Columns

The subtext of the text

As India expands regional outreach, Nepal must pursue foreign policy in its own larger interest.

Sanjeev Satgainya

Less than a month after the new coalition took shape in Nepal, Delhi sent its emissary to Kathmandu. It was Vikram Misri’s second foreign trip within a month since his appointment as India’s foreign secretary, after Bhutan.

Getting too much invested into whether the alliance of the two largest forces, the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML, in Kathmandu, was/is of India’s liking and whether Delhi was caught by surprise at UML boss KP Oli’s return to power, will be a sheer waste of time.

It, however, is a fact that the Narendra Modi government did feel the need to renew and reinforce its “Neighbourhood First Policy” vis-à-vis Nepal amid rapid changes in the region.

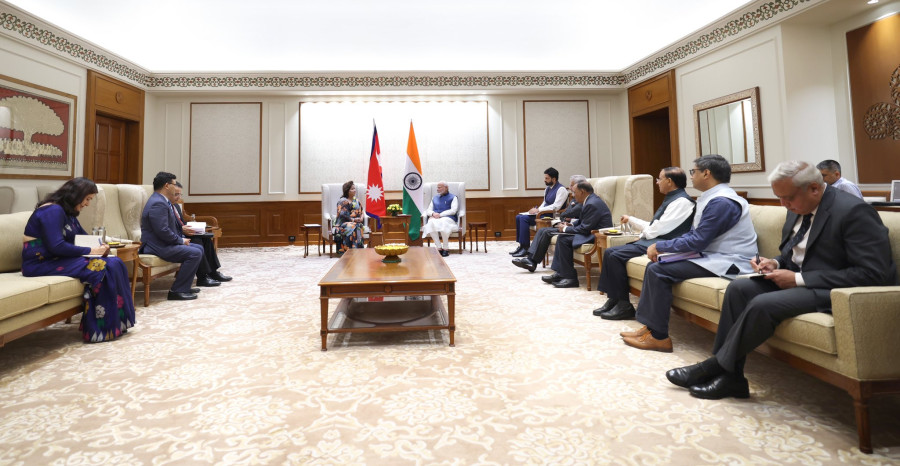

Reciprocation from Kathmandu was expected. A week later, Foreign Minister Arzu Rana Deuba flew to Delhi, carrying an invitation from her Indian counterpart S Jaishankar.

There was no dearth of optics—that Modi “agreed” to a meeting with Rana, reports suggesting it was a late-hour development, found quite some space in the Kathmandu media that described the one-on-one talks with the Indian prime minister as the icing on the cake.

Upon her return, Rana dubbed her visit “highly successful”, continuing the trend that her predecessors have duly maintained regardless of the outcomes.

Some cheerleaders were confused about what should be marked as the highlight of the visit—an agreement on the export of additional power to India or “the unexpected welcome” accorded by Delhi to Rana.

Text and context

Diplomacy has its own choreography—the almost simultaneous announcements of visits by two countries, followed by statements from both states upon the conclusion of the visits.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs put out elaborate statements, emphasising that “Nepal is a priority partner of India under its Neighbourhood First Policy.” Nepal’s “sagacious” Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrapped things up with brief statements, describing the visits as a continuation of the regular exchange of high-level visits between the two friendly nations.

Some may argue that substance matters more than text, but it’s the text that sets the tone for the context.

India’s Neighbourhood First Policy has often faced criticism at home and in the neighbourhood. In Nepal’s case, relations between Kathmandu and Delhi over the last decade have seen ups and downs, with ties at some points hitting rock bottom.

After ruling the world’s largest democracy with a majority for two terms, Modi’s third stint has a subdued mandate—he has coalition partners to “manage,” while the opposition has emerged as a strong force.

Frequent government changes in Kathmandu may have caused some inconvenience in Delhi, which often faces accusations of engineering them. However, its dealings with Nepal have largely remained the same, with just a little tweaking here and there in the modus operandi.

What happened in Bangladesh in the first week of August served as a wake-up call for Delhi.

In Bangladesh’s deposed prime minister Sheikh Hasina, India had found the most stable partner in the region. Delhi turned a blind eye even as Hasina ruled with an iron grip, and her party was accused of rigging elections. The democratic backsliding in the country of 170 million people was not much of a concern for Delhi, as it was content with its strong ties with Hasina.

It is surprising that Delhi completely ignored the fact that Hasina had entirely lost touch with the people. When mass protests reached a flashpoint, forcing Hasina to flee on August 5, Delhi was caught off guard by her “request to come to India at a very short notice.”

Hasina continues to be in India, her asylum pleas pending. For Delhi, the one-time most trusted partner could become a headache if she starts playing politics in her home country from India.

Having scant or no understanding of the ground reality in the neighbourhood has posed a serious question about India’s preponderance in the region.

A renewal of the Neighbourhood First Policy became urgent, and to start with, Kathmandu—a longstanding partner for Delhi—was naturally the best bet. And there is actually nothing wrong with that.

Subtext

India is well placed in South Asia—geographically and economically. But other states in the region are dealing with their own problems. Not much needs to be said about Pakistan. Afghanistan is turning into a pariah state under the Taliban. After falling into an economic abyss, Sri Lanka is now struggling to navigate through. Myanmar is fighting its own war. Not long ago, the Maldives declared “India out,” with a clear intent to partner with China instead. And in Nepal, there’s Oli, whose constant blowing hot and cold has been a source of irritation for Delhi in the past.

Nepal-India ties hit a low in the aftermath of the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015. India’s terse response and border blockade worked as a glue for Nepal’s ever-squabbling parties to align together, and they turned to China. For some like Oli, it became a tool to stoke ultra-nationalist—largely read as anti-Indian—sentiments.

For India, China’s growing influence in Nepal has snowballed from a minor inconvenience into a constant vexation. It’s not that Nepal has made great strides in terms of trade, transit and power transmission deals with China, but Beijing has deftly employed wolf-warrior diplomacy, evident from its diplomats suddenly coming out of their cocoon, which is not to Delhi’s liking.

The renewed push for pending projects and the recent signing of deals in power trade are part of Delhi’s exercise for deeper engagement with Nepal.

Delhi seems to have learnt from Bangladesh that investing in individuals can be counterproductive and that it must abandon its old-style tactics of engineering regime changes.

Nepal, India and South Asia

As India works on lessons learned, Nepal needs to figure out its course of action. Nepal’s foreign policy is hamstrung by politicians’ petty interests. Nepali politicians will do well to seek to maintain relations on par while attempting to diversify and promote trade and relations by keeping the people’s interests at the centre.

It’s a good gesture on the part of India to agree to buy additional power from Nepal, but the caveat that it would do so only if it is produced from projects with no Chinese involvement is simply bizarre.

The euphoria over Nepal selling power is also a bit exaggerated. For one, it still buys electricity from India during the dry season. And two, a singular focus on exporting power does not bode well for any country. Bangladesh stands as a great example.

In recent times, a simple utterance of SAARC is most likely to receive jeers and mocking. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has not met even once in the last decade.

Even with no immediate tangible results, the regional bloc, which will turn 40 this year, can serve as a good platform for dialogue and negotiations on many issues, enhancing understanding of the neighbourhood and avoiding a narrative vacuum.

The SAARC process has been stalled largely because of India. Nepal, as the chair, has not been able to exert enough leverage to push the process forward.

India is expected to expand its outreach in the neighbourhood, and it’s incumbent on Nepal to pursue its foreign policy in its own larger interest. After all, in this new world order, interests take precedence over anything else.

A hostile neighbourhood is not in India’s interest, and an overly concerned and suspicious India is not in the region's interest.

It’s time for Nepal to step up to the plate.

16.67°C Kathmandu

16.67°C Kathmandu