Columns

Jureli chari sings the blues

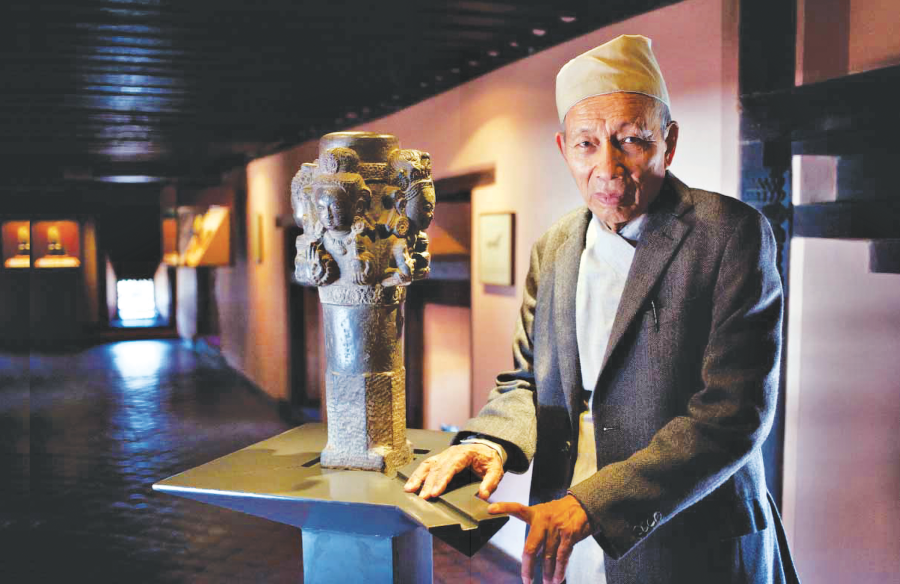

When it came to chronicling Nepal’s enormously rich folk cultures, historian and culture expert Satya Mohan Joshi was without parallel.

Dinesh Kafle

In 1944, as he lay on the deathbed in a rural village away from home, Satya Mohan Joshi wondered if he would ever see his wife, his infant daughter and his parents again. The then 24-year old Joshi, a raithane of Lalitpur, had been commissioned to conduct a socio-economic survey of Tanahun district. He had contracted malaria when he was in Rishing-Ghiring and was left with nothing but an endless wait for death. A junior colleague who accompanied him and was infected by the same disease had been left for dead on the banks of a rivulet next to the village, and as he battled high fever, Joshi was certain he was next.

But that was not to be—not for the next eight decades at least. As Joshi says in his memoir, written excellently by Girish Giri, he had yet to learn the song of the jureli chari, the nightingale, in Nepali folk tales. He had yet to learn the impermanence of mortal life and the permanence of regeneration. He had yet to learn that he had emerged from shunya—nothingness—and would return to nothingness, but only after fulfilling his function on this earth as a thinking being.

Help arrived in the most unexpected of ways in that far-away place, and Joshi was ferried to Pokhara to be treated. He recovered, as did his colleague. Having come face-to-face with death in his first job and first foray outside the valley, Joshi could very easily have returned to his cocoon in the Newari neighbourhood of Patan. But then, as destiny would have it, the mountains called him again, and it was there that he soon found his calling—as a diligent chronicler of Nepali folk stories, songs and myths.

A chronicler of folklore

Many of his plays, poems and stories were rooted in the Newari cultural tradition. But rootedness itself was a fluid concept for Joshi, as he found his footing in every geographical terrain or culture into which he ventured. Wherever he went, he immersed himself deep in the raithane tradition and came out with myths, stories, folktales and songs that had recorded the lives of the people of those places for countless generations. And in doing so, he became one of a handful of Nepali cultural luminaries who have enriched Nepali folk art, literature, and culture.

Such was his eagerness to immerse in a new culture that he once sat through the night to listen to a live dohori in a rodighar in his early travel to western Nepal. By morning, he had learnt enough to replace the male lead and sing opposite the female lead, the most famous singer of the region at the time, no less. Over the decades, as he climbed the ranks of his professional life, he would travel the length and breadth of the country and play an unparalleled role in Nepali cultural history in holding a mirror to the country to show its enormously rich folk tradition. Even as he did so, Joshi had no qualms about stating that the songs he had collected were not his, but he had just been a collector, not creator, of those songs. "I had strung those songs together in a book form, just as we string flowers together to make a garland; the flowers belonged to the villagers. So the songs were the wealth of the villagers." The humility of acknowledging his limits would be his life's mantra, which he had learnt from the jureli chari, the nightingale, his lifelong friend and teacher.

In a long and healthy mortal life worthy of jealousy, and a prolific creative life worthy of emulation, Joshi wrote dozens of books of essays, research papers, plays, poems and stories. In his writings, Joshi did not just bring to light the myths of a place or culture but also the historical events that have found a place in the oral tradition. When he visited China, he found a whole manuscript worth of material on Nepali artist Araniko waiting for him to be rediscovered. The subjects and objects of his study ranged from artists to sculptures, Nepali coins to national census, and mythological heroes to chaityas. He went on a survey of the folk culture of Karnali and came back with a book manuscript called Itihas, the first in a five-part collaborative book series on Karnali. But compelled as he was by his creative element, he would hardly be content with just a straightforward chronicle of Karnali's folk culture. So he came up with another creative piece, a play titled Sunkeshari, based on a folk story about a girl named Sunkeshari Maiya.

Joshi was also acutely aware of his position as a creative artist, as he infused political elements in what at first glance seemed cultural plays, including Bagh Bhairav and Sunkeshari. His creative canvas was multi-layered, replete with cultural and geographical nuances, yet inspiring serious readers and audiences to seek deeper political motives interspersed in his craft.

Almost always clad in daura suruwal, coat and plain topi, his tall, lean figure would be an unmistakable presence in most major literary-cultural events in Kathmandu Valley in the past few decades. One could have wondered why the organisers were bothering an old man in his eighties, nineties or hundreds to attend such events. But then those who knew his enthusiasm to meet the younger generation of writers, artistes and musicians would know that it was these events that kept him alive and kicking. Joshi saw in the creative exchange between the old and the young the possibility of continuity and regeneration, as if it were a palimpsest, exemplified best by the eternal singing of his favourite bird, jureli. It was the unhinged energy of young creative minds, whom he adoringly called friends, that kept him relevant in a fast-changing world.

Song of the nightingale

Seventy-eight years after awaiting death in the distant hills in western Nepal, Satya Mohan Joshi, at 103, finally said he had had enough as another vector-borne disease—dengue—infected him again. As his hometown becomes the epicentre of the disease and as hospitals across the country fill up with patients, it seems as if nothing has changed in these intervening decades as the death of dozens and infection of thousands of citizens becomes a casual occurrence and not an aberration.

Among those who came to pay their last respects to the centenarian were those who have done precious little to tame the epidemic. In his afterlife, Joshi might have laughed off the stupidity of such imbeciles and forgiven them, for he had made it his life's goal to live with chintan and not chinta, drawing from his jureli philosophy. He elaborates his chintan in his memoir thus:

"In this earth, every child born to a mother must return to the shunya, from where it had emerged. But the jureli never dies, does it? For, the jureli born today sings exactly the same song that its forebear born a million years ago had sung. How, then, can we consider the jureli dead? It is just that the jureli's mortal body has ceased to exist."

In his mortal avatar, Joshi outlived his peers and was already an old man when most of us alive today saw him for the first time. In his intellectual life, he outdid his peers as a chronicler of Nepali life. As a living, creative being, he produced a body of work that would become an essential subject material for students of art, literature and culture. And when he died, he left his mortal body to be an object of study for students of medicine. In becoming a subject and object of scrutiny—both literary and anatomical—he has reinforced his philosophy of the perpetuity of life; he has become a jureli himself.

Perhaps the jureli sang the blues this morning. But as Joshi's favourite line in PB Shelly's poem 'To a skylark' says, "Sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought." The jureli will start chirping the songs of regeneration soon again, as the succession of life after death is the only Satya there is.

22.65°C Kathmandu

22.65°C Kathmandu