Arts

The highs and lows of Kathmandu Triennale

As Kathmandu Triennale 2077, Nepal's biggest art event, is set to conclude in a week, the Post reviews what worked and what didn't.

Ankit Khadgi

In recent years in the field of arts, there has been steep growth in the discourses around decolonisation. Throughout history, it's mainly the Western canons that have shaped the common understanding of arts. As a result, there has been a systematic exclusion of indigenous artworks in the contemporary art world.

Thus, to dismantle the preconceived notions attached to the realm of art and to redefine art’s meaning beyond the colonial gaze and Eurocentric understanding, many artists, curators, and institutions around the globe have been relying on indigenous ways of expression and creativity, exhibiting them in various shows and art spaces.

Kathmandu Triennale 2077—championing the very thought of decolonising the art movement and giving space to diverse forms of indigenous arts—is featuring more than 300 artworks from 130 artists from Nepal and across the globe. The works are exhibited in five different venues.

At this year's Triennale, which is in its second iteration, one can find diverse artworks that offer different perspectives to the visitors. In all five venues, different mediums of expression like photos, paintings, installations, films, and mix-media works are placed with meticulously written statements that help us understand the context of the artworks.

Most of the creations differ in storytelling, presentation, and medium. They also explore themes like exploring human sexuality, queering the human bodies, indigenous expressions, folklore, and using artworks as resistance against colonial forces.

Out of the five venues that are part of this year's Triennale, whose artistic director is Cosmin Costinas with Sharareh Bajracharya leading the team as the director, Nepal Art Council (NAC) features the most impactful exhibits, and the venue's artworks manage to evoke all kinds of emotions among viewers.

Sheelasha Rajabhandari and Hitman Gurung, the co-curators of the Triennale, have wholly transformed NAC from a white-cube plain, almost dull gallery to a vibrant place where people can learn about many things and expand their worldviews.

In the ground floor's first room to the right, Rajbhandari and Gurung have strategically placed one of the most significant artworks of the entire exhibition--'A Woman Was Harassed Here'. Created by Aqua Thami, an indigenous artist from India, the artworks highlight the lack of safe space for women in any corner of the world.

Thami's video highlights how we, as a society, have always remained silent about the absence of safe spaces for women. In the same room, several pink posters placed on a desk with the line 'A Woman was Harassed Here', written in both Nepali and English, send a powerful message. Through the posters–which the viewers are allowed to take home–Thami reminds us how there's no space left in the world where women haven't been harassed.

The walls where Thami's works are kept are also adorned with pink notes, and written on them are harassment stories shared by the gallery's visitors. With its powerful message and interactive and participatory setting, Thami's work stands out the most and makes us uncomfortable and forces us to think.

However, had the curators pasted the posters on public walls in the Valley, Thami's work would have reached a much broader audience and incited more conversations around the pertinent issue of safe spaces.

Another equally evocative work exhibited in the same room is Andrew Thomas Huang's semi-autobiographical 2019 short film 'Kiss of Rabbit God'. Huang's sexual awakening tale of an Asian-American restaurant worker seduces us and holds our attention throughout its 14-minute screen time.

The deftly made short film, which takes influence from Chinese folklore, is a queer film in its truest sense as the filmmaker experiments with the visuals and storytelling instead of following the norms of filmmaking.

Writer and activist Indu Tharu's revolutionary poem, 'Ragat Timro Pani Rato Cha'; Nagendra Gurung's photo series, 'Chalis Katesi Ramaula'; and Karan Shrestha's photo series, 'Waiting for Nepal' are also some extraordinary works that shouldn't be missed.

But a few of the exhibition's artworks at NAC feel out of place. For instance, one can argue that Shashi Bikram Shah and Arhant Shrestha's works don't deserve space as the ethos of their works don't align with Triennale's overall objectives and values.

While Shah's artwork feels like a tribute to Nepal's monarchical system (a system built on the indigenous community's oppression), Shrestha's works appear as nothing more than a depiction of his rich and comfortable life. Their works come from a place of privilege, and it doesn't make sense why the organisers decided to give them space in the exhibition.

Since NAC features artworks of several artists, the venue appears overcrowded. As the viewers are obliged to actively use their senses to see, read, and listen to the exhibits, it takes a lot of energy, dedication, and patience to fully comprehend the works, which can sometimes be mentally and emotionally taxing.

However, things are strikingly different at Siddhartha Art Gallery (SAG), another venue of this year's Triennale. Featuring artworks of just four artists, SAG, owned by Sangeeta Thapa, who's also the chairperson and founder of Triennale, doesn't feel crowded.

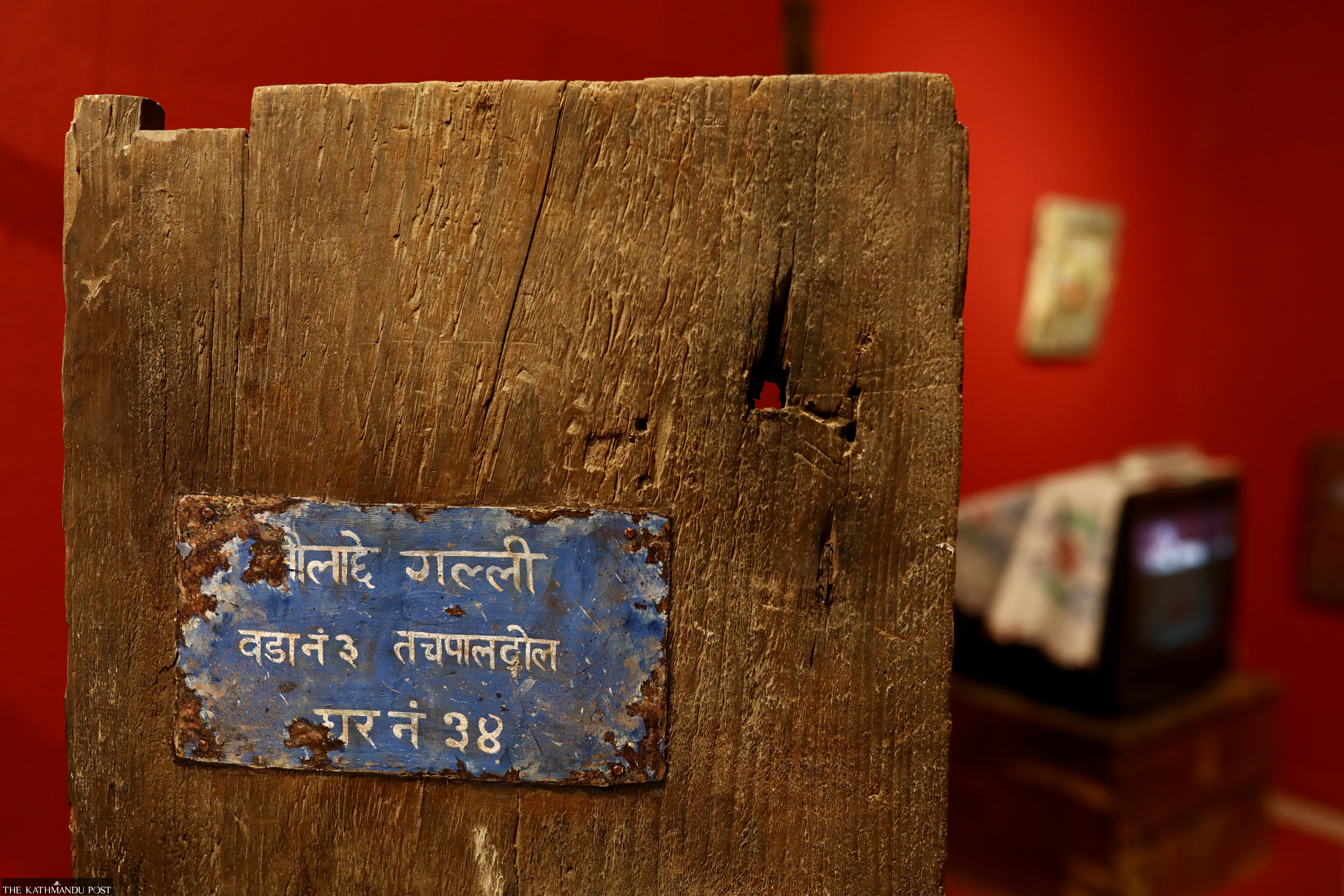

Hitesh Vaidya's mix-media work, 'Recollecting Memories', a deeply personal body of work, is the most captivating out of the four artists’ works.

In 'Recollecting Memories', Vaidya has painted small details such as the routine of load shedding, which people relied to keep track of power outages when Nepal was reeling under hours of power outages, light switches and artefacts that he collected from his ancestral house when it was destroyed in the 2015 earthquake. His works take us on a nostalgic journey and remind us of our own memories of bygone days.

Other artworks on display in other venues also evoke such feelings of familiarity.

For instance, Chet Kumari Chitrakar's artworks exhibited in Keshav Narayan Chowk of Patan Museum are something we have seen before but haven't paid much attention to.

Her artworks, which consist of images of gods and goddesses glued on the doorways of houses in Kathmandu on occasions of religious festivals like Naag Panchami, allow us to expand our vocabulary of art.

Instead of just placing the images on a table, the curators could have pasted them on walls or a replica of a doorway. But by featuring Chitrakar's artworks, Triennale forces us to rethink our definition of art and how exhibitions have systematically excluded works like these.

The same reasoning allows Bhakta Bahadur Sarki's 'Mukhiya ra Mukhiyani' and 'Bagha' to stand out among the artworks exhibited in the venue. The wooden sculptures of protective figures that Sarki, a native of Jumla, has created are often kept in the villages in the Karnali region to protect residents from evil spirits, and many do not consider them as works of art.

However, the exhibitions at Taragaon Museum and Bahadur Shah Baithak aren't as engaging as the other three venues.

Perhaps that's because both of these locations have grand architecture and are works of art in themselves, thus making it easy for one to get distracted while looking at the exhibits. Yet a few artworks shine due to their sheer beauty and thoughtfulness.

At Taragaon Museum, Sunita Maharjan's two installations, 'Above the Earth, Beneath the Sky' and 'Act of Finding Line', are creative and push the boundaries of art.

In 'Above the Earth, Beneath the Sky', wheat stalks are kept on iron pillars that protrude from the ground. Through this placement, Maharjan depicts the paradoxical reality of how alienated Kathmandu residents have become with farming.

'Act of Finding Line', a two-minute-long video, is based on a similar theme and is equally provocative. Although the video, which features the artist conversing with nature while planting rice saplings, doesn't offer any new or exciting visuals, it still gives the viewers a sense of fulfilment.

Meanwhile, at Bahadur Shah Baithak, Uma Shankar Shah's 'Railways Station of Janakpur' and 'NJJR', both of which were created in 2016, leave an everlasting impact. Even though his two works have already been exhibited in other art exhibitions, they still feel fresh to look at because of the vibrancy and the fine details.

In his works, Uma depicts the role Nepal Janakpur Jayanagar Railway (NJJR) has played in strengthening the ties between Madhesis and Indians and how the infrastructural development led to the exchange of culture and arts between the two neighbours.

The artworks exhibited in these two venues offer visitors ample opportunities to learn about people's cultural practices.

But overall, there are many areas where Triennale could have done things differently.

The number of international artists participating in the exhibition outnumber their Nepali counterparts. Thus in many instances, the works of international artists take away a lot of space, due to which the works of the local artists get lost in the crowd.

The purple background, which is omnipresent in all the venues, is too jarring to eyes at times, especially in locations where the artworks do not contrast with the backdrop. Even though it's understandable why the organisers used the purple background in all the venues (a famous paint company whose brand colour is purple is funding them), the brand placement should have been integrated seamlessly rather than being so obvious.

It's also important to reflect on how accessible the Triennale is for the general crowd, whose works and knowledge the organisers are celebrating. Almost all the venues of this year's Triennale are museums and white-cube galleries. Such venues have always been more accessible to the English-speaking Nepali elites than the general public.

An argument can be made that all the venues are free to visit except Patan Museum, where visitors need to pay a nominal fee of Rs 30. But will the general public feel comfortable in a space where they can't read the statements that are written in highly sophisticated sentences filled with jargon and heavy adjectives and verbs in both English and Nepali? Perhaps not.

Therefore, the organisers needed to be considerate enough and display a few artworks in open spaces with simple art statements to make the experience of Triennale more accessible to a larger audience.

Hopefully, the next edition takes accessibility into consideration because the kind of works that are usually displayed at Triennale deserves a wide viewing.

22.64°C Kathmandu

22.64°C Kathmandu