Arts

Bilampau: The forgotten stories of Nepali art

What does it mean to remember an art form? How can we revive a dying art form into the collective consciousness of the twenty-first century?

Angie Ling

Within the rich heritage of Newa art, you might have heard of Paubha or Thanka, two types of cloth painting known for their religious iconography. Many tourists leave Nepal with at least one of the two tucked away in their suitcases, hoping to hang a unique reminder of their travels on their walls. But for foreigners and Nepalis alike, few have heard of Bilampau, an elusive narrative art style that may have been inspired by Paubha. Bilampau in Newa means horizontal painting.

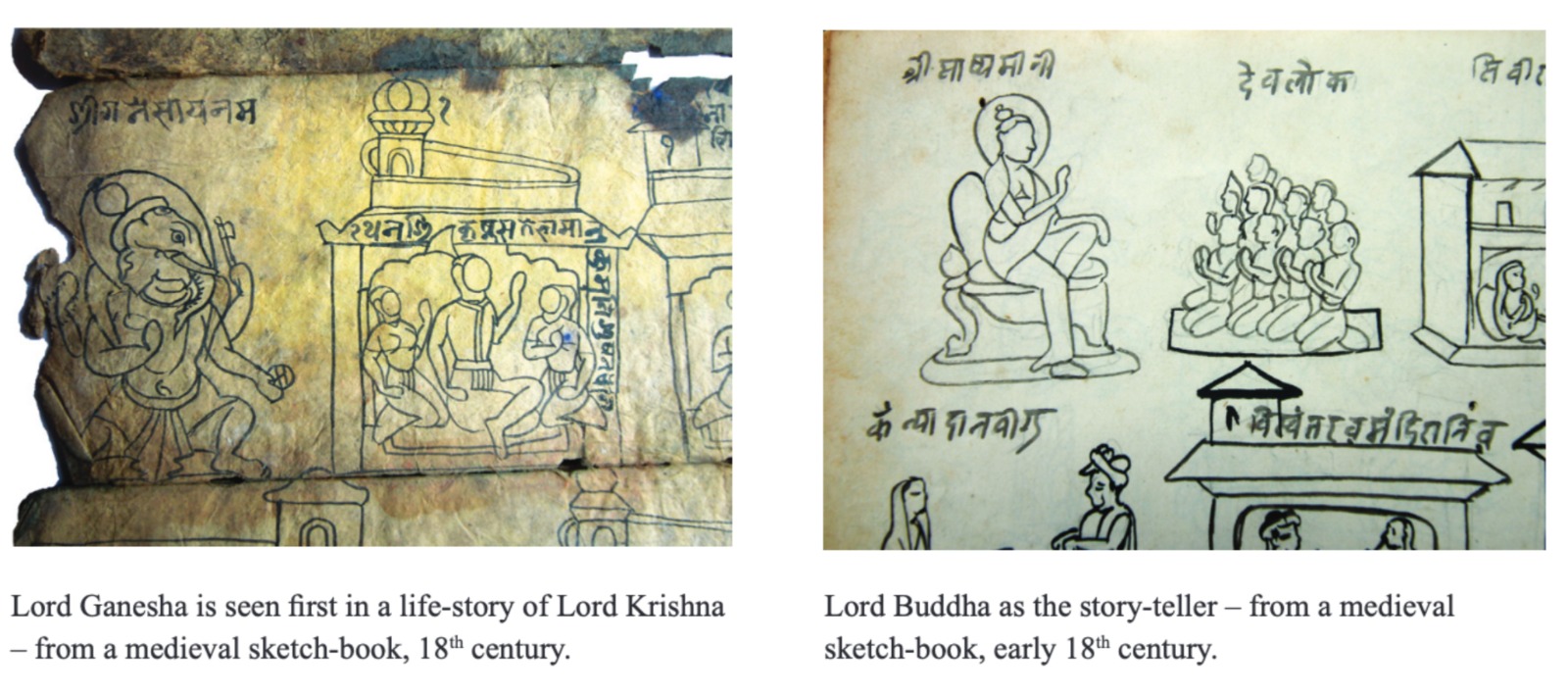

Though Paubha is a much more established and recognisable Newa art form, both Paubha and Bilampau are scroll paintings guided by Thyaa-saphu, folded sketchbooks that were kept by Newa families. Thyaa-saphu stipulates necessary thematic and narrative elements for Buddhist stories; Bilampau, for example, often begins with the figure of the narrator themselves, whether it be Lord Buddha—common in Buddhist scroll paintings—or Lord Ganesha, in the case of Hindu stories.

But Madan Chitrakar, renowned artist, researcher, and scholar, reveals that the similarities between Paubha and Bilampau largely end there. “The subject matter and motifs are very different,” he says.

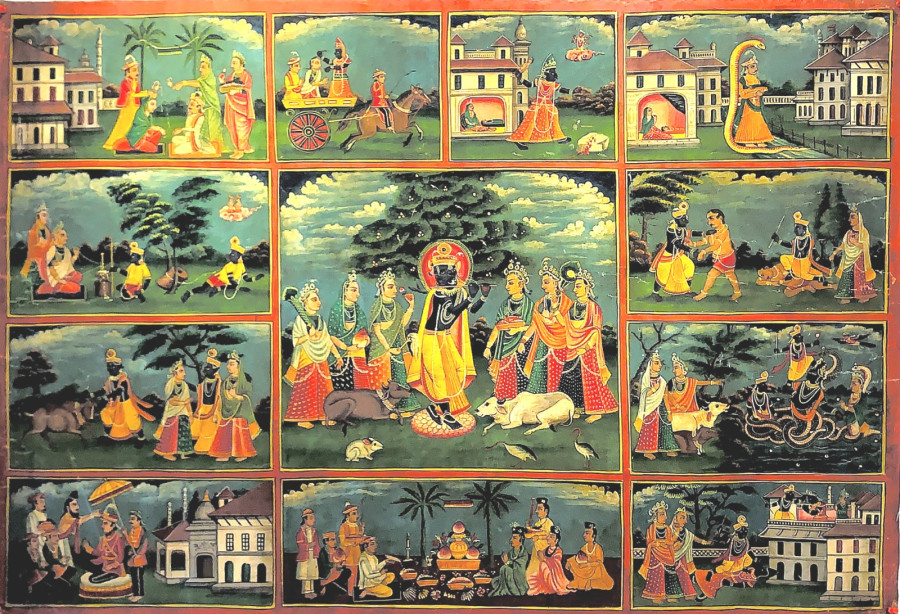

While Paubha’s religious characteristics support meditation and worship, the importance of storytelling is prominent in Bilampau and its “narrative scroll” composition. Unlike Paubha, Bilampau depicts stories with multiple elements and episodes.

This sequence is often established through a collection of frames on one scroll, though some Bilampau artworks utilise a single scroll without frame-by-frame separation.

Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha, museologist, curator for Nepal Art Council, and curator of the current Itumbaha museum exhibition, emphasises that Bilampau are not meant for veneration. “In ancient times, they didn’t have comic books, right?” she jokes. Instead, visual storytelling was done through creations like Bilampau.

On June 18, 2024, Siddhartha Art Gallery opened its doors to the public for its most recent exhibition on Kalighat paintings, Ganjifa playing cards, and Bilampau. Though the gallery certainly focused on the legacy of Kalighat, all three art forms underscore the unique cultural ties between Nepal and India.

At the opening, artist Chitrakar also spoke on the significance of Bilampau, calling it one of the most “misunderstood” forms in Nepali art history.

What does it mean to truly understand an art form? And when it comes to the expansive depths of art history, what does it mean to remember an art form in its entirety? How can we revive a dying art form back into the collective consciousness of the twenty-first century?

The earliest existence of the visual narrative technique in Nepal can be traced back to the 12th century, depicted not through scroll but through wood. Newa artists were also likely commissioned to create Bilampau for specific walls in Buddhist temples, hence its impressive horizontal length. Indeed, Bilampau also holds some surprising diversity in sizes and dimensions, with many ranging from nine feet to a whopping 78 feet in length—a testament to its visual significance.

Comparisons can also be drawn between Bilampau and Patachitra, a cloth painting form based in West Bengal, Odisha, and Rajasthan. Both Bilampau and Patachitra were created by Chitrakar artists in India and Nepal, and the two forms also share a reputation for story-telling. However, Bilampau is more commonly horizontal, while Patachitra is typically vertical in its episodic visualisation.

It is possible that Bilampau grew into its own art form from the influence of Patachitra, signifying another historical connection between India and Nepal, but so little is known about the evolution of Bilampau that it is difficult to come to a precise conclusion about its origins.

Today, most traditional Buddhist Bilampau are kept in local monasteries. According to Chitrakar, one of the most famous Bilampau is currently held in Itum Bahal. Kayastha notes that the Bilampau in Itum Bahal depicts the foundation of the Itum Bahal monastery.

During the Newa Gunla festival, which is celebrated according to the lunar calendar, the significance of Bilampau storytelling is also treasured amongst Vihara and Newa Buddhists. “For fifteen days,” Kayastha explains, “all the monasteries will display the objects they have in their storage, which people have donated over time. One of those objects would be the Bilampau.”

Kayastha highlights that the Bilampau is not only a source of education regarding the monastery’s history but also a source of community engagement. Members of the community take it upon themselves to safeguard their heritage and cultural objects, usually sleeping in the same room as the Bilampau and other artefacts.

At Siddhartha Art Gallery, there are two Bilampau, both depicting Hindu stories; due to the artistic shift towards Hinduism, the older Bilampau, consisting largely of Buddhist stories, is much less accessible.

Bilampau is no longer an active form in traditional Nepali art, which means that truly understanding its significance also begets recognising its disappearance from popular Nepali art discourse. Despite being one of the earliest forms of visual story-telling in Nepal, “it is almost forgotten,” remarks Chitrakar.

A quick Google search of ‘Bilampau’ results few substantial results except for a single scholarly article written by Chitrakar himself.

The fear of this art form growing obsolete extends far beyond art history, just as art history itself holds broader implications on the importance of culture and identity.

In Nepal, Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal declared that the country’s citizens share a common responsibility to protect traditional Indigenous culture, calling it the “identity and prestige” of Nepal as a whole.

Traditional festivals and art forms are certainly still celebrated and recognised, whether it be on the streets of Kathmandu or within one of the city’s museums or galleries, but several artisans and scholars have shared their growing concerns about the future of traditional Nepali art.

Many artists from the older generation, for example, fear that the younger generation will no longer continue the artistic practices—such as Paubha painting—that their families have inherited for generations.

We must take it upon ourselves to raise awareness and actively engage with the artists and cultural significance that accompanies these forms—otherwise, our collective apathy might result in these traditions reaching the same untimely fate as Bilampau.

Though Bilampau died out a century ago, one method of reviving its presence might entail a call for collectors to bring their Bilampau pieces forward, increasing public accessibility. For others, simply talking about Bilampau and remembering its place in history might be more than enough.

“When we talk about Nepali art traditions,” says Chitrakar, “we must not miss Bilampau,” echoing the value in appreciating a lesser-known art form. And when we remember Bilampau, we must also hold on to the other art forms that are still surviving, carrying legacies that have spanned across entire wars, nations, and generations—and, if all goes well, with many more journeys to come.

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu