Entertainment

Aftershock: A Labour of Love

Pooja Pant, one of the producers of the Netflix documentary miniseries ‘Aftershock’ based on Nepal’s 2015 earthquakes, has been using the visual medium for activism for two decades now.

Pinki Sris Rana

Back in 2001 when Pooja Pant went to a camera auction with her friend in the United States, she held a photo camera for the first time. Being an activist and a creative person, Pant was in constant search to merge a medium that combined both of her persona and that day when she held the camera, she found exactly that. And that medium took her deep into the world of videography.

After a year, Pant moved to the UK and there she got the chance of working on documentary filmmaking, she, right then, realised the power of the visual medium.

“We were working on the gap that existed among the first-generation Nepali migrants in the UK and the second-generation migrants. When we showed testimonial videos of the struggles of the older generation, the younger generation understood their struggles, which they had long forgotten. That is when my interest started growing in films as a tool,” remembers the 44-year-old.

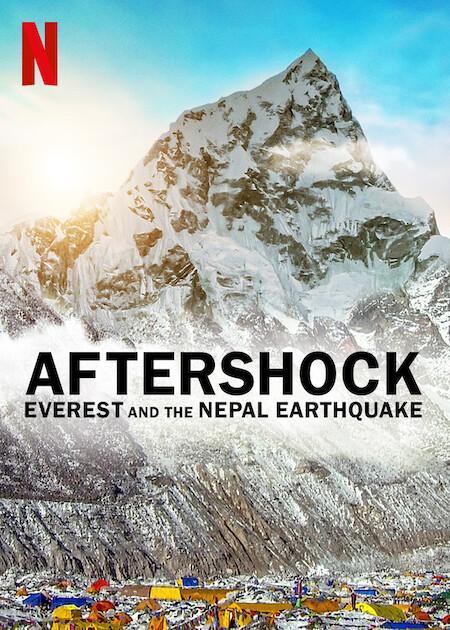

Pant, who has been using the visual medium as a further extension of activism and documentation purposes, is one of the producers of the Netflix documentary miniseries ‘Aftershock’ released on October 6.

In this interview with the Post’s Pinki Sris Rana, Pant shares her experience of working for a platform like Netflix, her responsibilities and challenges as a producer and more on the documentary itself.

Excerpts:

What was it like collaborating with international filmmakers and a platform like Netflix?

It was an exciting experience. One thing I absolutely loved the most about working with international filmmakers was the level of professionalism they had. When there are professional qualities in people you work with, the work becomes a lot easier.

It was a learning experience as well. Our director Olly Lambert had knowledge about the technical aspects of filming as well as the importance of the story. And not many directors have both qualities. He was very precise about what he wanted and he knew how to make his vision come to reality. So, there was a lot to learn from him.

As a producer, what was your role in the making of ‘Aftershock’?

I got associated with the project as a producer. And because it is a documentary based on Nepal targeted at not just Western audiences but Nepali as well, researching about the characters, locating them, building a relationship with them and bringing the nuances, were all part of my job. Director Olly and the producer, Tamar Lawson, came to Nepal for the shoot for six weeks, but the entire production took us 18 months.

The characters in the documentary ‘Aftershock’ are quite unique and interesting. You must have done extensive research to find such characters. Would you explain the process, please?

We actually interviewed 55 people in total for this documentary. We hadn’t finalised which survivor stories we would focus on initially. But after going through those 55 interviews, we decided to stick with the ones that intersected with the flow of our story. Our director knew exactly what he wanted and that precision made it easier to bring out such unique stories of the earthquake survivors.

Researching and locating characters was quite a challenging thing to be done during a time when the country was under a complete lockdown due to Covid. And then building a relationship with the characters to the point they were comfortable to be vulnerable and share their stories with you was another process in itself. In the 18 months of pre-production work, I was constantly in touch with them, doing everything possible to make the bond stronger. After all, the character is the god while filming.

Talking about the collection of footage of the 2015 earthquakes, it’s quite commendable what the team has been able to gather from the survivors. How challenging was that?

We had a designated online team that was solely focused on collecting the footage of the disaster. We even found some of the characters like Gopal through the online team.

The districts most hit by the 2015 earthquakes were Gorkha, Sindhupalchok, Dolakha, Dhading and Nuwakot. But the documentary is focussed mainly on Mt Everest, Langtang and Kathmandu, why?

Everest is definitely saleable, yes. But we stuck with the locations that brought out the most in the story. Initially, we had also researched about Dhading and we had some stories from there too. But rather than focusing on the locations, story was our main priority.

Do you think a documentary of this scale and quality would have been possible had a major platform like Netflix not been associated with it?

An affirmative no. The level of research that was done to make this documentary, the production value, we had to make a stage, the stock footage and the money paid to acquire them—everything costs a fortune. Without having a platform like Netflix, making this documentary wouldn’t have been possible.

Don’t you think the release of the documentary can impact Nepal’s tourism sector a bit negatively because of the terror of the disaster?

I got the same question a day earlier but I think it’s important to realise that a disaster of such a scale does not just happen. It comes every hundred years or so. The terror is definitely there seeing the firsthand footage of the earthquake itself, but I don’t think it will logically stop people from wanting to visit Nepal.

Why was it important for you to work on this documentary?

As a filmmaker, it is important for us to work on films. And to get a platform like Netflix and a film that was about the disaster that happened in Nepal, an experience I, too, shared with the survivors, was important because it inevitably needed a Nepali voice as well. A platform of such scale could definitely use a Nepali voice. And to be able to do that through my role as a producer makes me feel accomplished. My team was also very supportive. They acknowledged my opinion. Essentially, it was a film made for Nepali people as much as it was for the Western audience.

16.16°C Kathmandu

16.16°C Kathmandu