Columns

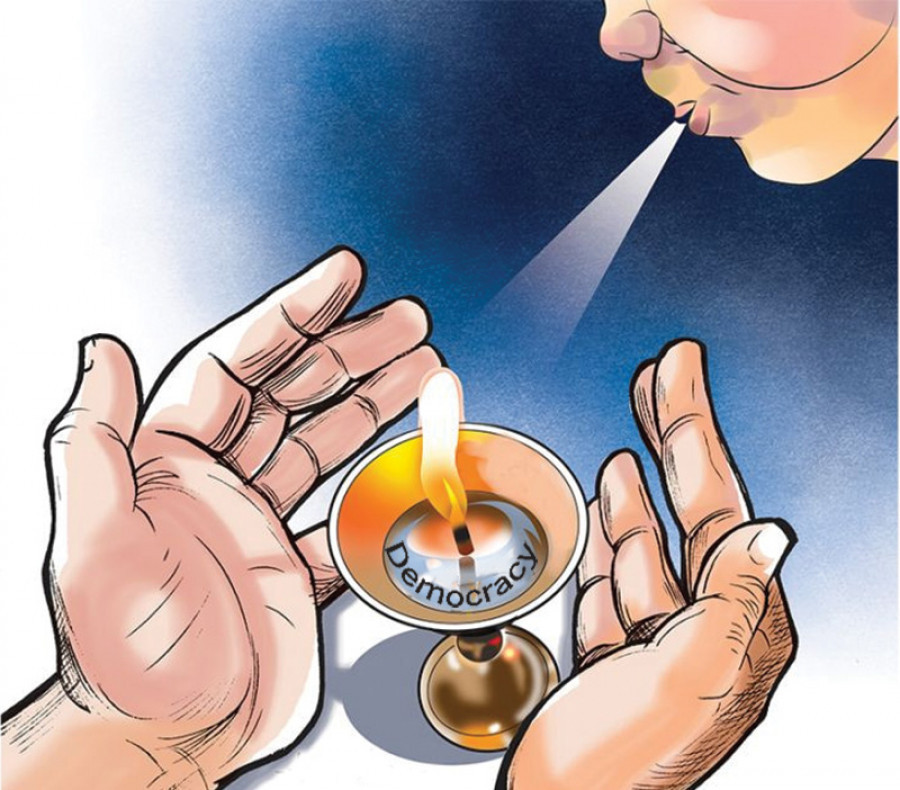

A season of revolutions

Neither elections nor revolution is a solution to the current problems.

Ajaya Bhadra Khanal

Spring, a season of unrest, is here. Those yearning for democracy and good governance are wishfully talking about a final revolution. People are tired of needing to fight new revolutions every ten years or so, something that has become a habit for Nepalis since 1940.

There are significant differences in opinion over the current state of affairs. While a large number of people, including a significant chunk of the civil society, argue that the only way is to control Prime Minister KP Oli’s excesses, others believe that popular elections will put Nepal's democracy back on track. Given Nepal's situation, neither elections nor popular revolution will be enough to solve the current problem, which is more deep-rooted and can only be resolved if our political parties and our democratic institutions perform as expected by our system.

One of the reasons why Nepal's democracy is under strain is because of the personality of our current prime minister. He is becoming more and more unhinged, disrupting our institutions and violating the rule of law. It is a good sign that he is affected by what others are saying about him and what others think about him. But it will only last as long as he allows them to speak.

There are already signs that he might misuse tools of the state if he feels that he is losing the propaganda war. Another sign that he is unhinged is his veiled threats to the judiciary and attempts to display the might of the state, particularly the Nepal Army. Oli wants to project that the Army and the Supreme Court are behind him. This is sure to drag down the image of both the judiciary and the military.

Oli's attempts to court the Communist Party of Nepal led by Netra Bikram Chand is also problematic. The Maoist party's core principle is the need for an integrated war and the party's whole ideology and organisation is built around this core principle. Unless the group renounces this ideology, we can safely say that everything else is a temporary tactic to gain an advantage. They can get respite from the pressure of security agencies, secure the release of prisoners, and spite Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

The deeper issues are linked to power inequality, the relationship between the people and the state, and a growing influence of the thieves of the state. The barricades surrounding Tundikhel and the shrinking of public spaces like Kamalpokhari have become emblematic of our system. The first symbolises the powerlessness of the citizens against a feudal state.

While it takes little or no effort to maintain the barricade by the elites who have captured the state, the weak need more than they have to dismantle the status quo. Kamalpokhari symbolises the collusive relationship between the state and thieves. More than 40 years ago, the official size of Kamalpokhari was about 52 ropanis. Now it is said to be 22 ropanis. Unscrupulous realtors, in partnership with the state, have stolen about 60 percent of the public space.

Of revolutions and elections

A new revolution is also not the answer. Revolutions have failed time and again to address the question of democratic accountability, to ensure that the people enjoy the fruits of democracy. They are even a cruder form of popular mandate.

Revolutions can only dismantle existing systems, they cannot stamp their mark on the new systems that emerge. As a result, the fruits of democracy are stolen by thieves in collusion with the state before they can be enjoyed by the country or the people.

Although a series of protests by citizens culminated in a citizen's charter, the movement has failed to draw the support of enough citizens or even put pressure on the executive. There are several major factors as to why the citizens and the civil society are finding it more and more difficult to unite for the cause of democracy and the rule of law or to exact accountability.

For every fact or information, there is another set of alternative truths and misinformation. Then the citizens, especially the so-called civil society members based in urban areas, find it really difficult to trust each other. The inability to trust is not an inherent weakness. In fact, it is a response borne out of the repeated experience of betrayal.

Another reason is the presence of a multiplicity of issues that are inherently divisive. For example, a lot of people agree on the need for good governance, rooting out corruption, and rule of law. But these issues are frequently displaced by more salient issues like identity, caste, ideology, and nationalism.

Elections will not solve the problem either. They can deliver retributive justice. After every election, we look back and wonder at the collective wisdom of the electorate, which appears to have an uncanny ability to punish the excesses of politicians and political parties.

But can we count on the electorate to continue to instil a sense of accountability? Unfortunately, the answer is no. We require checks and balances in our democratic system to ensure that we are not under the rule of politicians driven by bloated egos.

Accountability and delivery

Revolutions and elections are only one part of the coin. The other part is a system designed to deliver the fruits of democracy. Those who can actually solve the problem are political parties.

Nepal's democracy is unthinkable without the political parties acting as a bridge between the state and the people. Unless the parties are designed around democracy and transparency, modern democracies will not work.

Already, the features of Nepali society have been transformed from the past. While feudalism has waned, it has been replaced by another more rigid system buttressed by modernisation, capitalism and rigid institutions. These factors will make it more difficult for people to engage in democracy in the future, and make it easier for a network of unscrupulous politicians, state institutions and private sector actors to control the state and the quality of its democracy.

Unfortunately, some of the important parties have failed. The distance between civil society and Nepali Congress is growing. If there are elections in the near future, Nepali Congress will receive less support from civil society.

Systemic accountability must come first before popular accountability. Elections in Nepal have never solved the problem of good governance or economic development. These problems must be solved by our democratic institutions. And right now, we have a significant test of the ability of our democratic institutions to exact accountability from political leaders and institutions that have no sense of accountability.

Two examples highlight the failure of Parliament. The first is its inability to control the excesses of KP Oli or his move to dissolve the parliament. It is the reason why, in the last three years, the executive has been able to misuse democratic processes to take over democracy. The second example is Parliament's failure to shape policies, because it has succumbed to the habit of delegated legislation. It means that legislation enacted by Parliament is only skeletal in nature, the executive fills in the flesh and does what it wants with little scrutiny.

The judiciary has given a verdict to protect Nepal's constitutional democracy, to ensure that systems of accountability exist beyond the popular vote. We need to see how everything else unfolds.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu.jpg)