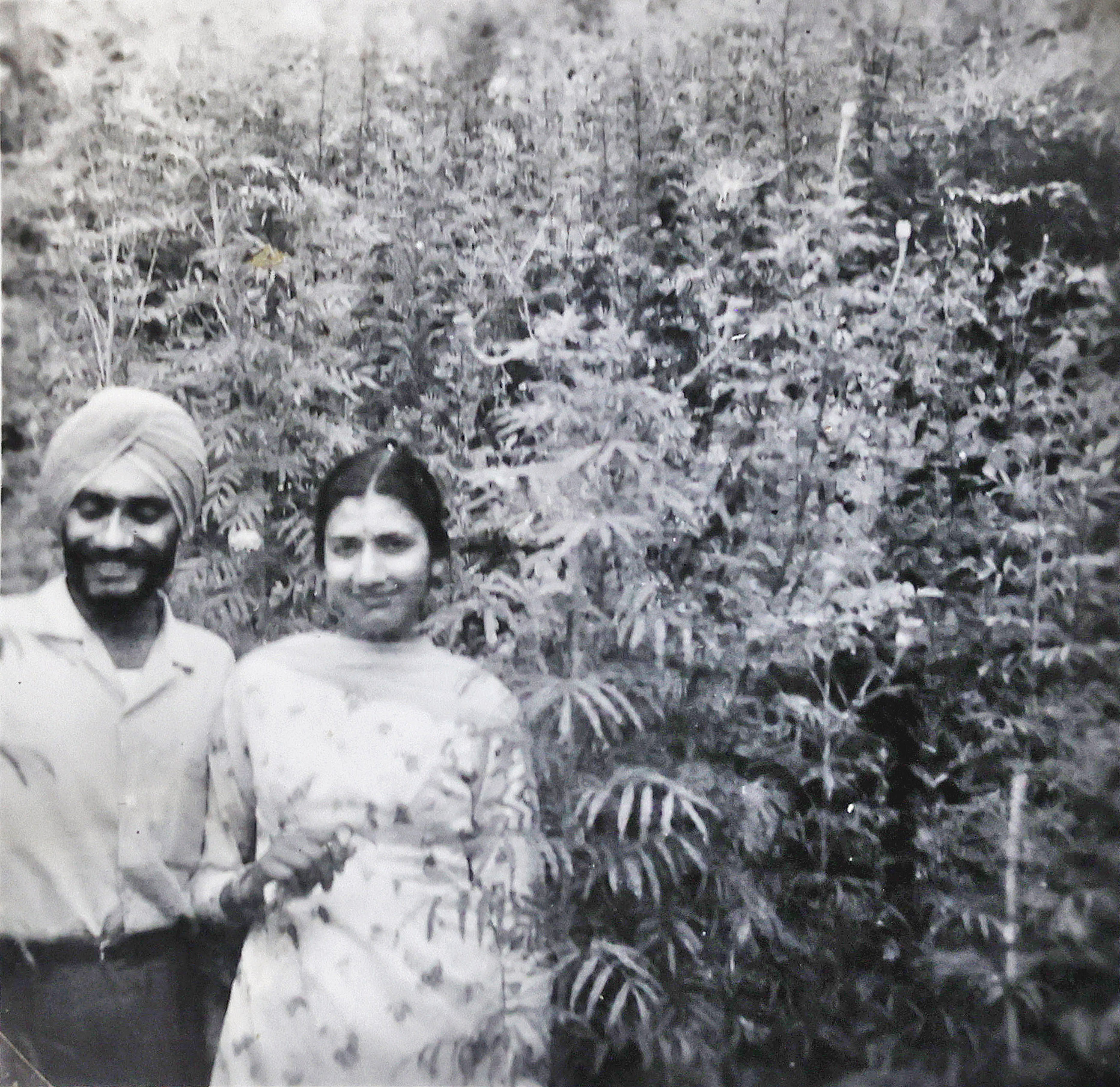

Amritsar’s plains to Kathmandu’s hills, nerve-racking journey through the Tribhuvan Highway, old rickety house—Hardayal clearly saw the reasons behind his wife’s unrelenting tears. He showered extra love. On weekends, he took her to Sundarijal and Jawalakhel. Or to historical gurudwaras in Balaju, Shova Bhagwati, Pashupatinath and other locations.

“Kathmandu was all green and beautiful. Not like today. I liked going out,” she said.

She started seeing that Kathmandu was to Hardayal what Amritsar was to her. Their son Jeetendra was born in 1968, and daughter Rupender two years later. A world of her own was evolving in Kathmandu. Later when Hardayal would encourage her to visit India, she would refrain from going.

“I worried for my house, my children,” she said. “I couldn’t leave my children.”

Between Kathmandu and Amritsar

Little did Kaur know that hills would be key to her destiny. From Amritsar, she saw a panoramic view of the distant hills. But she never wished to travel to those hills. She never climbed Kathmandu’s hills either, only admired them from afar. Like her feelings for those hills, despite her own world evolving around her young family, she never completely felt at home in Kathmandu.

For one, the deplorable government quarters disheartened her.

“Babuji,” warned a neighbour to Manohar. "Your house could collapse anytime. The walls and roof are fragile.”

And already finding it hard to adjust to Kathmandu’s staple of daal bhat, she felt oppressed by the long, idle afternoons.

“My mother-in-law went out to friends, and I stayed home like a prisoner,” she said.

There were Punjabis at Putalisadak. But the mother-in-law didn’t let her visit there. Alone, her thoughts flew to her parents and siblings in Amritsar. But for the first four years in Kathmandu, she wasn’t allowed to visit Amritsar.

“My mother-in-law knew that I was a city girl and that I didn’t like the hilly way of life,” said Kaur. “She feared that if I went to Amritsar, I’d change my mind and never return.”

Later, when she faced no restrictions to visit Amritsar, hills confined her in Kathmandu.

“I feared travelling via the scary Tribhuvan Highway, so I visited Amritsar as little as possible,” she said.

Sometimes the mother-in-law took her to afternoon visits.

“Who's this beautiful girl?” a woman relative asked during one visit. “How did you manage to bring such a beautiful girl to this distant Kathmandu?”

“My mother-in-law didn’t say a word. She was very clever,” Kaur said. “She’d convinced my relatives to marry me off to far-off Kathmandu. My family had been somehow tricked.”

Kaur didn’t mention her sorrow when she wrote to her family. In every letter, first, her mother-in-law detailed how they had kept their daughter well. Then her father-in-law further embellished the mother-in-law’s assertion.

“In the tiny remaining space in the end, I wrote that I was well, I was happy,” she said. “What else could I write when my in-laws read what I had written before posting it.”

Her parents and sisters learnt that not all was well when they visited Kathmandu after the mother-in-law passed away in 1973. “Oh, what a house I married off my daughter to,” lamented her father and cried bitterly on seeing the house.

“You’ve got to shift somewhere else beti,” told her parents. “This house could collapse any moment.”

Two days after her parents left, the house collapsed. She was inside her room with her children and a sister who had stayed back. Luckily they forced open the door and rushed out.

“God saved us,” she said. “Otherwise, with the two-storied house collapsing, it would be our end.”

Alongside the reasons augmenting her wish to settle in Amritsar was the reality of her family’s roots in Kathmandu.

Kathmandu was inseparable for Hardayal. He had a deep love for Bhonsiko Tole and went there to play cards with friends on Saturdays until late in his life. He spoke fluent Newari and had all his friends here. For his contributions as a Department of Roads engineer, he was decorated with distinguished medals by King Mahendra and King Birendra. For Kaur’s children, too, Kathmandu was all that they had known.

Paradoxically, her family’s sentiments contrasted with their struggle for identity. Because Hardayal was a turban-wearing Sikh, people often asked if he was Indian, and having to prove his Nepali identity hurt him immensely. Kaur heard from her mother-in-law how Hardayal came teary-eyed from school, his turban removed by friends. Now, Kaur saw Jeetendra return home in the same state.

“I told him I didn’t want to stay here,” she said. “Why was he living where he wasn’t treated well? My mother-in-law and I pestered him to settle in India. ‘I’ll never go away, I’ll make a house here,’ he said.”

A Kathmandu home

.jpg)

In 1972, Hardayal built a spacious one-storied house in Jawalakhel. Kaur made a garden around its compound.

“Once he brought me to Jawalakhel and showed me this land,” she said. “‘We’ll build our house here,’ he said. I liked this place. It was a time when Jawalakhel was far from crowded settlements.”

In this house, she saw her children grow and Hardayal rise in career. As Manohar retired and entered old age, Kaur engaged in long conversations with him about his destiny that brought him to Kathmandu, his struggles and his burning desire to settle down in India one day, a story that resonated with her own.

In 1992, Manohar died.

Decades had passed since her arrival in 1963. Because she dreaded travelling by hilly roads, she didn’t visit India as much as she wanted to, and her parents and siblings rarely visited Kathmandu.

In 2009, her husband suddenly passed away at the age of 71 while he still had the enthusiasm to live and pursue his numerous passions. Sometime before his death, she found him ominously taking out photographs from albums and burning them.

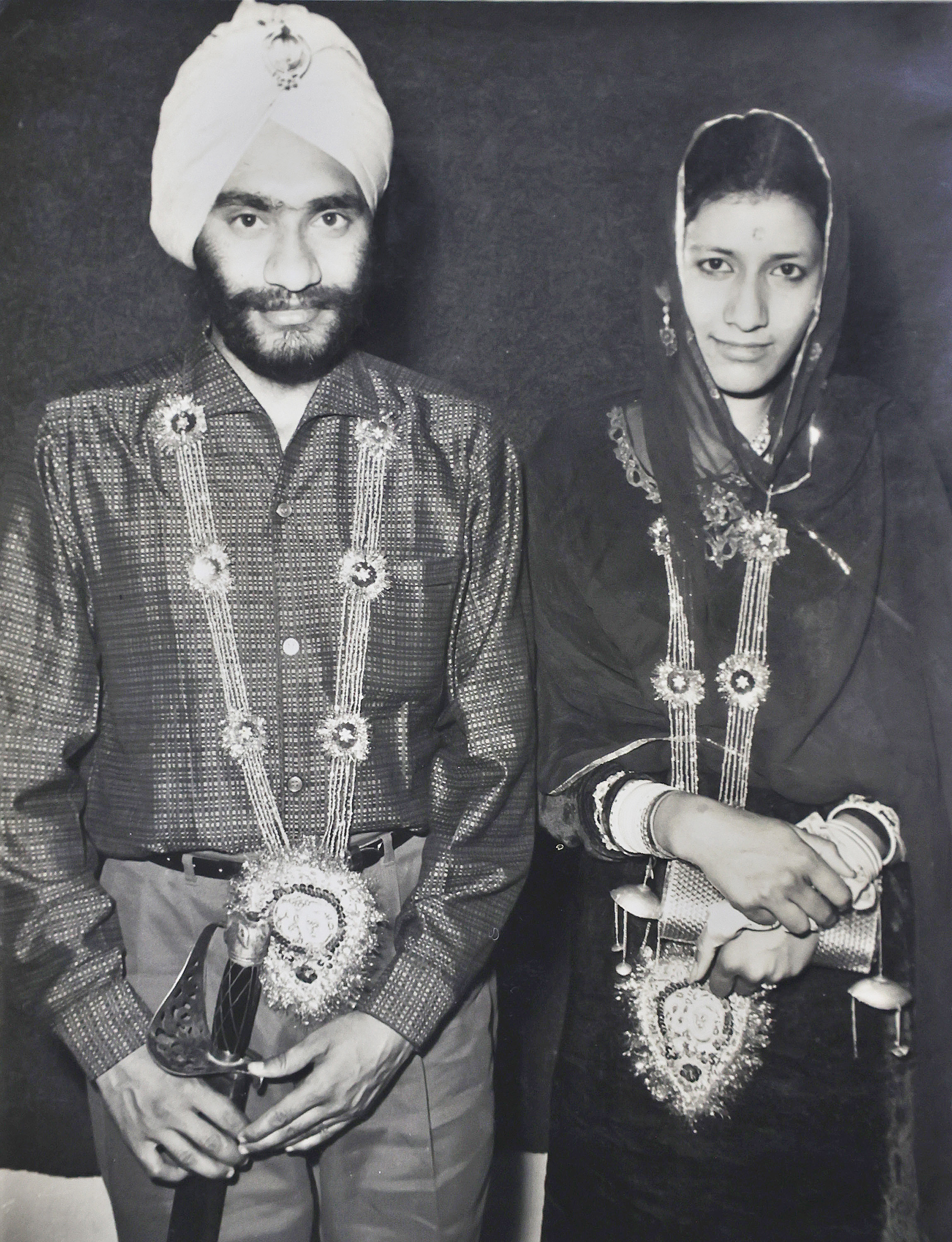

“Why are you burning all these?”

“We all have to pass one day. What’s the point of keeping these?”

“Even the marriage photographs? You won't burn those, will you?”

“Yes. All.”

She rescued the marriage photographs.

“Suddenly, he fell ill one day. Our daughter called an ambulance,” she said. “Right before our eyes, he passed away before we even reached the hospital.”

Like his father, Hardayal was cremated on the bank of the Bagmati river in Thapathali.

Wound of Hardayal passing away still fresh in her, she saw her son struck by illness. “He almost died,” she said of his recovery.

Kathmandu was now a web of memories hard to leave behind. And India, a broken link.

“Sometimes I cry at how my link with my brothers and sisters in India have broken,” she said. "It's love that connects. After my parents' death, we siblings have become so distant."

Meanwhile, in the living room of her house, its walls decorated with the portraits of King Mahendra conferring Gorkha Dakshin Bahu on Hardayal, Manohar peering down with the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu and other decorations on his chest, and 17-year-old Kaur when she first arrived in Kathmandu in 1963, she tells me of her family’s continuing struggle of identity.

“How well do you speak Nepali being an Indian?” a shopkeeper asked her a few years ago.

Over the decades she has learnt to largely accept such questions. For her home in Jawalakhel is where Kaur finds the love that connects. Here she lives with her son and granddaughter. Her daughter lives nearby and frequently visits with her son. Sometimes, her Indian relatives call her.

“Auntie,” said her sister’s daughter in Dehradun in a recent phone call. “Come visit Dehradun. It’s just like your Nepal.”

Half teasingly, she said, “What new do I come there to see if it's no different from my Nepal?”

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu