Books

Exploration of diverse worlds through unreliable eyes

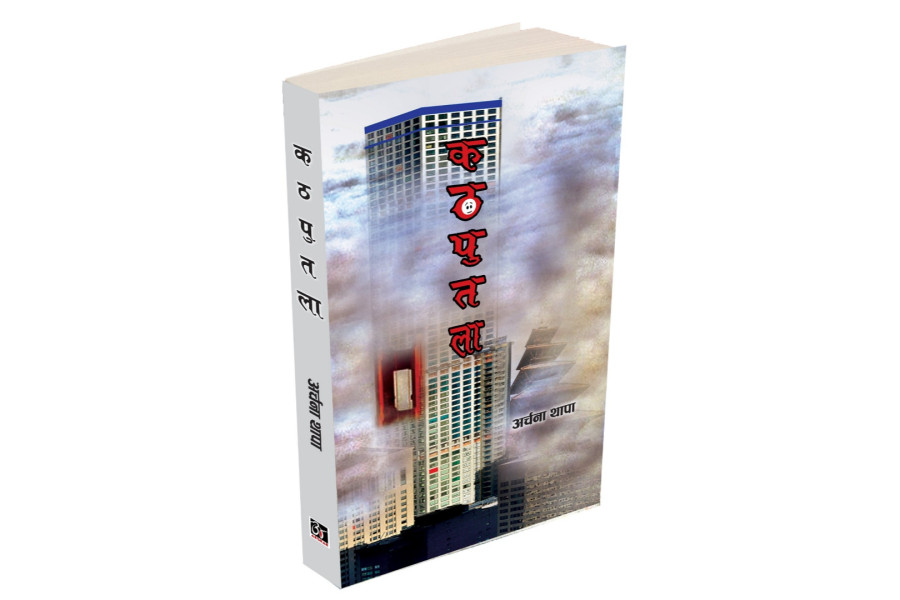

The remarkable examination of social problems in diverse settings makes ‘Kathputala’ a must read.

Kshitiz Pratap Shah

Archana Thapa’s collection of stories, ‘Kathputala’ first came into my radar in 2020. The first thing I remembered about the book was its expansive nature and how this collection had stories from multiple genres. Across eight fairly long stories (most of them are around 30 pages), Thapa covers a range of settings and issues, from the inner workings of a post-apocalyptic, robot-run society, to a reimagining of the Ramayana itself. While the experimentative elements definitely stand out, my recent re-read also reminded me of the heart and grit these stories possess.

From marvelling at just how new these mind-bending concepts were for Nepali literature (the book was published in 2017), I have now come to understand the subtler elements of the text. With both reads, ‘Kathputala’ never ceases to fascinate me with its radical yet relatable storytelling.

Expansive and introspective

The stories in ‘Kathputala’ cover a wide range of settings. The titular story, ‘Kathputala’, is based in an imaginary futuristic world where people rely on governmentally imposed robots to do every activity, including eating, leaving home and even procrastinating. I found definite connections with many global literary texts, even at a cursory glance. The comparison between the personal robot here and the ‘Big Brother’ surveillance mechanism from ‘1984’ is pretty evident. Using a Western classic as a direct inspiration reaffirms that Nepali literature is willing to produce works that transcend realism and explore new avenues.

Thapa’s short stories also draw extensively from real issues and Nepali literature. Alternate narratives based on Hindu mythology are common in Nepal, case in point Binod Prasad Dhital’s classic ‘Yojana Gandha’ or Krishna Dharawasi’s ‘Radha.’ With her story ‘Vivastra Ramayan,’ Thapa goes one step further and explores Minakshi, Sita and Lakshman in a modern Nepali setting, and raises the important question of the biased voices of the storytellers in our myths and legends.

The stories are also based on issues within Nepali society. The climax of ‘Parakampan’ is induced by the 2015 earthquake, while ‘Vivastra Ramayan’ is based around the Madhesh Andolan, both fairly recent crises. Similarly, these stories also poignantly question problems faced by people and are grounded in regard to the voices they represent.

‘Parakampan’ focuses on the subtle yet debilitative hold of the male mindset of controlling and doubting women, induced by a lifetime of familial bullying and gendered socialisation. ‘Antardaha’ and ‘Paramatma Samaahita’ showcase the issue of labour migration, the former through the fracturing of old families and the latter through the temporary nature of newly formed ones.

Introducing unconventional voices

Despite being rooted in Nepali literature, Thapa’s stories insist on questioning traditional ideas and introducing new ones. The innovativeness is evident not just in the setting but also in the characters’ motivations.

A classic example is the story ‘Parakampan,’ which is my favourite in the collection. The story follows a couple, Parakram and Mohini. Parakram is from a rich, aristocratic military family. Marrying someone from a non-military, non-Khas Arya caste is seen as an offence by Parakram’s family. Yet, the wife Mohini, constantly insulted by her in-laws for her parentage, is shown to pay little attention to the mistreatment and tries her best to maintain appearances.

While it would be natural to see the couple as valiant trend-breakers, Thapa chooses a different narrative. Parakram, a seemingly supportive husband, is shown to be full of doubts and willing to turn on his wife. Instead of presenting a hopeful narrative, Thapa questions the idea of romantic love itself and warns us of the social mindsets that are difficult to revert. ‘Parakampan’ showcases an example of the unreliable narrator, a tool Thapa often uses in her stories.

In the story ‘Kathputala’, the seemingly happy Malak gradually turns impatient, indecisive and violent. In ‘Antardaha’, Labhu denies his harassment until he has to face the matter directly. This is not to say that these characters are antagonistic in lying to themselves about their traumas. With the stories, Thapa emphasises flawed characters who have gone through a lot but attempt to live with a sanitised version of reality.

Finally, a note on the length of the story; they can be fairly long, and very reliant on past memories introduced too late into the story. I felt that there were sections within the stories which did not add much to the main plot. Yet, to counter that, the stories have immense repeated reading value. Knowing the ending beforehand propelled me to look for the hints scattered by Thapa throughout.

The remarkable exploration of social problems in diverse settings, and a thought-out dissection of character psyches—especially the idea of toxic masculinity—make Archana Thapa’s ‘Kathputala’ story collection a must read.

Kathputala

Author: Archana Thapa

Year: 2017

Publisher: Akshyar Creations Nepal

22.64°C Kathmandu

22.64°C Kathmandu