Entertainment

Preserving tunes and melodies for the posterity

Started in 2021, Nepal Music Archive aims to digitise the whole of Nepal’s music scene—songs, album covers, and articles—some dating as far as the 1950s.

Anweiti Upadhyay

From the haunting melodies of the Gandharvas to the rhythmic beats of the Tamangs, Nepal’s musical symphony ties together diverse traditions, carrying stories that intertwine with the history, cultures and traditions of the people who sing them. Among them lie tunes by icons like Narayan Gopal and Aruna Lama that have shaped eras and left indelible marks.

While these cherished recordings remain etched in our collective memory, we must all confront a sombre truth: some of the musical treasures these maestros left behind and much of Nepal’s musical heritage have already been lost to the sands of time. As cassette players faded into obscurity and the digital age took hold, some recordings, perhaps etched onto brittle tapes or deteriorating reels, were lost forever, leaving gaps in our musical legacy.

But there is hope. The Nepal Music Archive (NMA) stands as a shield against this loss. NMA is a digital archive that records everything they can find on Nepali music—from audio and video to books, magazine articles and research papers. It is an extension of the annual Echoes in the Valley (EITV) music festival, with pretty much the same team handling both these projects.

EITV is a grassroots festival that began in 2017 and focuses on traditional indigenous music. Started by Kanta Dab Dab’s bass player Riju Tuladhar and Bhushan Shilpakar, NMA has the patronage of prominent names in the music industry, like the bands Night and Kutumba, and musician and ethnomusicologist Rajan Shrestha, who goes by his alias ‘Phatcowlee’ for solo music projects.

The festival has been running every year since its conception, with numerous concerts, confluences and exhibitions which the organising team realised needed archiving. Notably, Shilpakar, drawing from his extensive work at Photo.circle and Nepal Picture Library, spearheaded the creation of this archive. After years of musing and planning, NMA finally started in November 2021, despite limited resources.

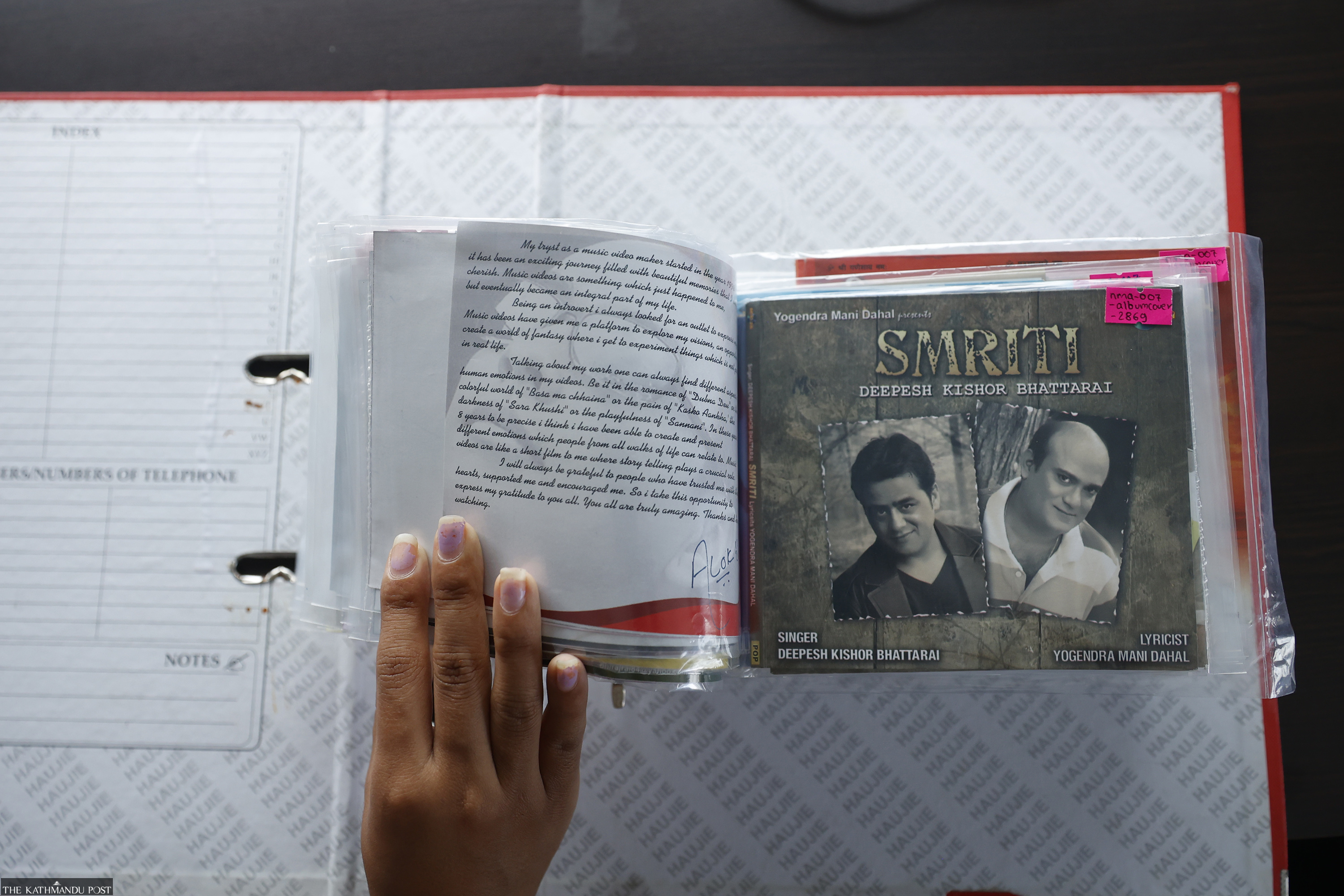

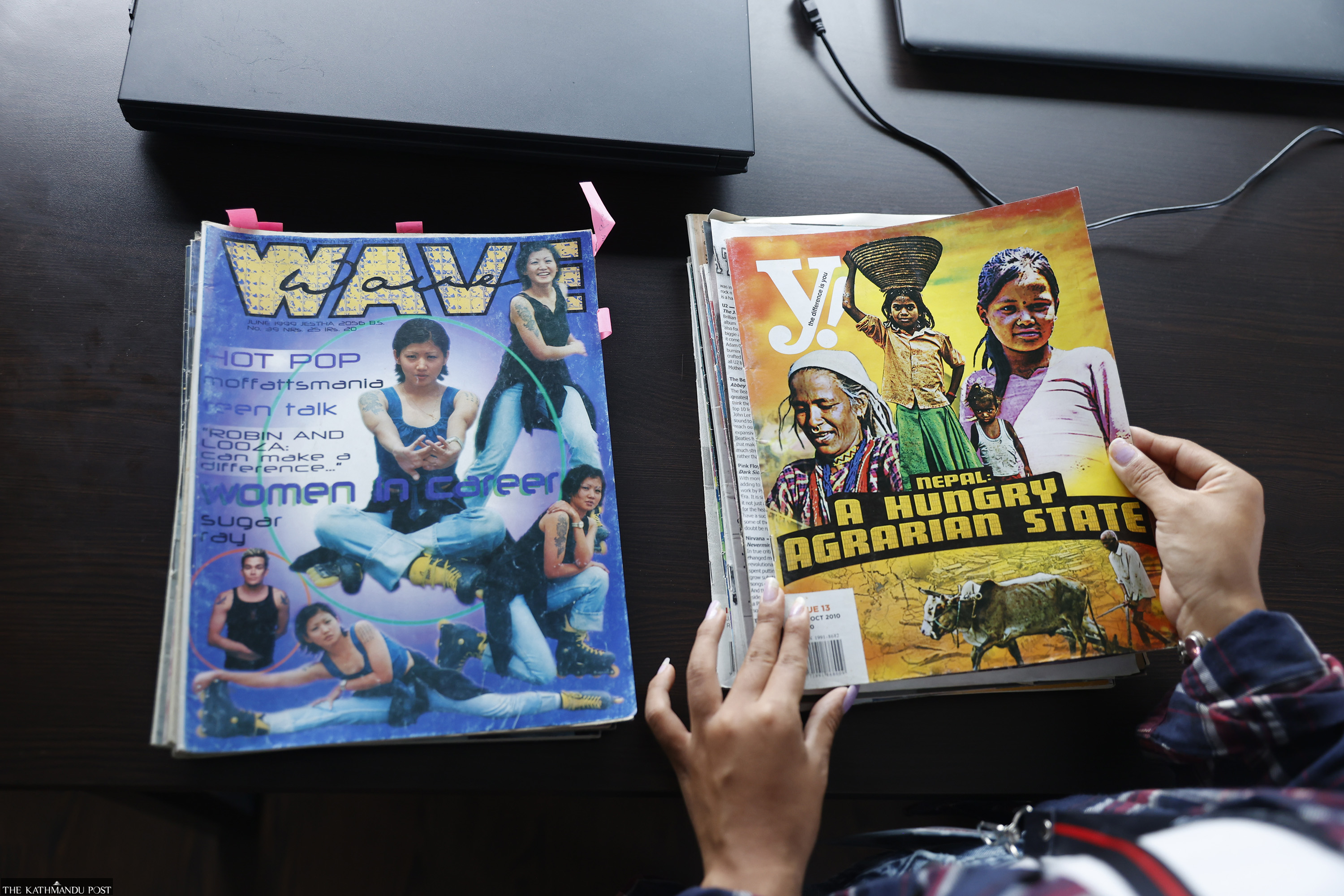

In the humble, one-room space NMA has in Bhotahiti—on the fifth floor of Tuladhar’s house—Jiwan Thapa Magar and Rojina Tamang work tirelessly digitising acquired collections, which range from audio, video, album covers to magazine clippings and books. Thapa Magar, a musician and ethnomusicologist currently doing a master’s in the subject at Kathmandu University’s (KU) Department of Music, is the digital assets manager who overlooks audio archiving. Tamang, pursuing a bachelor’s in computer science, is responsible for archiving graphics and texts. She also handles administrative tasks.

Thapa Magar and Tamang joined the archive in late 2021 and worked with other archivists, researchers, and interns on digitising collections, benefiting from their backgrounds in ethnomusicology and deep understanding of Nepali music. Unfortunately, due to financial limitations, NMA recently underwent a team downsizing, leaving Thapa Magar and Tamang as the sole staff members today.

Shilpakar, who manages most things in NMA, including the finances, is currently based in Germany and trying to bring the Gert-Matthias Wegner collection to Nepal. Wegner is a German ethnomusicologist and drummer who founded KU’s Department of Music and has extensively researched the North Indian and Newa musical traditions.

Until now, NMA has digitised more than 2,000 album covers, 400 cassettes, 200 books, 70 CDs, and 40 vinyls from around 30 contributors into over 3,000 archives.

The initial batch of around 300 tapes digitised by NMA came from the Madan Puraskar Pustakalya (MPP)’s collection. MPP had begun audio archiving some years ago but abandoned the project after the 2015 earthquake. Additionally, NMA has archived and catalogued music content—mostly cassettes, CDs and books—from various libraries across Kathmandu.

Shrestha and Shilpakar source music collections from collectors, often people they know within the music industry, and then bring these materials to NMA for archiving.

Sometimes, they encounter collectors during their research endeavours. While researching ‘Women in Music’, an initiative started by a former staffer, Appeal Poudel, to spotlight female musicians whose contributions to the Nepali music scene (who remain somewhat obscured in the mainstream patriarchal narrative of musical history), the NMA team came across the popular folk singer Hari Devi Koirala who was also associated with the Nepal Academy of Music and Drama. “She is an archivist, keeping old newspaper clippings that feature her and noting dates of awards and honours she received. So, we gathered a wealth of materials from her,” says Shrestha.

Once acquired collections reach the NMA office, Tamang and Thapa Magar begin their work. “It’s hard to predict how long it takes to digitise a single collection,” notes Thapa Magar. Sometimes, it’s smooth sailing—just pop out the cassette, digitise it, and save it on the computer. But more often, things aren’t that simple.

Due to their prolonged storage, these items—mainly cassettes and CDs—often gather dust and grime. Thapa Magar carefully cleans them and leaves them in the sun to dry (if that method suits the specific device). The same care goes into handling vinyl records. When he encounters items affected by mould, he stashes them in an airtight container with silica gel packets. “At the time, I feel like I’m roleplaying a lab scientist,” he jests.

As for the books, Tamang scans the covers and adds the metadata to NMA’s catalogue—making sure that the future retrieval of stored data is systematic and convenient. Some books have been donated to the archive and can be borrowed from their premises.

A recurring challenge NMA faces during digitisation is the availability (or lack thereof) of digitisation equipment. A recent example is musician Subi Shah’s vinyl collection, currently under the care of his son. Shrestha stumbled upon these while assisting Anna Stirr, a professor from the University of Hawaii-Manoa, in her research on Shah’s music. They enlisted the help of Pradeep Upadhyay, one of the first sound engineers in Nepal. “It took over three months because Upadhyay is older and unwell,” shares Shrestha. He adds that experts with knowledge of older devices are ageing, and younger generations do not know how to use them. So, without timely digitisation, we risk losing precious work, he laments.

“We just finished documenting over 2,000 album covers and posters designed by Anil Sthapit and have immediately started on Mukti Kunwar’s works,” says Tamang. The team believes archiving isn’t just documenting and digitising. While those are essential steps in the process, he states that the metadata adds depth to digital archiving.

NMA covers all the basics in metadata, including collector and artist names, publication years, and more. Plus, they’ve gone the extra mile by adding further details that will be valuable for researchers and fellow ethnomusicologists.

“Archiving is just the beginning,” he points out, highlighting their aim to make their work accessible. NMA’s website is public, but the digitised database, where all the digitised information is stored, isn’t. However, they plan to publicise it by the end of 2023. But Shrestha isn’t sure if that will actually happen, as the team is still debating if they have substantial information to put out there.

Another thing NMA is working on before going public with its database is the copyrights. NMA doesn’t keep physical copies of (most) CDs and books; they keep a digital copy which Shrestha notes is permissible for a public library/archive like theirs. The catalogue with the metadata will be available online, with information on where researchers can access those items.

“If you want to listen to a song but don’t need a physical or digital copy of it, you can drop by NMA and play it on our computer,” says Shrestha. However, if someone wants an actual copy, whether, for personal or commercial use, NMA can connect you with the copyright holder.

The archive is also creating a timeline that details parallel musical and related events that have happened worldwide. For instance, if a Nepali female artist released a Dohori album in 1990, the timeline would reveal global and Nepali happenings in that same month—music trends, political movements, and more. “This context will make it easier for researchers to draw conclusions,” says Shrestha.

Although NMA is possibly the first public music archiving project, it isn’t the only music archive in Nepal. Tribhuvan University (TU) and KU’s music departments have their own set of physical music archives. Radio Nepal also has an extensive archive. But the problem with these archives is that they aren’t really accessible to the public, says Shrestha. “Only students studying music at TU and KU ever really look for the musical archive at these universities’ libraries—even then, hardly anyone else knows they even exist,” he says. Moreover, Radio Nepal’s archive rests within the confines of Singha Durbar—a notoriously tricky place to enter.

Tamang suggests the scarcity of resources might be why nobody else took up the music archiving mantle. “Running an archive demands plenty of resources and money. A team of skilled individuals is essential too. So, it’s no simple task,” she reflects.

Thapa Magar, on the other hand, highlights Nepal’s lack of an archiving culture, “While we [Nepalis] did set up museums and libraries at some point, archiving music probably didn’t cross our minds,” he says.

Music, without a doubt, echoes the political, cultural, and social circumstances of their times, offering a parallel narrative of the nation’s journey. And Shrestha views musical archiving, which has finally found footing in Nepal in a positive light. “Of course, we’ve lost a lot of information. But it’s good that we’ve started,” he says.

22.64°C Kathmandu

22.64°C Kathmandu