Fiction Park

Confronting the solitude in festivities

In a village, an old man clings to memories of his sons, hoping they will return. But as festivals approach, he knows he’ll face the holiday alone.

Sugam Gautam

The old man let out a long sigh, got up from the veranda, and walked toward the edge of the porch, from where he could see a bazaar named Besithumka. That was where his two brothers lived with their respective families. The village where the old man lived exuded an aura of haunted hinterlands, with every family locking their houses and moving to the bazaar. Now, the old man saw only his wife—a short, greying woman waiting for the inevitable.

At night, the old man was accustomed to hearing three different sounds—the hooting of wolves, the wheezing of his frail wife, and his own long, painful sighs. A jeep or two would ply the road below the house when the weather was favourable in the afternoons. The old man no longer complained about the dilapidated road to his wife. One day, while sipping their tea, his wife had jokingly said that he had finally lost interest in whining about the road. At first, he sighed and said, “Our sons won’t return to us even if the authorities blacktop the road.” A silence hung between them, and their lashes dampened.

The nearest house where people still lived was about 100 meters below the old man’s home. He assumed they were not as downcast about living in this isolated village. His assumption stemmed from the belief that families who lived together were never filled with melancholy. Outsiders would be wrong to assume that the old man lived in poverty. Both his sons were well-off, and on top of that, their children were earning decent money abroad. The old man made enough for them by performing minor poojas in the next village.

Some twenty years ago, when his sons were still young, he thought everyone would always live under the same roof—that they would never leave, even if they scattered temporarily to earn their living. When the younger son left for the city to open a shop, the old man clung to the hope that the elder son’s family would stick around. The elder son had been recruited into the police force, and his wife and son used to live with the old couple. But after saving enough, the elder son bought a piece of land in the southern part of the country, built a house there, and finally migrated, leaving his parents in the village. Even though the son had offered to bring his parents to the new house, there was no way the old couple would abandon their property and move to an unfamiliar place. The son should have known better.

As for the younger son, his business picked up, and within a few years of opening his grocery shop, he had established himself as a successful businessman in the neighbourhood. Rumour had it that he had bought as many as six pieces of land in Pokhara. However, his house was not as far as his elder brother’s; it was in the same district, some kilometres from the village.

The younger son had also proposed to his father that he come and stay in his mansion-like house, but the old man doggedly announced that he would not leave the place that had witnessed his life. In the next village, people talked about how those two sons had neglected their parents, saying it would have been better if the couple hadn’t given birth to such rascals. But it was the greatness of the old man that he always spoke in defense of his sons. “They are quite busy with their chores. My younger son has bought new land in Pokhara. The elder one has installed a rice factory in Madhesh,” he would boast to the people of the next village.

People would nod as if appreciating his sons, but when the old man walked away from the gathering, they would curse the sons, who, in the villagers’ opinions, were unworthy of their father’s love.

Every week or so, the old man, with a weathered bag slung over one shoulder, would trudge down the hill and visit his brothers. There was always something to offer his brothers—sometimes he would appear with thick, pale cucumbers, and other times with seasonal fruits he harvested himself with his gnarled hands. Both brothers were generous, for they often visited him in the village.

When the old man was done meeting his brothers in the bazaar, he would climb a bus that ferried him to where his younger son’s house was. As the bus neared his station, he always had that sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach. Would his son feel ashamed of his father if some high-profile guests were at the house? Would his daughter-in-law find his visit unnecessary? The kids would be gone to school, so he couldn’t meet them.

“Namaste, buwa!” the daughter-in-law would flash a perfunctory smile as if it were reserved for the old man. The son would escort him upstairs, the floorboards creaking under the old man's weight.

“How is aama?” The question was always the same; the concern, however, was never genuine. If he truly cared about his mother, he wouldn’t wait until Dashain to visit the village. It was the last Dashain when he had been to the village and the last time he had seen his mother because her breathing ailments kept her from visiting him. And the son wouldn’t care to go to the village and ask his mother how she was doing.

For someone who had spent his whole life in the village, the sophisticated setting only evoked uneasy feelings. After sitting on the couch for an hour, the son would come up with a can of juice and slide it into his father’s backpack. This act of stuffing the juice inside the bag indicated that it was time for the father to return to his own house, where his wheezing wife would be waiting for him, where roti would be made out of soft flour for his delicate teeth. Once home, the old woman would ask about his son, and he, masking his disappointment, would say that the son’s business had flourished even more.

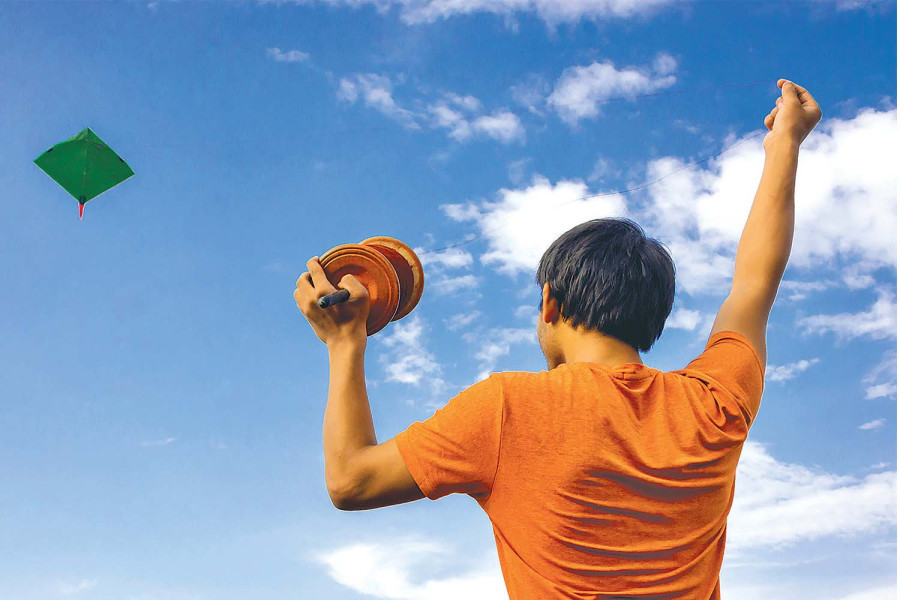

Now that Dashain was around the corner, people in the next village had started gathering with their families. From the porch, the old man peered at the next village perched on the nearby hillock. Youths in that village had installed swings like they did every year. Kites were soaring in the sky. The echoes of laughter lingered in the air, and it was as if the people in that village were benchmarking the celebration.

However, it was hard to tell if any grand festival was nearing in the old man's village. Only two houses were occupied by people, and the rest were home to stray dogs and mice.

“It has been four years since Thule (elder son) hasn’t come to visit us. Prakash (younger son) also doesn’t seem to care. It was last Dashain that I saw him,” the old woman murmured through her tears as they sat by the fireplace.

The old man couldn’t afford to get emotional and weep because he was his wife’s sole pillar. If the pillar itself collapsed, then what would remain? It was the day of Fulpati, but it no longer mattered which day it was for the old couple. The old man’s brothers were busy with their own families, and it was obvious that they would come to the village only on the day of Tika to receive blessings from their elder brother. Last year, when he had called his son in Madhesh, the son, in a low voice, had apologised for being unable to come.

“The son has a fever,” he had said. Two years ago, the daughter-in-law was affected by dengue. Three years ago, it was the son himself who claimed to have a migraine and thus had said sorry to his father. As for the younger son, who was at least not far away, the old man knew he wouldn’t come before the day of Tika. Now if he called his son in Madhesh, he was certain that his son would make up a story about someone suffering from one ailment or another. He was so certain of this.

What good is Dashain for them anyway? Even the day when people put Tika was like any other day for the old couple. The sons’ families and his brothers' families would come by and leave before sunset without staying the night. And then it was just the old man, his wheezing wife, and the emptiness left behind by those visitors. The old wife couldn’t remember the last time any guest had stayed overnight.

But right now, as dusk set in and the crickets chirped more prominently, the old man picked up his phone and dialled his son in Madhesh, the answers already echoing in his ear before the phone was picked up.

Gautam is a writer from Pokhara.

27.16°C Kathmandu

27.16°C Kathmandu