Entertainment

A celebration called Hare Rama Hare Krishna

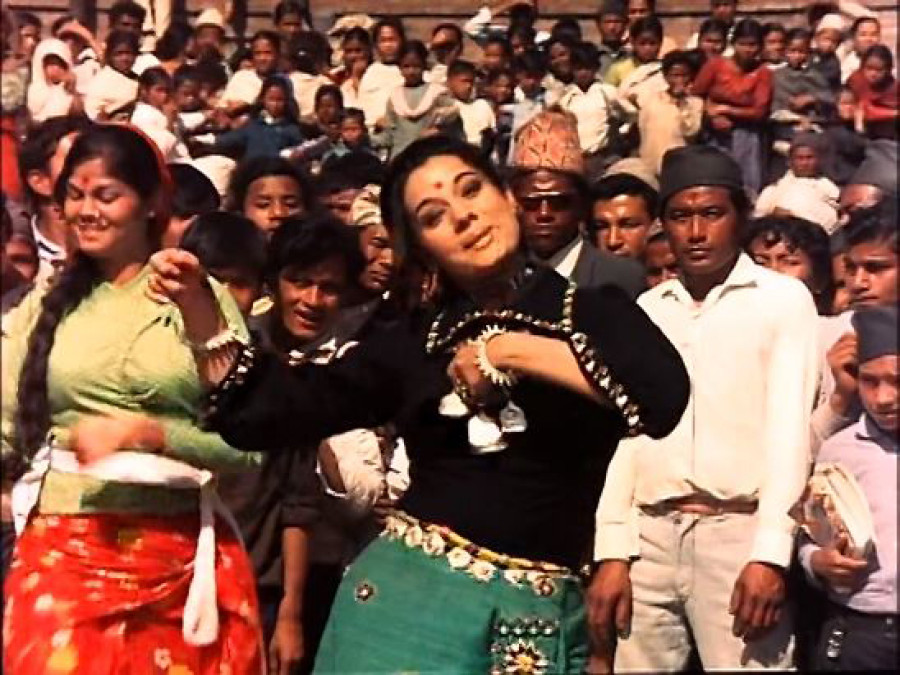

A psychedelic drone pierces through ancient Kasthamandap and out into Basantapur Durbar Square. From amidst long-haired, droopy-eyed hippies swaying wildly in the haze of hashish smoke, teenaged Zeenat Aman twirls her body to the hypnotic ‘Dum Maro Dum’—an image and tune etched in the memories of generations to come.

Prawash Gautam

A psychedelic drone pierces through ancient Kasthamandap and out into Basantapur Durbar Square. From amidst long-haired, droopy-eyed hippies swaying wildly in the haze of hashish smoke, teenaged Zeenat Aman twirls her body to the hypnotic ‘Dum Maro Dum’—an image and tune etched in the memories of generations to come.

Bollywood legend Dev Anand’s Hare Rama Hare Krishna—a story of how the hippie movement’s drug culture was destroying individuals and families—was an instant classic when it was released in 1971, with ‘Dum Maro Dum’ becoming its anthem.

Dev Anand with Zeenat Aman in 'Hare Rama Hare Krishna'. Photo Courtesy: Bimal Poudel Facebook

In his memoir, Romancing With Life, Dev Anand says that the shooting of ‘Dum Maro Dum’ occurred as “thousands of Nepalese people, who, having drunk their local brew, swayed to the rhythm of ‘Dum Maro Dum’, with a dozen guards of the royal mounted police keeping constant vigil lest a brawl broke out in the excitement of intoxication.”

Indeed, for the entire 10 weeks Dev Anand was shooting in Kathmandu, locals were gripped with Bollywood fever as Dev Anand, Mumtaz, Zeenat Aman, Prem Chopra and other stars paraded the gallies and courtyards. The film’s shooting was, in Dev Anand’s own words, “one big celebration”.

Dev Anand (right) with King Mahendra (left). Photo: Bimal Paudel Facebook

King Mahendra’s embrace

This was 70s Kathmandu, and such a spectacle could only take place because Hare Rama Hare Krishna won the heart of none other than King Mahendra.

In his memoir, Dev Anand says that in February 1970, he was attending Crown Prince Birendra’s wedding as a royal guest when, one evening, he chanced upon an Indian girl in the midst of hippies at The Bakery, an iconic hippie commune in Swayambhu. The next day, the actor met with the girl—Jasbir turned Janice—who’d run away from her family following her parents’ divorce in Canada, and finding solace in the carefree world of hippies, followed herself in Kathmandu.

“The moment she left, the story idea and Jasbir, its central character, had formed themselves in my mind,” Dev Anand recollects in the memoir. The film would be shot almost entirely in Kathmandu’s core historical sites. But to accomplish a shooting of such gigantic scale would’ve been impossible without the approval of the highest authority—the king.

Receiving Dev Anand in the visiting room of the Narayanhiti Royal Palace, King Mahendra not only approved of the new film concept graciously, but took a strong personal interest to see it develop instantly by inviting the actor to complete the script in Pokhara. Dev Anand recreates the conversation in his memoir:

‘Would you like to extend your stay and visit it [Pokhara]? It is very quiet and peaceful there, good for your type of work.’

‘I’d love that,’ I said.

“There is a very stylish hotel there, owned by my younger brother, Prince Basundhara, called The Fish Tail, against the backdrop of the majestic snow-capped Annapurna range. It will be ideal for your writing,’ King Mahendra said. “I shall give you an inspector of police as your bodyguard and guide, a real Gurkha. He will know where to take you, and when.”

According to the memoir, Dev Anand returned to Bombay with the script, and came back to Kathmandu with an 84-member shooting crew. King Mahendra had a cabinet minister partake in the film’s mahurat ceremony organised at Hotel Soaltee, writes Anand in his memoir. Energised by the king’s backing, Dev Anand, surrounded by hordes of Kathmandu locals, would work for the next 10 weeks creating magic.

A screen shot from 'Ghungroo Ka Bole'. Photo: Bimal Paudel Facebook

Bollywood magic in Kathmandu air

Author Peter J Karthak was 27 and working at Hotel Soaltee’s Casino Nepal when he first saw a film crew arrive on giant buses with camera sets, stands, generators, lighting equipment and large boxes containing other shooting equipment. Over the next few days, Karthak saw the cameramen, cast and crew going about as, Dev Anand, speaking a mix of Hindi and English, hollered instructions, waving his hand, his head tilted, a bright silk scarf tied around his neck, with a cap at a rakish angle—all in his iconic style.

“They really came like an expeditionary force,” says Karthak, now 75-years-old. “Just imagine the sizes of the equipment brought and the scale of logistics and challenges involved in transporting them from Bombay, whether they brought them by air or land. It was a colossal project. It was indeed magic unfolding for the people of Kathmandu.”

Nineteen-year-old Om Kaji Tamrakar, now 67, watched with awe from his home at Maru Tole as this grandeur of the Bollywood films he bunked classes to watch at Ranjana Hall descended upon the courtyards of Maru Tole and Jhochhen, transforming them into live stages for Bollywood’s biggest stars.

Hindi films had captured Kathmandu’s imagination ever since Janasewa Cinema Hall opened in New Road in 1949. It was followed by Ranjana Cinema Hall in 1956, and later Jai Nepal Hall and Bishwo Jyoti Hall in Kathmandu and Ashok Cinema in Patan. Just as these movie theatres initiated Kathmandu folks to Hindi films, Dev Anand was rising to stardom in Bollywood.

And so, by the time Dev Anand’s team arrived in Kathmandu, locals were familiar with his smile, his iconic movements and his trademark scarf and cap, says Tamrakar. Everyone had also heard, he says, that the actor had been banned from wearing black because his female fans were prone to fits of hysteria.

On the screens of Kathmandu’s cinema halls, locals had seen Bollywood dancing queen Mumtaz move her aquiline body in hit songs, like ‘Aajkal Tere Mere Pyar Ke Charche’; they knew Prem Chopra’s compelling villainous acting in films like Teesri Manzil and Woh Kaun Thi?, and Zeenat Aman from her films Hungama and Hulchul. Rajendra Nath and Junior Mehmood too were household names for their comic roles. So when these stars descended on Maru Tole, for Tamrakar and his community folks, it was as if a piece of Bombay itself had been plucked up and placed right there in their alleys.

“It was an unbelievable experience to see the stars in the flesh, and so many of them all at the same time. I saw Dev Anand, Junior Mehmood, Mumtaz, Zeenat Aman, Prem Chopra, Rajendra Nath and Iftekhar, it was dreamlike, it was magical,” says Tamrakar.

But away from the shooting, Kathmandu was also witnessing another side of the superstars. Karthak vividly recollects an intriguing private side to Dev Anand. “Every evening after shootings for the day were over, the moment the clock struck seven, Dev Anand would lean by the reception counter at Hotel Soaltee and dial a trunk call to India, to someone at Mehboob Studios in Bombay,” says Karthak.

Mehboob Studio, founded by director Mehboob Khan, was where Dev Anand shot large portions of his most acclaimed films, including Guide.

“He talked so loudly as he detailed what he’d accomplished that day. ‘Do you hear me?’ he’d shout, and then detail he did this and that,” Karthak recalls. An awestruck crowd of hotel staff and locals who’d managed to enter the premises would’ve formed around Dev Anand as he made that phone call.

“Kathmandu locals entered an euphoric mode of ‘Dev Anand is in town’, ‘let’s go see Dev Anand’ and wherever he went thither they followed,” says P Kharel, a film enthusiast who would later join The Rising Nepal English daily as its entertainment and sports reporter, and rise to become its chief editor. “Tea shops and bhattis, chowks and gallis, womenfolk in households, students in schools, everywhere, everybody had a story to tell about the events that transpired in the shooting spots.”

Apart from the celebrity presence in Kathmandu, what augmented this sense of celebration was that Kathmandu locals found themselves in a dream opportunity to be a part of the Bollywood screen, says Kharel.

Locals on the set

Indrachowk locals Ram Krishna Prajapati ‘Toofan’ and his brother Shyam Krishna Prajapati ‘Tarzan’ had long had acting ambitions and were even associated with the Rastriya Naachghar in Jamal.

“With their dandy looks and long, thick sidelocks which, much like Elvis Presley’s, fell all the way down to their chins, the brothers were both heroes of their toles,” says Karthak, who is the siblings’ brother-in-law. “Girls were always falling for their charms.”

Veteran actor Basundhara Bhusal too remembers the excitement at the Naachghar ever since word spread that Dev Anand was seeking actors from among Naachghar actors.

“There was an immense sense of excitement and competition among the actors to get selected,” she says. “Both Tarzan and Toofan, and everyone else selected were elated to be acting alongside the biggest Bollywood stars.”

Meena Singh, another famous Nepali actor, was selected by Dev Anand himself, who convinced her parents to allow her to play a role over dinner at the Soaltee Hotel.

“I often participated in musical and stage performances,” says Singh. “A while before Dev Anand came, I had led my alma mater Padma Kanya Campus at a grand inter-college opera competition at the Rastriya Naachghar. Our team emerged the winner and I was awarded medals and other prizes by the King and Queen in a grand ceremony. This made me really popular at Padma Kanya and a favourite of our principal Angur Baba Joshi. Perhaps this was why she mentioned me when Dev Anand asked her for recommendations.”

In the film, Toofan plays Dronacharya’s (Prem Chopra) aide, and Tarzan the manager of Dronacharya’s carpet factory. Singh, along with other local actors Prashant Rana, Deepak Rana, Rabi Shah, and Gerda Anita Weise, a Swiss national who grew up in Kathmandu, would be Jasbir’s [Zeenat Aman] hippie friends. Other actors included actor-director Prakash Thapa, Narayan Krishna Shrestha, and several others in the film’s dance sequences.

For these actors, not only was it a lifetime opportunity to work with Bollywood stars, but also to bond with them, something they would cherish not only during the shooting period but would carry memories of for the rest of their lives.

Prashant Rana in between Gerda Anita Weise (Left) and Zeenat Aman. Photo Courtesy: Bimal Paudel Facebook

Singh says that although she was never interested in acting in films, and her performance in Hare Rama Hare Krishna and in a few other Nepali films happened by chance, being on the sets alongside Dev Anand and interacting with them was a lifetime opportunity for her and other actorss.

“All of us rejoiced being on the sets with the stars. Moreover, the local actors and the stars developed a strong bond,” she says. “Dev Anand and Zeenat Aman were both very friendly. Dev always called everyone by their names, and the Nepalis and Zeenat Aman talked for hours behind the sets.”

Another actor, Gerda Anita Weise recalls being touched by how compassionate Dev Anand was: “I had a great time shooting and Dev Anand was the most wonderful human being you could imagine,” she says. “A great loving person with a big heart, just someone so special. All others were great and fun, but Dev really was special.”

This relationship between the locals and Dev Anand was seemingly cemented when Anand decided to adopt some of their names for the film’s lead characters.

“Dev Anand took the name Prashant for his character because he loved the name of one of the actors, Prashant Rana. Also, Gautam Sarin’s character took his name from Deepak Rana, and Rajendra Nath’s character is called Toofan,” Singh says.

Spectacle in the day, spectacle at night

For the entire eight days of the shooting of the infamous ‘Dum Maro Dum’ song in Kasthamandap, Om Kaji Tamrakar made sure to stick around his home so he could secure a good spot that offered a clear view of the shooting.

“The roads, balconies and roofs around Kasthamandap were overflowing with people, with everyone shoving and pushing to get a glimpse of the shooting,” he says. “Bright shooting lights were cast into the sky, making it seem like the night above Basantapur had been transformed into broad day. Kasthamandap was designed into a restaurant setting and hippies smoked and moved their bodies wildly, dancing a dance we’d never seen before.”

As Tamrakar craned his neck for a good view, Zeenat Aman took drags from a chillum and shook her body. With cameras rolling, Dev Anand would move around yelling ‘cut’ intermittently. The song ‘Dum Maro Dum’ resounded through Kasthamandap and Basantapur, and the gathered crowd erupted into cheers, singing along every time the chorus ‘Hare Krishna Hare Rama’ came.”

And it wasn’t just Basantapur where the crowds gathered. Major shooting spots like Swayambhu, Jawalakhel and Bhaktapur drew throngs of people. Dev Anand’s description of the crowd that had formed to see the shooting of the song ‘Ghungroo Ka Bole’ at Nyatapola best evokes the frenzy: “[P]eople came out in full force to participate in a dance number by Mumtaz, shot at its main square. It was as if the whole township was on a mission. All the housewives from their homes, kids from their schools, and men and women from their work, from wherever their offices or workplaces were, were on a holiday with Mumtaz, as she danced her way through their hearts, for three successive days, with the sun shining in benevolent warmth on all those whose spirits were enlivened and their joy unlimited.”

The crowds were so big that the government needed to deploy a fair number of police personnel for security, says Bindu Prasad Upadhyay Dhungel, a former DSP of the Nepal Police who was then an inspector deployed to the scene. “Not only was it important to not disturb the shooting, but also to prevent rowdy members of the crowd from getting too close to the actors and touching them inappropriately,” says 83-year-old Upadhyay Dhungel.

The crowd once became so big in Pako, New Road that quick-thinking locals had to form a human chain to protect Mumtaz from those trying to touch her inappropriately, recalls Prem Krishna Shahi, 61.

During the shooting of ‘Dum Maro Dum’, the police even had to baton charge the crowd.

“Using batons, the police chased us from Kasthamandap to Chikan Mangal,” says Tamrakar. “But like most, I went back again. It wasn’t just a jatra that we could’ve seen again the next year, it was Dev Anand shooting in Kasthamandap.”

As it happened, it wasn’t just locals like Tamrakar who revelled at the sights. Anand’s memoir reports that Nepal’s royal family not only participated in the celebrations but also provided crucial assistance to ensure the film’s success.

Prem Chopra and local actor Ram Krishna Prajapati ‘Toofan’ during the shooting in Bhaktapur Durbar Square in the foreground while other local actors seated alongside Zeenat Aman in the background—Meena Singh and Deepak Rana (both garlanded) in the extreme left. Photo Courtesy: Bimal Paudel/Facebook

A royal in the crowd

Although Dev Anand doesn’t mention it directly, King Mahendra most likely kept himself informed about the film shooting. Two incidents, both concerning then prince Gyanendra, attests to the royal family’s direct interest.

“One day, I spotted a young man, standing on a platform alone in a corner, looking at the magic being captured by the movie camera,” Dev Anand writes in his memoir. “Someone came and whispered into my ears that it was the young Prince Gyanendra. I walked up to him, to invite him to come behind the cameras to witness the filming from up close. But he insisted on not creating a disturbance, and preferred standing aloof, all by himself.”

Coincidentally, the same day, Dev Anand happened to leave his script at a shooting spot on a hillock, where he had flown to on a helicopter. So, the only way to retrieve it before it was lost was again by helicopter. Having failed to arrange a chopper, Anand, in a moment of panic and uncertainty, decided to contact the prince.

“Prince Gyanendra came to my mind, for the only other helicopter in Kathmandu belonged to the king,” he writes. “The palace could come to my rescue. I called the secretary on duty there and explained my predicament. In a matter of minutes the royal helicopter was ready for me, thanks to the courtesy extended by Prince Gyanendra.”

Inspirations and celebrations

Perhaps it was due to the royal family’s backing and the pervasive celebratory spirit that Dev Anand was able to swiftly dissuade a quiet discontent that had risen about the shooting in Kasthamandap.

‘Dum Maro Dum’ involved a lot of smoking, wild dancing, even kissing. Some community members saw all this happening at Kasthamandap, a religious site, as clear acts of blasphemy,” says Dhungel.

The Rising Nepal, in an editorial, alleged desecration. Writing of this in an article in The Times of India in 2011, Indian journalist Jug Suraiya says that The Rising Nepal “accused the actor-director of having desecrated the Kashtmandap (sic). A fire-and-brimstone editorial likened Dev Saheb to a latter-day Mohammad Ghazni.”

Dev Anand immediately organised a press conference, says Suraiya, and that the “Nepali journalists soon thawed to Dev Saheb’s sunshine smile” and that “next day’s headlines transformed Dev Saheb from heel back to hero”.

In the end, all that was in store for Dev Anand was inspiration from the consuming celebratory mood around him. In Romancing with Life, he writes: “Indeed the entire filming was like one big celebration…I worked three shifts a day like an inspired man, working in the morning, afternoon and at night, depending on the requirements of the scenes, shooting day for day, night for night.”

Inspired, Dev Anand directed his cameramen to zoom in on not only Kathmandu’s swathes of green paddy fields, its characteristic mud-brick houses, its lanes, idyllic hills and its historical landmarks, but also the colourful people that had gathered to simply revel in his shootings. This was Kathmandu in its natural form—smiling faces of little Tibetan children throwing woollen balls at Dev Anand; a young local man smiling as Dev Anand shouts at Mumtaz in the Nyatapola courtyard; an elderly man sitting in a falchha with a walking stick for a flickering role where Mumtaz teasingly takes his arm in the song ‘Ghungroo Ka Bole’.

crowd gathered at the Nyatapola temple to see the shooting of the song ‘Ghungroo Ka Bole’. Photo Courtesy: Bimal Paudel/Facebook

Anand’s gratitude became more visible in the dedication at the beginning of the film: “To the people of Nepal”. He seemingly took to heart the love he received from Nepal as he would return in 1974 to shoot Ishq Ishq Ishq.

But as Dev Anand’s crew left Kathmandu, the celebrations did not end yet.

When the film was released in 1971, Kathmandu relived the celebration. Crowds got so large at Jai Nepal Hall, where it was first shown, that a tradition followed by Kathmandu’s cinema halls was broken, states writer Suresh Kiran in his article “Kasthamandap ma Dev Anand: Maru tole ma Dum Maro Dum” published in the Annapurna Post daily in 2017. “The film was shown in Ashok Cinema Hall shortly after it started in Jai Nepal Hall,” he writes. “A film shown in one hall wasn’t shown in another hall then, but Hare Rama Hare Krishna broke that record.”

On screen, Kathmandu had multiple reasons to be awed.

Tamrakar describes the sense of awe and bewilderment among residents uninitiated to the intricacies involving the editing process, caught by surprise, as they saw that a character that runs from Swayambhu emerges in the courtyard of Bhaktapur, or when other seemingly disparate scenes appeared together.

Bigger excitement lay in seeing Kathmandu locals in the screen. “People cheered each time local actors appeared on screen,” says Tamrakar. “Like in the scene where the camera zooms in on Toofaan cha in ‘Dum Maro Dum’.”

But nothing suggests the shooting’s enduring impact on Kathmandu’s psyche than how its memories have lived on through the generations, especially in those from Maru Tole, Jhochhen and other shooting spots, says Suresh Kiran, who grew up in Jhochhen listening to these tales.

“Even today, whenever this film is mentioned, the elderly say, ‘Oh, that film was shot in our Maru Tole,’” says Kiran. “Those who saw the shootings never really stopped talking about them.”

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu