Interviews

Reduced sentencing was included to remove mistrust between warring sides

The amendment has complied with over 95 percent of the top court’s directives.

Thira Lal Bhusal & Binod Ghimire

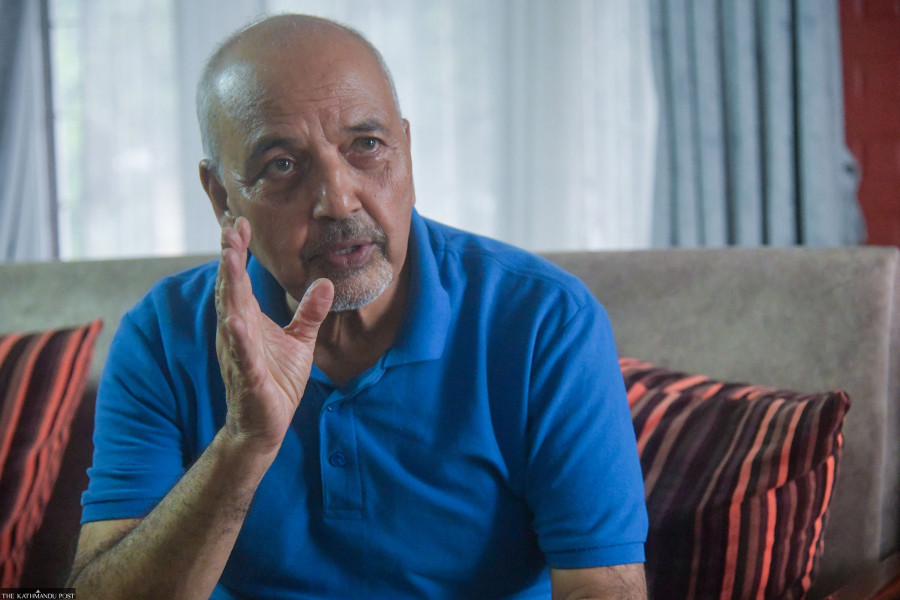

The Federal Parliament last month passed the bill to amend the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act. Political parties displayed exemplary unity in the course of endorsing the bill, which was promptly welcomed by the international community. If this undertaking succeeds, the remaining tasks of Nepal’s nearly two-decade-long peace process will be completed. In this context, the Post’s Thira Lal Bhusal and Binod Ghimire sat down with constitutional expert and former lawmaker Radheshyam Adhikari of Nepali Congress, who has over the years been closely involved in Nepal’s transitional justice process.

As a legal expert, how do you see the latest amendment in the transitional justice Act?

Looking at it from a legal perspective, the Supreme Court’s order given in this context is the major basis. The amendment has complied with over 95 percent of the top court’s directives. There is one more context we can refer to. The government in 2018 had prepared a ‘zero draft’ on this issue. The international community had expressed their reservations on certain provisions. Most of the contents of that draft have been retained while addressing those reservations. There are some major improvements. The amendment has taken a more liberal approach to victims’ rights. For instance, the draft had only said that the victims would be consulted for reconciliation but the latest amendment made victims’ consent mandatory.

If a victim doesn’t want to give consent, he or she can go to court. This is a major change. Likewise, the draft had said the verdict of the to-be-formed Special Court [with a mandate to hear and decide the transitional justice related cases] would be final. But the amendment has allowed the dissatisfied side to appeal in the Supreme Court. There is a plan for a separate fund to carry out transitional justice related tasks so as to ensure fiscal autonomy for the two transitional justice commissions. This process needs fiscal as well as administrative autonomy.

You just mentioned that the new Act has complied with 95 percent of the top court’s directives. Could you elaborate on the remaining five percent?

I meant to say that the amendment is closer to the court’s directives. I can’t say it is 100 percent because even they [the Supreme Court justices] at the time said ‘so and so’ should be done on a hypothetical ground as so many things were still evolving. Now, some issues might have become redundant. But most of the things have been addressed. See, first, we should have conceptual clarity. There is a fundamental difference between retributive justice and transitional justice systems. In retributive justice, cases are decided by regular courts based on existing laws while in the transitional justice system we have to look into political, social as well as cultural aspects. This is the internationally accepted approach.

The amendment has included a provision of up to 75 percent reduced sentencing. The attorney general, who works for the government, is mandated to recommend this. Isn’t this akin to directing the court? Wouldn’t it instead be prudent to leave that to the court?

If that were not done, there would be mistrust and the process may not have gotten sufficient support from the warring sides of the past. In such a scenario, the process may have again failed. A supportive role of the stakeholders will be crucial. Of late, I often urge the victims to cooperate with the process; otherwise it will remain a never-ending process. It’s already too late. So, now we should be pragmatic. We should carry out things on a priority basis. Finding and respecting truth are the first and second priorities. The option to go to court is there, if someone wants so. The fourth priority is reparation. The goal is to establish that no one will need to take up arms and resort to violence in Nepal again. Now, most of the stakeholders are positive about concluding this process. The international community has in fact asked us what type of support we need.

It is said the role of Desmond Tutu, who led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa, was crucial for the success of the country’s transitional justice process. Do you think the personality of the heads of the commissions will be vital in our case as well?

Leadership definitely matters. In Colombia as well, a person of similar stature, who is respected by all sides in the country, led the process. So, the leadership and composition of the commissions will matter. The commissions should be allowed to work and make decisions on their own.

There are nearly 64,000 complaints with the TRC and around 2,400 with the CIEDP. How should the commissions carry out their task? Will they deal with each and every case individually? What are international practices and what is a broader conceptual understanding in our case?

It is too early to talk about the working modality but I believe most cases should be dealt with in a representative way. But cases of serious rights violations will enter the prosecution stage. Producing sufficient evidence to prove the crimes, however, will be challenging. For instance, some rape victims may not be able to name the perpetrators. They were raped but couldn’t even recognise the perpetrator. In such a case, the state should respect such victims and provide reparation to them. Some complainants may choose not to continue with the cases. Before determining whether certain cases are serious or not, each file has to be checked at least once. So, the commissions need a large number of investigating officers. Field offices need to be set up based on the number and nature of complaints.

What kind of involvement of international agencies may be needed for this process?

It will certainly need the involvement of international agencies. Nepal’s peace process is basically home-grown but we will also seek support and expertise from international agencies, as we did in the past. We never work in isolation but the areas where we need their support will be decided only after the commissions start their work. We need international experts for certain specialised tasks, such as conducting DNA tests and exhuming bodies buried during the insurgency.

The way the international community promptly welcomed the new amendment, it seems that the government and political parties were working in close consultation with them. Is that so?

As far as I am informed, everything was done by Nepalis. But there was communication with the international agencies. They had earlier expressed their concerns on the ‘zero draft’ and the issues have been addressed. Therefore, they promptly welcomed it. They obviously are involved indirectly because it is a matter the international community is closely watching. But now we may need their direct support to carry out certain specialised tasks.

Why didn’t the amendment even mention the use of child soldiers, crime against humanity and war crime?

It is a matter of serious consideration as to whether our cases fall under the definition of serious crimes such as crime against humanity. The commissions will study this aspect as well.

Don’t you think the provision of reduced sentencing and overlooking of certain legal aspects may promote impunity?

Even now, inmates get a waiver of around 50 percent under the regular legal system. So the provision to reduce sentences is already there.

But such sentences are reduced only after serving for a certain time and demonstrating good behaviour. Shouldn’t we have adopted a similar approach in this case?

Transitional justice system should be seen a bit differently. Here, I give you an example. In Colombia, the TRC of the country summoned the seven secretariat members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). They were first briefed about the charges registered against them. They admitted that they committed the crimes. Then, all of them were acquitted because they spoke the truth. The TRC in Colombia gave priority to finding the truth. If someone showed honesty and cooperated in finding the truth they wouldn’t be punished. But they increased the penalty for those who tried to mislead them through falsehood.

Can we say our process is a bit driven by a reparative approach?

I again stress that we should look at the transitional justice process differently than how we look at the retributive justice system. It needs a different law, different court and a different jurisprudence.

It takes years of rigorous work to complete this process and firm commitment of major political forces is vital. Frequent changes in coalition and unpredictable relations between the political forces is our reality. Don’t you think such instability may hamper this process?

This time around, the role of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli is very positive. Chiefs of the three biggest parties, while addressing a parliament meeting, have expressed their commitment to make this process successful. Their unity on this matter is important. Not only them, all the political parties represented in the federal parliament, except one lawmaker from a fringe party, have supported this amendment. It has thus become a national issue. I hope this consensus will remain intact while picking officials for the commissions and taking the entire process to a logical end.

Given your expertise and involvement in this process, you are being seen as a strong candidate for the TRC chair. What is the reality?

I have nothing to say as no one has talked to me about this.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu