Columns

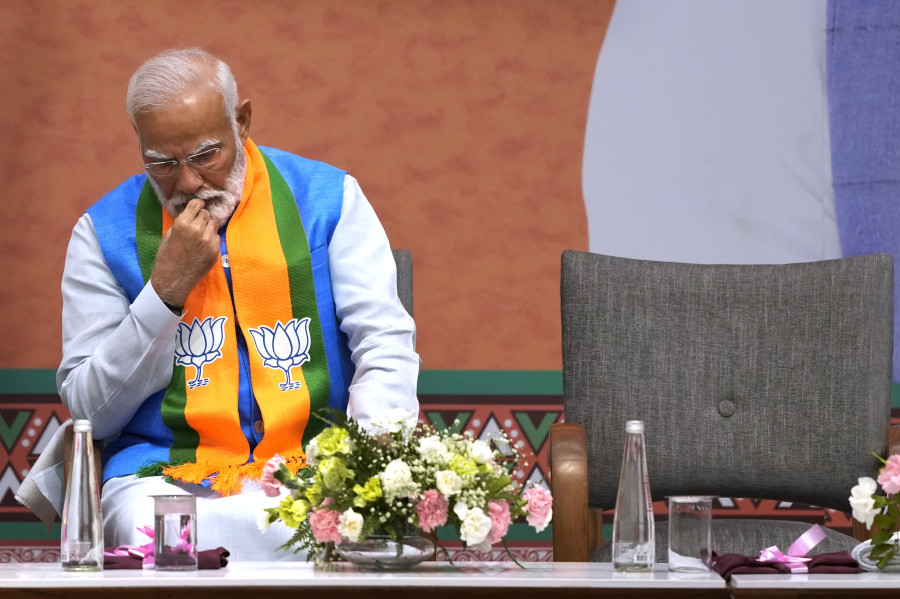

A setback for politics of hate

Having weakened the democratic foundations of the country for 10 years, Modi is set to remain in power.

Dinesh Kafle

One great irony of the 2024 Indian parliamentary elections is that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost the Faizabad constituency in Uttar Pradesh, where, in the city of Ayodhya, Prime Minister Narendra Modi earlier this year organised a hasty consecration ceremony for the Ram Lalla temple erected on the ruins of the 16th-century Babri Masjid. The people of Lord Ram’s mythical janmabhoomi seemed to have had enough of the politics of hate, whose seeds had been sown by Lal Krishna Advani in 1992 with the Masjid demolition and which had been expanded across the country by Modi throughout his career.

In the Banswara constituency in Rajasthan, where Modi, during an electoral speech, warned the women that the Congress would confiscate their mangalsutras and give them to the “infiltrators” [read Muslims], the BJP candidate faced a drubbing. The world’s largest democratic elections have thrown in a legion of interesting anecdotes, surprises and shocks that the media will bring to light in the coming weeks, but the most important story today is that the politics of hate that had become a mainstay of Indian politics in the past decade under Modi has faced a setback. At least for now.

Divider-in-chief

With two untrustworthy coalition partners, Nitish Kumar and Chandrababu Naidu, pledging their allegiance to the National Democratic Alliance, Modi is set to return to power for a third time since he stormed into New Delhi’s power corridors in 2014. Technically, this is a feat only Jawaharlal Nehru before him had achieved in independent India. But make no mistake—Modi is no Nehru, and any attempt at equating the two is blasphemy in the realm of democracy. Nehru’s electoral campaigns—in 1951-52, 1957 and 1962—focused on communal harmony, development and nation-building. Having emerged from the clutches of British colonialism, a bloody partition and a defeat with China, India under Nehru was a nation awaking to life and freedom, a long-suppressed soul finding its utterance as Panditji prophesied in his midnight-hour speech.

Conversely, Modi has upended the founding ideas of a secular, democratic India, oiling as he did the gigantic social-bureaucratic machinery with communal hatred. As the desperation for fresh air even among his most trusted voters in the Hindi heartland became apparent, Modi doubled up on bigotry even as he rained insults on his opponents, demonised the marginalised community, and hypnotised millions of Indians into looking for an enemy among their compatriots. Once he started believing his own fantasy of creating an opposition-free India, he did all that could be done in a political culture bereft of morality—throwing opposition politicians behind bars, scuttling free speech, suppressing the media, and manipulating a section of Indians into believing that “Hindu khatre mein hain”.

Another Gujarat model

It is interesting [read scary] how Modi continued to change his enemies over the years to bring India where it is today. In 2014, his enemy was poverty, as he fought elections with a commitment to bringing “achchhe din”, a so-called replica of his Gujarat model of development. In 2019, his enemy was Pakistan, as he projected his image, in the wake of the Pulwama terrorist attacks, as a valiant fighter who would enter the enemy’s house and kill them. Come 2024, his enemy turned out to be his own people—the Muslims. Not that the Muslims were spared in Modi’s previous terms—he continued to maintain deafening silence even as Muslims, and in some cases, Dalits, were lynched by far-right Hindutva mobs in broad daylight.

As Modi focused his attention on transforming his image from “vikas purush” to “Hindu hriday samrat” and finally a demigod—he confessed, to the embarrassment of his devout bhakts, that he was born of divine power and not his biological mother—he failed to realise that the demons of communalism, once unleashed, resist a return even to the master. It was as if a metaphorical Gujarat model he hates to be reminded of was manifesting itself. No matter how hard he tries, he has failed to erase from public memory the pictures of the city that burned for three days, with Hindus and Muslims killing each other, even as he kept saying “Mera Gujarat jal raha hai”, as his character, played by Vivek Oberoi, shows in his hagiographical film, PM Narendra Modi.

After the humbug, the humbling

So triggering was the very presence of Modi at the helm that liberal Indians are celebrating Modi’s failure to garner a majority for the BJP this time although he is set to come back. That was the level of expectation among the people of the world’s largest democracy. Surely, the electorate was tired of the Hindu-Muslim rhetoric the Right-wing politicians and media anchors repeated day and night. Equally, the zeal of the opposition to keep fighting despite being hit below the belt persistently helped the people see the option they had been overlooking. Especially, the fight-back of the opposition is also the story of the coming-of-age of Rahul Gandhi. The so-called “Pappu” is back with a bang.

But the Modi era is far from over yet. Despite the change in the numbers, Modi will remain at the centre of Indian politics, albeit with a loss of sleep over a possible paltibaaji by his partners. But what is certain is that he will have to bring vikas back to his political rhetoric now. For there is a risk of his turncoat partners presenting an answer to the rhetorical question: “Modi nahi toh kaun?” Now that he has realised that a Congress-mukt Bharat is impossible, Modi would do well to work for a kalesh-mukt Bharat. That way, he wouldn’t have to go to some Himalayan cave for meditation for spiritual cleansing immediately after a vitriolic electoral campaign.

22.64°C Kathmandu

22.64°C Kathmandu