Health

Suicide is a big problem in Nepal but not many are talking about mental health

The government needs to invest in operating 24-hour suicide prevention helplines across the country, say mental health practitioners.

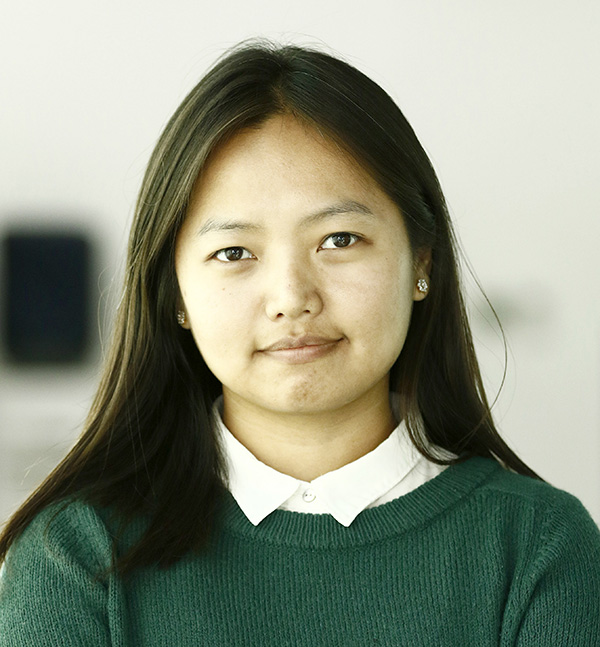

Tsering D Gurung

On Tuesday morning, the body of 45-year-old Bacchu KC was discovered on the second floor meeting hall of the National Planning Commission building in Singha Durbar. KC had poisoned himself, leaving behind a suicide note.

KC’s suicide is the latest in a string of such deaths. Over the past two months, four public officials, including KC, and one journalist are believed to have taken their own lives.

“Suicide is a major health concern,” said Basu Dev Karki, a psychiatrist at the Mental Hospital in Lagankhel. “Police data shows that the number of people committing suicide is increasing, but the actual number may be even higher, given that not all cases get reported to the police.”

Over 5,000 Nepalis commit suicide every year, according to a review of the Nepal Police’s five-year data, which show a steady rise in numbers. The majority of such deaths involve hanging.

Globally, suicide was the 18th leading cause of death in 2016. According to the World Health Organization, 79 percent of suicides occurred in low-and middle-income countries. Suicide is also the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15-29. Several studies based in Nepal show that a majority of the individuals who attempt suicide fall inside this age bracket.

“We still do not acknowledge mental illness as a serious health issue,” said Parbati Shrestha, project coordinator at the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal, which has been conducting suicide prevention programmes across the country. “And this is why as a society, we often end up ignoring warning signs from people who are suicidal.”

Contrary to news reports that often present suicides as being caused by a single event, Shrestha said there are multiple factors behind an individual’s decision to end their life.

“Suicide is complex, driven by a combination of factors,” said Shrestha. “Reporters usually tend to focus on one cause, for instance, loss of a job or property, but research has shown that no person decides to commit suicide for one reason alone.”

According to Shrestha, reporting suicides in such a manner reduces the complexity of the issue and presents a simplistic understanding of the health problem. Additionally, irresponsibly reporting suicide incidents may risk contagion, a phenomenon where suicide takes place as a result of the media’s reporting on suicides, warn several pieces of research.

The risk of contagion increases when the story describes the suicide method, uses dramatic/graphic headlines or images, and sensationalises or glamorises a death, according to Reporting on Suicides, an initiative to provide recommendations for journalists to responsibly cover suicide.

Reporters should refrain from describing the suicide method, describing the contents of a suicide note, and concluding that suicide was driven by a single event, according to multiple guidelines on reporting suicides.

“There is really no need for a journalist to describe how a person ended his or her life,” said Karki. “This does not add any value to the story. Instead, focus should be on spreading messages of help and support.”

Nepal currently does not have a national strategy on suicide prevention. As a result, no concerted efforts have been made to address this growing mental health issue at the national level. Programmes aimed at suicide prevention are primarily led by mental health professionals and non-governmental organisations, according to a 2018 paper published in the Asian Journal of Psychiatry.

One of the first steps towards preventing suicide would be to develop a reliable national database, say researchers. Several studies on suicide prevention in Nepal have highlighted the need for a reliable national database in order to truly identify the burden, determinants and distribution of suicide in the country.

“The current scattered and disconnected data-keeping system needs to be reframed,” recommended the authors of a paper titled Suicide burden and prevention in Nepal: the need for a national strategy. “The capacities of health facilities need to be strengthened and they should be identified as the main channel for the suicide data registry, in coordination with the law-enforcement and administrative mechanisms,” the paper reads.

In the absence of a reliable national database, police reports have become the key source of information on suicide. This has created its own problems.

While police data show that there has been a steady rise in the number of suicide cases, the World Health Organization’s estimates point to a decline in the rate of suicides in the past decade. According to WHO’s estimates, the suicide rate in Nepal declined by nearly half—from 15.5 per 100,000 in 2005 to 8.8 per 100,000 in 2016.

The WHO calculates its estimates based on a number of factors, including police reports, community-based studies, and trend reports.

The government also needs to invest in operating 24-hour suicide prevention helplines across the country, say mental health practitioners. These helplines should be equipped to not just offer counselling but should also include an intervention mechanism.

“The government at all levels has pledged to allocate a budget to suicide prevention programmes, but there needs to be a comprehensive national strategy to guide these initiatives to effectively tackle suicide,” said Karki.

At the moment, there are only four helplines that are run by hospitals and non-government organisations. But these helplines, some of which do not offer 24-hour service, are limited in their reach and effectiveness.

“The problem right now is that helplines are not equipped to help people from far corners of the country,” said Shrestha. “A helpline is not effective if we’re always asking the callers to come to where we are. We should be able to go to them.”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the following helplines.

TUTH Suicide Hotline: 9840021600

Patan Hospital Helpline: 9813476123

TPO Nepal Crisis Hotline: 1660 010 2005

Mental Health Helpline Nepal: 1660 013 3666

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

22.64°C Kathmandu

22.64°C Kathmandu