Columns

Electoral syndicate against women

From the first election, one thing that hasn't changed is the politics of hegemonic masculinity.

Chandra Bhadra & Sucheta Pyakuryal

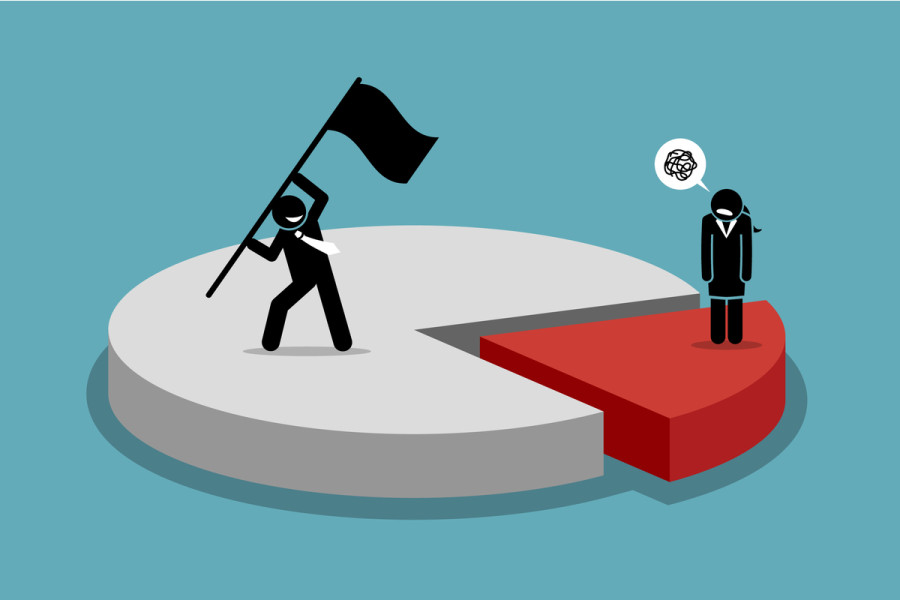

On the eve of the 2022 local election, staying mute as mere bystanders when women’s representation in local bodies is being strategically slashed is no more an option. If one were to trace the evolution of elections in Nepal, one thing that appears to be unchanging and static over the years, formidable and overbearing, especially to women voters and candidates alike, is the politics of hegemonic masculinity. Elections reveal how hegemonic masculinity overbears state power as well as the governmental, non-governmental and private mechanisms by which it subjugates or excludes women. Even though the constitution guarantees fair political representation, women, especially those from the socio-political periphery, continue to be a political minority although they are the actual majority. This says a lot about how our supposedly democratic polity that formalistically upholds the mission of prioritising fair political representation and equitable power and resource distribution is in the clutches of hegemonic masculinity.

Of course, the Nepali feminist movement has made considerable strides since the early 1990s. Many women-centric amendments were carried out because of this movement and its dynamism. What it has not been able to do, however, is thwart the hegemonic masculinity that exists in the polity as patterns and practices that justifies hierarchical and unequal power distribution between men and women. This hegemony is culturally exalted and politically legitimised despite constitutional reins.

Old boys’ candidacy

A separate culture of election has emerged where femininity is denied political space, scope, and subsequently, legitimate candidacy. The allocation of candidacy within the parties—where the old boys’ candidacy go uncontested and women are given losing constituencies, where winning constituencies are snatched from women and given to the blue-eyed boys of the parties, where arguments of “unavailability of women of substance” circulate that substantiate the culture of misogyny within the parties, and where coalitions are forged to make sure partymen come on board—rebuffs the very democratic ideologies that the parties stand on.

It is a common knowledge that without viable representation, democracy becomes obsolete. Our constitution ensures fair representation and the constitutional provision for women’s representation compels men-led political parties to field women candidates. That, they do grudgingly, portraying themselves as magnanimous partymen and patriarchs who are giving opportunity to the political subalterns or the underdogs. This political underdog syndrome became stark in the 2017 election when deciding the mayoral and deputy mayoral candidates of urban municipalities as well as the chief and deputy chief positions of rural municipalities all the way down to the ward level.

Overall, 2017 was an optimistic year for women as political parties fielded at least one female candidate for either the head or the deputy head at the local level as mandated by the Local Level Election Act 2017. After Nepal adopted a federal model, it seemed that the issue of representation was being prioritised by our republic. However, five years later, optimism among women completely evaporated as their representation backslid. In the last election, females accounted for 41 percent of the elected representatives. During this election, the number of women’s nominations has receded to 37.8 percent.

Even in 2017, the gap between male and female representation was glaring. Of the 5,837 contestants for the post of mayor or chair, only 368 were women. In total, of the 10,201 candidates contesting, 3,961 were women and 6,239 were men. To put it further in perspective, 6 percent of the mayoral candidates were women as opposed to 94 percent for men. However, general optimism prevailed; although a majority made it to the subsidiary position of deputy chair, they made it, nonetheless.

During the Constituent Assembly days, party women had come up with the idea of forming an inter-party women’s caucus, and were actively forging a feminist alliance among themselves. Later, the caucus dissipated because the female members were “admonished” by the patriarchs from their respective parties. Women are restricted in politics, and this violates their constitutional right. Article 38 (4) states, “Women shall have the right to participate in all bodies of the state on the basis of the principle of proportional inclusion.” However, structurally and systematically, women are being denied their constitutional rights.

The actions of the patriarchal electoral syndicate get solidified via the apathy of male leaders of all political parties and the patriarchal bureaucratic structure of the Election Commission. Once again, the mayors and chiefs will be overwhelmingly men. Not only that, the election coalition has also given parties free rein to field only men as candidates which will substantially diminish women’s political participation in the 2022 election.

The patriarchal electoral syndicate strategically planned and negotiated the selection of candidate using nepotism in the hegemonic masculine inter-party alliance. Despite this, several women have demonstrated sheer political will and determination, and are filing for candidacy for the top level positions. Among them, if some happen to be related to political patriarchs, their candidacy is ridiculed, and they are slapped with the tag of being “objects of nepotism” unlike the male kin of the political patriarchs who are, in fact, encouraged to get into politics.

Mere extension

These women are reduced to a mere extension of the party patriarchs they are related to, not knowing their political history before they became related to these political men. From Mangala Devi Singh and Sahana Pradhan all the way to Shrijana Singh, women have had to defend their candidacy unlike the male relatives of political leaders. How do women ward off this perpetual hegemonic masculinity? Men and women political and academic analysts, journalists, voters and even women’s political subunits use the hegemonic masculine lens to pass judgment on women who are politically connected. Even highly acclaimed democracy experts seem to excuse the #MeToo tainted urban political strongman than accept the candidacy of “politically connected” women.

It is high time feminist researchers actively engaged in pushing through this pervasive hegemonic masculinity by documenting and showcasing women candidates as formidable political candidates. Additionally, the Inter-Generational Feminist Forum needs to visit all urban and rural municipalities to encourage women candidates to get trained and motivated to take up as many mayoral and municipal chair positions as possible. The only female chief of Pokhara Metropolis ward 1 keeps organising gender equality and women’s empowerment activities in her ward where “gender sensitisation to end violence against women via men’s alliances” gets regularly initiated under her leadership. Best practices are all around us, we just need to recognise and routinise them if we want Nepal to harness socio-political and economic development for all.

16.16°C Kathmandu

16.16°C Kathmandu