Culture & Lifestyle

A silent keeper of nine Newa caste traditions

Udaaya Museum holds the legacy of the Udaaya Samaj, with rare photos, traditional tools, and manuscripts dating back to the Rana era.

Anish Ghimire

Ason is a sensory overload. As you walk into the area, the scent of spices mingles with the aroma of food while buyers rush through the alleys, visiting shops that sell everything from textiles to bullion.

For many like this scribe, who grew up in urbanising areas outside the valley’s historical core, Ason has always been a chaotic, commercial hub—a place to bargain and shop. But beyond its commerciality, the area carries historical and cultural significance.

In the middle of Ason Tole, among the crowd’s din, lies a century-old house quietly standing on its past glory called Udaaya Chen. This building houses the Udaaya Museum, established in 2014.

It was cousins Aabhushan Tuladhar and Pranidhi Tuladhar—founders of the Instagram page ‘The Last of Kathmandu Valley’—who led me here. As residents of Ason, they have spent years documenting the city’s old architecture, hoping to capture what remains before it disappears.

If you are in Kathmandu Durbar Square, stroll half a kilometre to the northeast to reach the museum. But if you are coming from Thamel, you should head south for about 500 metres. The ground floor of the building houses the ‘Indrayani Music Shop & Institute’. Looking up, you can see a signboard that reads, ‘Udaaya Museum’.

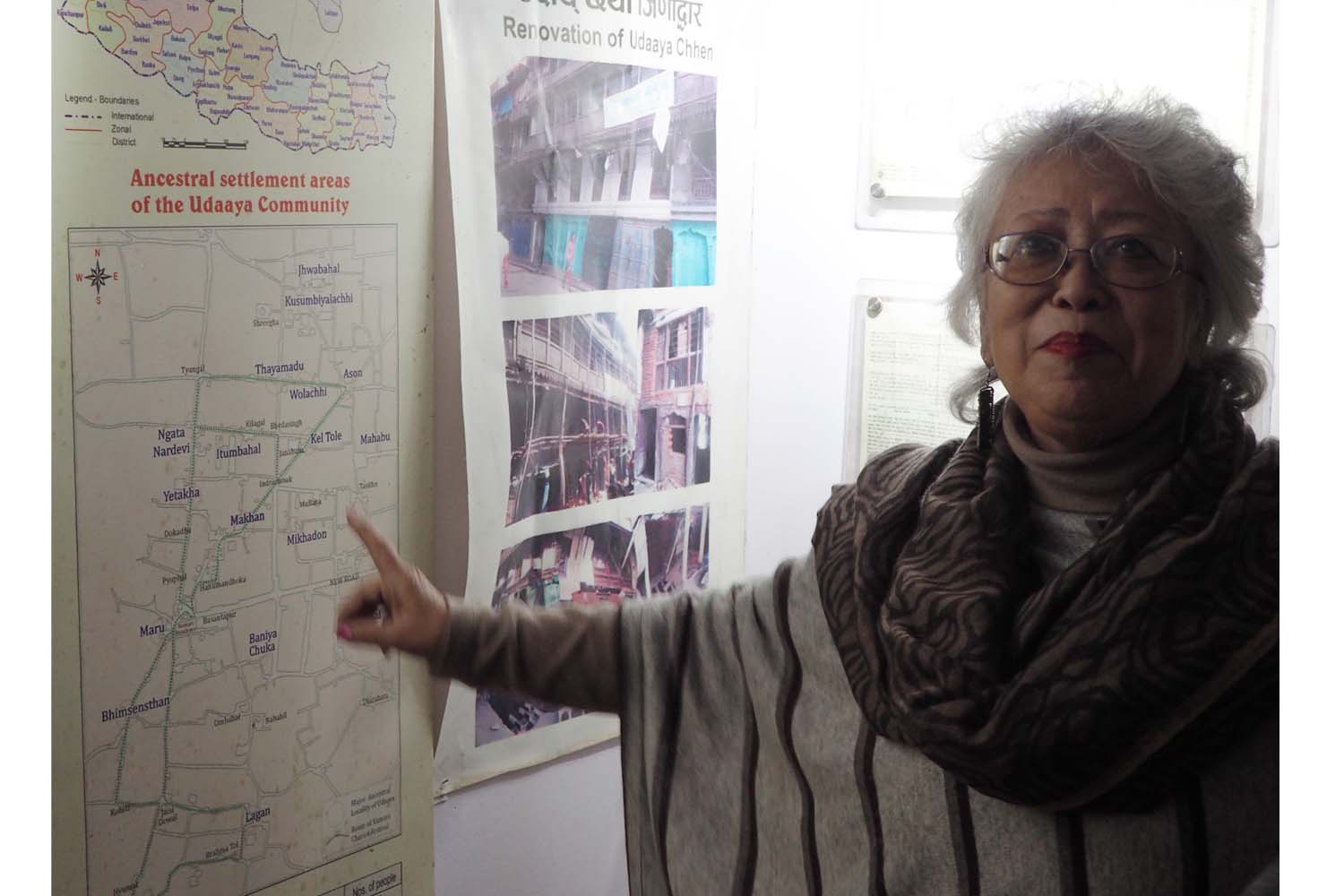

This museum is a gateway to the Newa culture, particularly of the Udaaya Samaj—a socio-cultural community made up of nine Newa castes—Tuladhar, Sthapit, Tamrakar, Kansakar, Sikhrakar, Bania, Sindurakar, Shilakar and Selalik. Formed in Nepal Sambat 1117, the Udaaya Samaj was established to preserve and promote the community’s distinctive cultural activities and welfare.

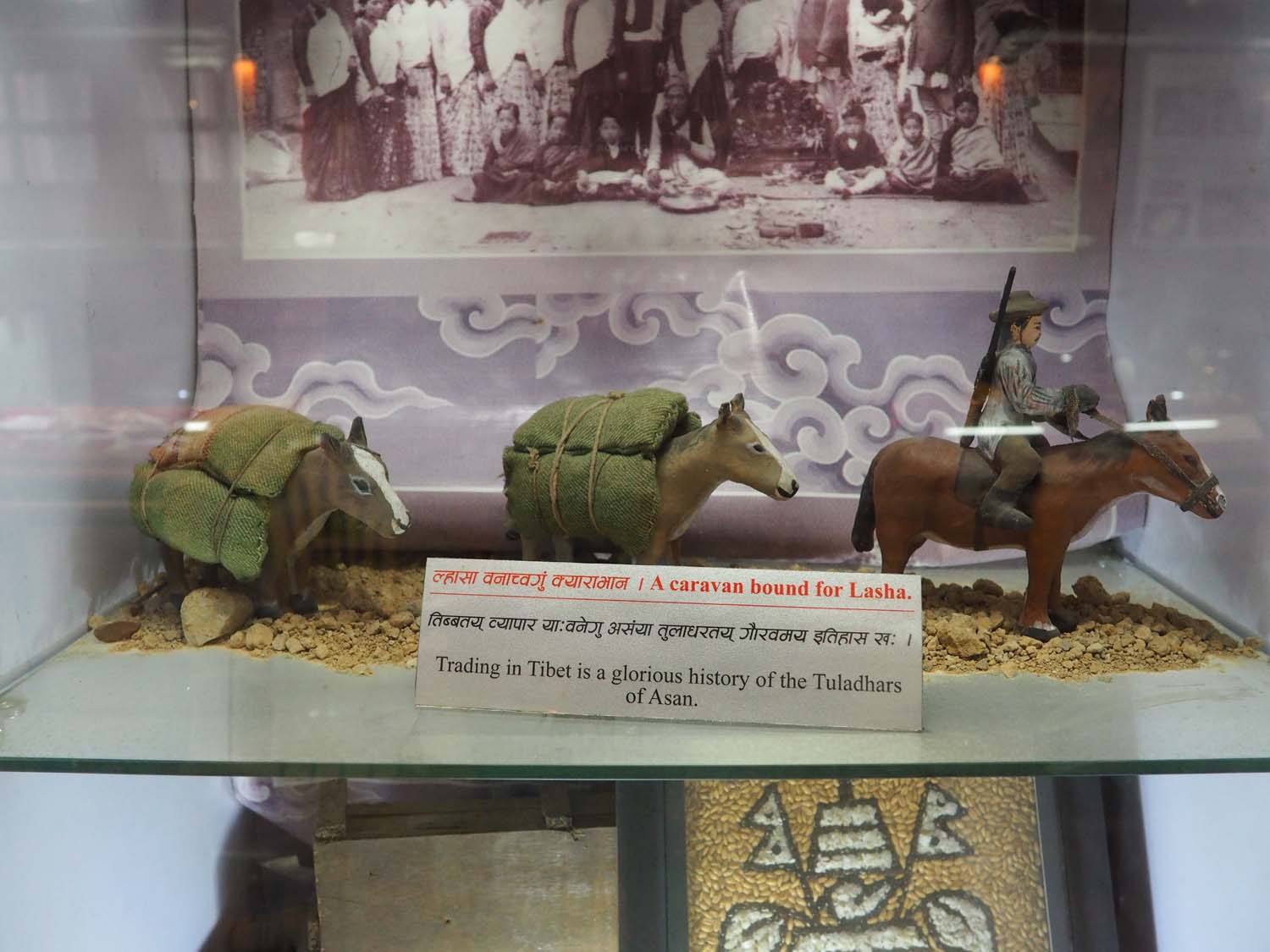

Each of the nine castes that form this community has their distinct profession—Tuladhar (scale-holders), Sthapit (carpenters), Tamrakar (copper metal worker), Kansakar (bronze metal worker), Shikrakar (tile roof builders and roof repairera), Bania (local trader and ayurvedic pharmacists), Sindurakar (weaver of special clothes for deities), Shilakar (stone masons), and Silalik (caterers of sweetmeats).

However, with the introduction of modern education, manual professions are looked down upon as people chase white-collar jobs for social status. Since original skills and art are fading and the Udaaya community is on the verge of being listed as ‘endangered’, the museum was established to preserve what remains.

After entering the building and climbing the steps, I was greeted by cheerful Sumon Kamal Tuladhar, the museum curator and one of its founding members. “Udaaya Samaj is a small community within Newa community,” she tells me.

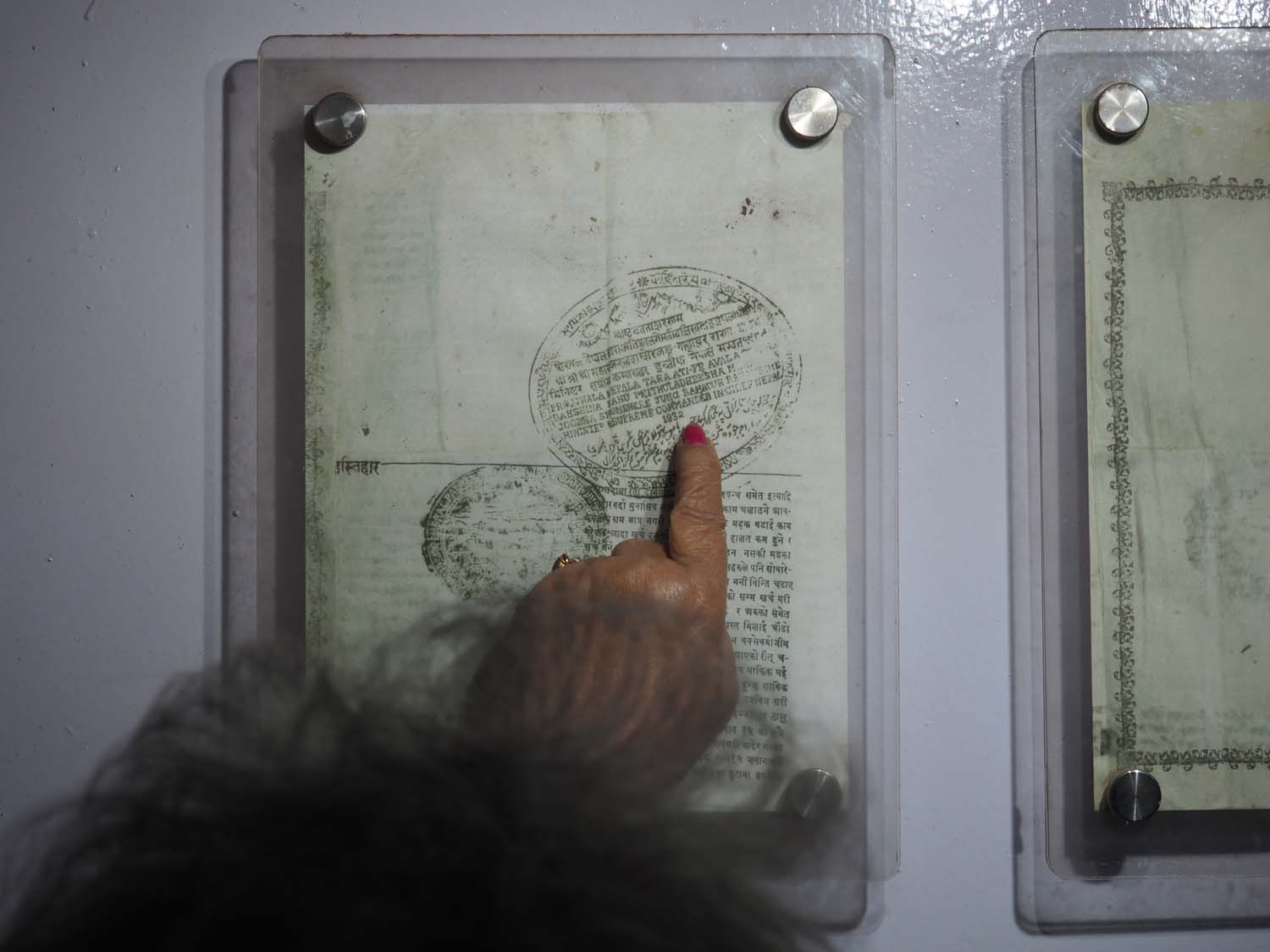

Inside the museum is a document dating back to 1932, signed by Rana Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher, enlisting the behaviours (byabahar) of the Udaaya community. Named ‘Udaas Jaatko Byabaharko Kitab’, this book acts as an instruction manual for the people of the Udaaya Samaj.

For example, when taking the news of childbirth from the husband’s home to the girl’s home, the amount of food that needs to be sent to the girl’s place is documented in the book. “The Ranas set this rule for us due to various inconsistencies in our cultural behaviours,” says Sumon. “The act of sending food and clothing turned into a competition, with people competing to send more food to their daughter’s home. To put an end to this, the Ranas provided us with a rule book.”

The original document is printed on traditional Lokta paper, while its photocopies are safeguarded by glass in the museum. On the walls are photographs of many jatras celebrated in the Valley—especially in the Ason area. After reaching the main office area, Sumon points me to a shelf where various books on the history of the community are stored.

“Due to the nature of the house, we have a small museum. Even though we named it a museum, we prefer to call it a display of cultural collections,” she tells me. Not just collections, the museum is also trying to revive a dying cultural tradition called ‘Kumho Pyakhan’.

The dance, symbolising the protection of Nepal’s protector, Goddess Taleju, hasn’t been performed for almost four decades for several reasons. The Tuladhars of Ason and Kansakars of Janabaha perform this sacred dance with the main shows held at Hanuman Dhoka Durbar during the Mohani festival (coinciding with Dashain) in October. A Kumar (boy) dances as a band plays music using three-headed drums, cymbals and long horns.

This dance performed by Kumars was originally named ‘Kumar Pyakhan’, but later the name became ‘Kumho Pyakhan’. “Apart from storing cultural artefacts, we are trying to revive this dance,” says Sumon. “The Kumars participating in this ritual must follow strict rules like a Kumari. Parents these days prefer that their sons go to schools and get an education rather than be engaged to this dance form,” she adds. The museum is documenting this dance and trying to raise awareness.

At its opening in 2014, the museum received all kinds of donations, such as tools and clothes, from members of the community. Apart from these donations, the Udaaya Samaj searched for various types of jewellery and bought them to store at the museum.

Even in a limited space, this museum displays many elements of the Newa culture. From traditional dresses to almost obsolete utensils used in rituals, photographs of the area as old as the early 1900s, real ornaments used in dances such as ‘Kumo Pyakhan’, and everyday tools used by the nine Newa castes—this museum is a treasure for culture and history enthusiasts.

This century-old house portraying such rich Newa culture belonged to Laxmi Prabha Tuladhar and her husband, Harshsa Ratna Tuladhar. Upon their passing, the house’s ownership was transferred to three close relatives of Laxmi Prabha—Padma Jyoti Kansakar (industrialist and a former member of parliament), Roop Jyoti (former assistant finance minister and president of Udaaya Samaj since 2012), and Dan Ratna Tuladhar (businessman). The three owners legally donated the house to Udaaya Samaj in 2019, where the museum is built today.

“One of the many specialities of such traditional homes is their balconies,” says Pranidhi. Such balconies were designed to face the street, where various jatras could be viewed.

Sumon views these street-facing spaces as a commercial advantage. “During jatras, we can charge people a certain amount to book the balcony to experience festivals closely,” she says. However, as the museum lacks manpower, many such ideas are yet to be executed.

The indifference of local youths worries Sumon. She often requests the young people to come and work at the museum, but they never show up. “I guess they see my grey hair and think Udaaya Samaj is only for old adults,” she jokes. “If we had young faces working for us, we could attract more youths and teach them the importance of Newa culture and what we are doing here,” she says, emphasising that youth involvement is vital to revive a culture.

Lack of manpower isn’t the only challenge for the museum; low funds are also a worry. According to Sumon, many VIPs visit the museum, praise the work being done and leave without showing any support. “Even though I remind them of a donation box, they simply nod and walk away,” she says.

In 2015, when the devastating earthquake damaged the museum, paucity of funds proved to be especially worrisome. Luckily, the house donors stepped up and provided some funds to restore the house. The renovation, carried out by retaining the house’s essence, took six months. “We even repainted it with the same colour the original house owners had painted it with,” says Sumon.

Without adequate funding and a lack of manpower, the museum isn’t in a position to open every day of the week. Apart from specific timings on Tuesday and Thursday, on other days interested visitors need to call and make an appointment to tour the place. The museum doesn’t get many visitors.

“To attract people, we requested guides to bring tourists to the museum, but they don’t bat an eye to such a small establishment,” Sumon says. Additionally, the Nepal Tourism Board (NTB) mandates that licensed guides can only operate in designated areas and are prohibited from taking tourists elsewhere. “We tried to enlist our museum in the NTB’s guide list, but the process is tiresome,” she says.

Similarly, “the process of obtaining funds from the local ward office is also difficult,” says Pranidhi. The support is there, but the process of getting that aid is long.

“Our government needs to be more serious about heritage conservation. Due to natural calamities and other factors, we are losing such houses left and right. But dragging our feet puts our culture at risk,” Pranidhi says. “Even the specific style of maintaining such old houses is dying,” she adds.

The Udaaya Museum is a testament to the rich yet fading heritage of not just Udaaya Samaj but of the entire Newa community. Despite challenges like limited funds, lack of manpower, and dwindling youth interest, it remains a crucial space for cultural preservation.

Without urgent support from local bodies and the next generation, invaluable traditions and history may soon be lost. Recognition and protection of such cultural gems are a must before they become mere memories.

15.3°C Kathmandu

15.3°C Kathmandu