Interviews

Even 5 percent economic growth looks ambitious

The ratio of capital formation to GDP has been consistently decreasing since 2018. This makes growth difficult to achieve.

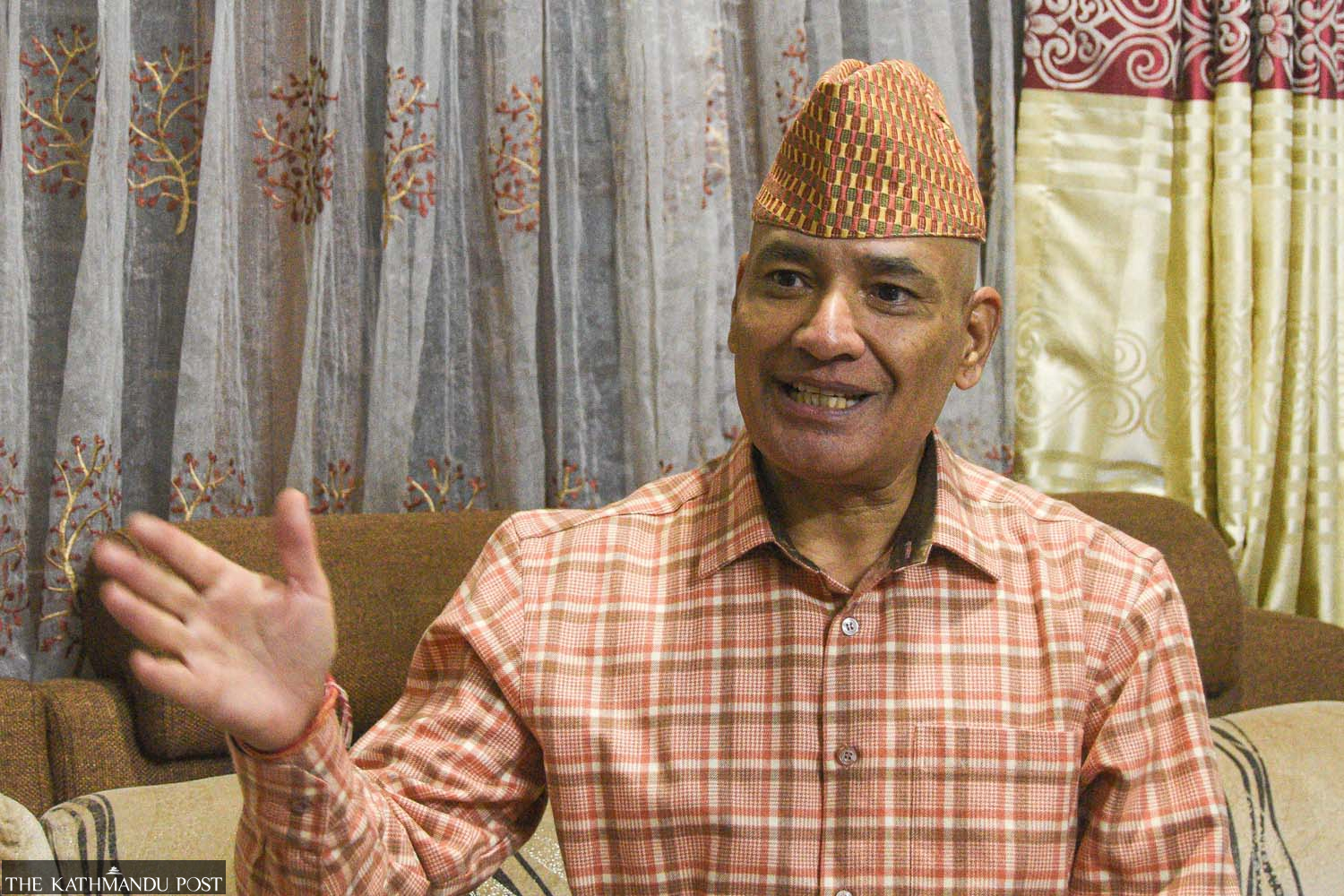

Thira Lal Bhusal

Nepal’s economy that has been facing one after another setbacks since the 2015 earthquake has been struggling to bounce back. Last week, two international agencies—the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB)—announced that Nepal’s economy was poised to improve in the upcoming fiscal year. In this context, the Post’s Thira Lal Bhusal sat down with Nara Bahadur Thapa, former executive director of the research department of Nepal Rastra Bank, to discuss the current state of the national economy.

The ADB, in its report last week, anticipated Nepal’s economy to grow by 4.9 percent this fiscal. A few days earlier, a visiting IMF team also painted an improving picture of Nepal’s economy. How do you see these projections?

Nepal’s economic growth in the past 2-3 years has remained below 5 percent. But successive governments in their fiscal budgets have been setting the target of 6 to 7 percent growth. Also, the budget this year has aimed for 6 percent growth. In the meantime, two donor agencies have painted an improving picture of our economy. The ADB has anticipated 4.9 percent growth. Also, the IMF’s team that visited Nepal on a fact finding mission has projected better prospects. They expected better yield from the agriculture sector as Nepal is witnessing more rains.

Last year, the growth of agriculture was 3 percent. Now they expect the sector may grow by 3.5 to 4 percent and that may lift overall growth. They have cited improvement in tourism and increased energy export as other bases. Based on these grounds, the ADB has projected 4.9 percent economic growth.

But even the target of 5 percent growth looks ambitious if you analyse economic data available as of now and the steps taken by government agencies. We have witnessed more rain but that doesn’t always do us good. More rain in the late monsoon often damages paddy at the time of harvest. Second, the heavy monsoon has caused huge losses in our infrastructure such as roads and bridges that are vital to keep the daily lives and trade running. This may impact potential economic growth as some vital highways and roads have been badly damaged. These factors may pose a challenge in achieving the targets set by the government and donor agencies.

Another important factor is that the ratio of capital formation to GDP [gross domestic product] is consistently decreasing. It was 33.8 in the fiscal year 2018-19, it decreased to 30.5 in 2019-20, to 29.3 in 2020-21, 29.0 in 2021-22, 25.1 in 2022-23 and 24.5 in 2023-24. How can we expect economic growth when capital formation keeps decreasing. We can’t achieve 6 percent growth without first improving the situation of capital formation.

Capital formation in the private sector is on a decline and the government hasn’t been able to boost it. On the other hand, capital expenditure was lower in the past fiscal year in comparison to the previous fiscal. There is no strong sign of increasing capital formation even in the coming year. This is because the government has failed to collect revenue as per its own target. The revenue collection ratio is falling. It has come down to 18 percent of GDP, from 22 percent not so long ago.

With this, the government’s funding capacity is continuously declining. It has failed even to fulfil its own duties. For instance, it hasn’t been able to pay health insurance bills and or the contractors. Similarly, credit offtake from private banks to the private sector has not increased from 6 percent. It used to be around 15-16 percent. Also, no substantive initiatives have been taken to improve productivity. For this, government agencies have to cut red tape. The private sector isn’t optimistic. We are talking a lot but not working seriously to lay a strong ground for growth.

What are the signs that private investors are pessimistic?

There is enough liquidity in the banks, and the interest rate is decreasing, but the private sector is not borrowing. Bankers say there is no demand from the sector. This indicates pessimism. None of the big business houses have launched any big projects in recent times. The government talks a lot about the energy sector but it is not doing power purchase agreements (PPAs) with hydropower project developers. We aren’t doing enough to realise the goal of exporting 10,000MW electricity to India. This shows no serious effort is being made to initiate reforms. The capital market has required some urgent reforms. But the government hasn’t appointed office bearers in the regulatory body for the past seven months. The government hasn’t given permission to issue IPOs and FPOs. Hence, the government is keeping two important sectors—energy and capital market—on hold. All these trends and activities suggest it will be a challenge to achieve even moderate economic growth.

You pointed to the policy hurdles but the multilateral agencies have hailed the government for policy reforms. The IMF in its statement has welcomed recent amendments to various laws and the ADB has welcomed “the cautiously accommodative monetary policy”. Don’t these statements reflect reality?

While making their positions public, the international agencies follow certain norms and criteria. First, they take macro pictures such as the government’s commitments. They take the pledges made by the government in the investment summit seriously. They think the commitments will be implemented. Second, they don’t want to irk the host country by presenting a bleak picture because they are diplomats. They point out possible pitfalls during bilateral and table talks but present themselves diplomatically while making their official statements public.

Remittance, tourism and energy export are taken as major bases for economic growth but all three depend on external factors. How reliable can the projection be?

Without trading and increasing exports, we can’t progress economically. We need to export to increase production and create jobs. Export is an engine of economic growth. Anyhow, we must increase exports. About your query, the government should tackle such things by strengthening relations with the countries concerned and devise policies and strategies accordingly.

Our economy is increasingly dependent on remittance. How risky is it in the long run?

Remittance has become a boon for our economy. It has played a tremendous role in poverty reduction. The first Nepal Living Standard Survey (NLSS) conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS)—now the National Statistics Office—in 1995-96 showed 42 percent Nepali population living below the poverty line. The latest [fourth] living standard survey has shown the poverty level at 20 percent. It wouldn’t be possible without remittance. Therefore, we can’t undermine the role of remittance in this social transformation.

Were not the government’s plans and policies responsible for this achievement?

The government role would not have been enough. What government policies have created jobs in Nepal? Are there any schemes worth mentioning? The industrialisation hasn’t increased. It is the industrial sector that creates jobs but the share of the manufacturing sector has come down to 4.87 percent in total GDP. Some years ago, it was nearly 9-10 percent. It shows our economy is being deindustrialised. How can we reduce poverty without providing jobs to the youths? Thus, foreign employment played a vital role in poverty reduction. Second is the role of remittance in maintaining foreign exchange reserves, which is essential to buy things from abroad. We have sufficient foreign exchange reserves because of remittance.

Information Technology is now projected as a promising sector in creating jobs and transforming Nepal’s economy. How realistic is this expectation?

Four fields can be taken as promising sectors in Nepal—agriculture, tourism, IT and hydropower. The IT sector certainly has a bright future. As our country is land-locked, we have additional challenges in merchandise exports and we can’t be competitive. The IT sector won’t have that barrier so it can be competitive in the international market. But for that the government has to formulate IT-friendly policies. For instance, if a Kathmandu-based Nepali firm wants to sell services in the US, Europe or any other international market, they need liaison offices in those countries. Otherwise, they can’t be competitive and grow. But the government doesn’t provide foreign exchange for them to expand their business abroad.

Without this policy reform, Nepalis can’t compete with IT companies from other countries. Similarly, foreign companies need to come and work here so that Nepali youths can learn from them. Foreign banks came to Nepal and Nepali bankers learned. Now Nepali banks are doing good. But our policies aren’t favourable for foreigners interested in setting up IT firms. Also, well-trained IT workers are in shortage. We are progressing but we have to put in extra effort to make transformative changes in this sector.

The cooperatives’ scam has emerged as a serious issue. What impact may it cause in the national economy if it’s not resolved soon?

The cooperative sector played a vital role in creating financial inclusion in our economy by making 7.3 million people its members. Those who couldn’t do their regular transactions with banks were engaged with cooperatives. If that sector collapses, our state of financial inclusion will decline too. Second, they were major financiers for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME). Cooperatives are directly linked to entrepreneurship through MSMEs. They played a role in making interest rates of banks more competitive as well as banks and financial institutions were under pressure by the interest rates offered by cooperatives. Now they won’t feel the pressure.

In this context, many people may resort to informal transactions. According to the 16th periodic plan, nearly 50 percent of Nepal’s economy is informal. We are under pressure to reduce the portion of the informal economy. But the crisis in the cooperative sector may increase the informal economy as those who were involved in cooperatives, which is a formal sector, are likely to do informal transactions with traders or other individuals.

Cooperatives are not well regulated and there are anomalies but they are registered in a government agency, pay taxes, have offices and a record system. They brought people in far-flung villages under a formal channel. If the depositors resort to individual transactions, their money will be unsafe. The constitution accepted them as one of the three pillars—along with the government and the private sector—of the country’s economy. The sector expanded its network where there were no economic activities from the government and private sectors. For instance, the government was providing certain services such as distributing fertilisers, crop seeds, sugar through cooperatives. People will now be deprived of these services. Also, the commercial banks might face complications due to the domino effect of the cooperative scam. For instance, if the government seizes the land put up by a cooperative as a collateral in a bank and sells it to return the deposits, the bank might be in trouble.

It is also said that cooperatives were becoming platforms for money laundering. How serious was the problem?

Cooperatives didn’t seek a source of money from the depositors while accepting big deposits. They weren’t affiliated to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) of the central bank and the Anti-Money Laundering/Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT). Therefore, there is a problem of money laundering. It can be resolved when they get affiliated with the FIU.

What initiatives should be taken to address the problems seen in the cooperative sector?

A powerful regulatory authority should be established without delay. The authority should work as a dedicated agency to clear the mess. Then, AML/CFT provisions should be implemented, a credit information centre should be set up and a debt recovery tribunal formed, and deposits guaranteed. The concept of self-regulation isn’t enough. These financial infrastructures are essential.

17.13°C Kathmandu

17.13°C Kathmandu