Life & Style

Family hostility, social obstacles: How this queer couple’s union survives hardships

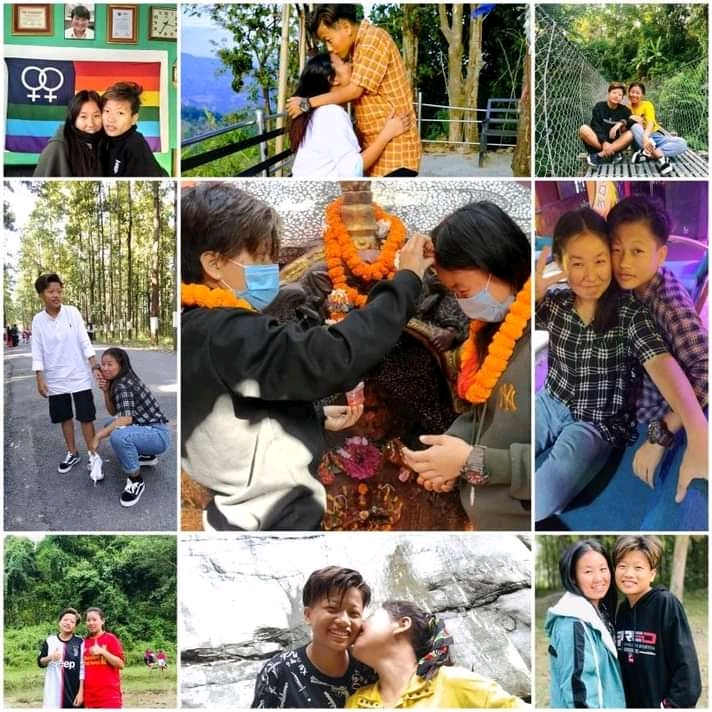

Lorax Rai and Madhusha Limbu struggled for years to have their relationship accepted.

Urza Acharya

It was love at first sight. When Madhusha Angthupo Limbu saw Lorax Rai at a football practice session, the two immediately clicked with each other. As they got talking, Madhusha’s feelings grew stronger. But she was in denial, she said. “I didn’t know whether what I felt was just a friendly affection or a romantic attraction.” Before meeting Lorax, Madhusha didn’t know she was queer.

Now, Madhusha and Lorax, who is a transgender man, have been married for three years. They live with Lorax’s family in Beldangi refugee camp in Jhapa. When they began their relationship back in July 2019, their lives took a drastic turn, resulting in two police cases, death threats, and an elopement to Kathmandu that left them vulnerable both mentally and financially.

Though Nepal’s constitution guarantees the right to freedom and a life of dignity for gender and sexual minorities, it has not yet translated into societal practice, as queer individuals face discrimination, even violence at the hands of their own family members, the community and state institutions like the police. Some have also resulted in deaths, like in the case of Junu Gurung in 2019 and Ajita Bhujel in 2020, both of whom were trans women.

The existing laws for people of marginalised sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics (PoMSOGIESC) have been criticised for being archaic and limiting—as the ‘third gender’ label often fails to address the larger queer spectrum. Moreover, despite provisions, queer folks have been denied equal rights in terms of education, health services and financial opportunities.

How it all started

Lorax, who was assigned female at birth, has always identified himself as a man. He was born in Beldangi, Jhapa, and his family accepted his masculine presentation from childhood. “I dressed up like a boy and liked doing traditionally masculine things,” he says. His parents, unlike many families who are unaccepting of queer values, let Lorax be himself without prejudice or judgement.

Madhusha, who was born in a village near Beldangi, however, wasn’t so fortunate. When her parents found out she was in a relationship with Lorax, they were furious. “How can two girls be in a relationship? That’s what my family argued,” she says. After receiving threats and physical abuse, she ran away from home and joined Lorax at his home in Beldangi.

One day, however, both were summoned by the police, who revealed that Madhusha’s parents had filed a police case condemning the couple’s union. “Her family members threatened and intimidated us at the police station, demanding that we never see each other again,” says Lorax. During the confrontation, there were even instances of physical violence.

Kabita Tamang, the Koshi provincial coordinator of Mitini Nepal, an organisation that advocates for queer individuals, says that she can cite many examples wherein police cases are filed against queer couples. “Families often file kidnapping cases when, in truth, their children have run away from home because of abuse and discrimination they face for being queer,” Kabita says, adding that in the past, many LGTBIQA+ individuals were also sent to rehabilitation centres.

The police in Beldangi sided with Madhusha’s family, which resulted in them being forced to sign a written document agreeing to stay away from each other. Back at home, Madhusha would be beaten up frequently, so after a month, she returned to Lorax’s home.

Fearing for their lives, Lorax and Madhusha eloped to Itahari, where they stayed with a common friend Jewel Dhimal for a day. Then they met with Suman Tamang, a trans man, who hosted them for another day. “Both of them were scared and under a lot of stress,” says Suman, who runs a local organisation called ‘Sahara’ to spread awareness on LGBTIQA+ issues in Itahari of Sunsari and neighbouring districts.

It was Suman and Jewel who got them in touch with Mitini Nepal. “With Mitini Nepal, we learned about gender identities and realised we were not alone,” says Lorax.

Kabita says cases of elopement by queer folks aren’t uncommon. “We get several cases of elopements, many under-age,” she says. In the case of minors, the organisation often advises them to return home and finish their studies. If the threat is imminent, they are put in shelters.

“As both Lorax and Madhusha were legal adults, the organisation let them decide for themselves,” she says. After receiving some counselling, the couple decided to go to Kathmandu, looking for greener pastures.

Life in the Valley

The couple settled in Kathmandu in the winter of 2019. Madhusha found work as a waitress in a local restaurant. But life in the Valley wasn’t too kind either. Both were just students back in Jhapa; they had difficulties sustaining themselves in the city. Given the stress of running away from home and receiving threats, both suffered mentally. “I got sick so many times,” Lorax recalls. “I had difficulty breathing and eating. I wasn’t in a good place.”

According to a journal article published by the Nepal Medical Association, LGBTQI+ people are already at a greater reproductive, physical, and mental health risk, and the healthcare services offered to them are severely inadequate. One of the biggest obstacles to receiving healthcare services is the stigmatisation and discriminatory attitudes healthcare practitioners display, according to the article.

As Lorax couldn’t find or afford mental health professionals who understood his experience, living in Kathmandu proved to be one of the bleakest times of his life, he says.

Nonetheless, the couple decided to get married at a temple in Kathmandu on December 22, 2019. “That was one of the happiest days of my life,” Lorax says.

But that happiness wouldn’t last long. Unable to find proper financial footing and in light of Lorax’s worsening health, they returned to Beldangi to Lorax’s family home in February 2020.

Back in Beldangi

Back home, things were normal for a while. Lorax’s family welcomed their daughter-in-law with open arms, calling her ‘nani.’ But Madhusha’s family members were still angry. One day, while walking in the nearby bazar, the couple was stopped and harassed by a group of individuals sent by Madhusha’s family. Soon, the police knocked on their door again, announcing another police complaint had been filed against them.

Police referred the new case to Damak, says Madhusha. In Damak, the couple contacted Lead Nepal, an organisation fighting for LGBTIQA+ rights. Lead Nepal mediated their case with the police, arguing that both were legal adults—21 at the time—with the right to decide for themselves.

Rubina Nepal, a monitoring and evaluation officer at Lead Nepal, remembers that the incident was very difficult for both Lorax and Madhusha. “Lorax had been slapped a few times by one of the attackers,” Nepal recalls. “Death threats were being thrown about in the station.”

Sensing a danger to their lives, Lead Nepal crafted a minute at the police station stating that certain members of Madhusha’s family be held responsible should the couple be harmed in any way. It was only then that the agitating party backed off.

The complaint against Lorax and Madhusha was finally dismissed. After the verdict, Madhusha’s family disowned her. “They said I’d brought them shame and wanted nothing to do with me,” she says.

Calm after the storm

Three years later, their life has taken a happier turn. They can now love each other freely and without fear. Though it took a while for them to feel safe stepping out of the house, Lorax and Madhusha now roam around the bazar as a couple. As Lorax’s parents often fall sick, both take turns doing household chores and rearing the pigs.

The recent Supreme Court interim order to facilitate marriage registration for same-sex and non-heterosexual couples has them elated. Despite having married three years ago, their marriage was not legally recognised. “We’re now planning to register the marriage as soon as possible,” Madhusha says.

However, queer activists argue that the issue isn’t out of the woods yet. “The registration is temporary till the proper mechanisms are built. We’re just worried the government might not keep the end of the bargain,” says Suman Tamang.

Moreover, he believes that as long as queer couples aren’t given full equality in terms of marriage—from the registration, insurance, adoption, and even divorce and spousal support—biases against gender and sexual minorities will continue to persist in society.

Anurag Devkota, a human rights lawyer, says that the interim order is simply the stepping stone to ensure marriage equality for queer folks as the final verdict is yet to come.

If the final verdict rules for the legalisation of queer marriages, there would need to be an amendment to the Civil Code 2017 which dictates that a marriage is ‘concluded’ if a ‘man’ and a ‘woman’ accept each other as husband and wife. The use of gendered words like ‘man’ and ‘woman’ rules out the possibility of marriage between queer individuals.

9.88°C Kathmandu

9.88°C Kathmandu