Books

An exploration of personal faith

Part travelogue, part memoir, ‘Tripping Down The Ganga’ reveals many river aspects central to the Indian mind.

Madhulika Liddle

In the heart of Rome’s Piazza Navona stands one of the city’s most famous fountains: Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, the ‘Fountain of the Four Rivers’. Designed in 1651 by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for the then-Pope, Innocent X, the fountain depicts the major rivers of the four continents where papal authority had spread: the Nile, Danube, Rio de la Plata – and the Ganges

.

For the average Western tourist, it’s an impressive sight, a grand spectacle. For the average Indian, too, it is that, and perhaps too an evocation of pride: this is our river, our Ganga. (It’s a different matter that Bernini’s Ganga is a muscular and heavily bearded man, not at all the makara-riding goddess Indians know her as).

But, inaccuracies and all, Bernini’s Ganga is an interesting reflection of just how vital this river is, how resoundingly a symbol of India. In Europe, which in 1651 still knew little of the exotic East, the Orient was exemplified by the Ganga; in India, it has been not just water, not just life, but much more. Mother, saviour, purifier, the very heartbeat of India, the core of Hinduism.

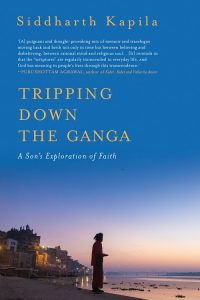

It is this river that Siddharth Kapila sets out to trace in Tripping Down the Ganga: A Son’s Exploration of Faith (Speaking Tiger Books, 2024). The book brings together Kapila’s travels along the Ganga: more specifically, to seven spaces situated beside the river that are the focus of yaatras or pilgrimages for Hindus. As Kapila explains in his introduction to his memoir, these journeys took place in two different time periods: one, in the 7 years between 2015 and 2022; and another in earlier years, when Kapila went on yaatras along with his mother.

These journeys intertwine through the book, the same spot – whether Kedarnath or Badrinath, Gangotri or Kashi – experienced at two different times. Kapila intersperses memories of less than a decade back with those of nearly 30 years ago, creating an interesting palimpsest of places, pilgrimages, people.

The people are what shine through bright and clear here, because it is their faith that takes centre stage. Kapila’s conversations, both with those around him and with himself, grow increasingly insightful and deep as the book progresses.

He talks to holy men who brave ice-water baths in Gangotri; to Naga sadhus, the warriors sworn to protect the faith; to the formidable (and unsettlingly ‘different’, for some people?) Aghoris, who haunt the cremation grounds at Kashi. He discusses spirituality both with Westerners journeying through India, as well as his partner, a young Aghan edging towards Buddhism.

And, importantly, he dwells on the faith of his mother, a tax lawyer who is deeply devout and for whom her religion comes through as the fulcrum of her life. Many of the yaatras Kapila narrates are performed in his mother’s company, but there are other ways too in which she enters the narrative: in conversations, in her son’s views on organised religion and faith (often widely divergent from those of his mother’s), even in his discussion of the dichotomy that seemingly reveals itself in his mother. A hard-headed, clear-minded, utterly rational lawyer when she’s at work, but a believing, ritual-driven devotee when she’s not.

The faith, in its many avatars, its many forms, shows up in diverse ways. For instance, the quiet devotion of the many people who give up their lives with family and home to turn sanyasi (and there are several of these in this book, including the Kapila family’s own Swamiji).

But, in contrast to that quiet devotion, the boisterous and loud ‘masti married to bhakti’ which Kapila describes in context of the kaanwariyas who trek every season to the Ganga to draw water. Or, as he puts it, the ‘Great Indian Free-For-All’: pushing, shoving, loud, exuberant devotees, making no bones about their religious fervour.

Tripping Down the Ganga, however, isn’t merely an exposition of the author’s own faith or the faith of those he encounters on his journeys; it is, too, a closer look at the religion, and at its intersection with other religions, other organised structures; at Hinduism’s fraught relationship with Buddhism and its even more fraught relationship with Islam; at the burgeoning (especially in recent times) of the connection between religion and politics, and the hidden realities of issues such as the Gyanvapi Masjid and the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor Project.

Part travelogue, part memoir, part introspection, this book manages to bring together many aspects of the Ganga and all that surrounds its status as India’s most sacred river. Kapila’s writing is conversational, occasionally even humorous.

He makes no pretence to erudition (though his research is obviously solid and extensive), and there’s a sincerity, a clear-sightedness that shines through. It does not, however, dull his faith, and one gets the impression that this is an individual whose faith is unswerving, but not at the cost of his humanity: he straddles two worlds, just as his mother seems to do. That subtitle ‘A Son’s Exploration of Faith’, turns out to be a worthy tribute to Kapila’s mother.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu