National

They spoke up and they are receiving threats

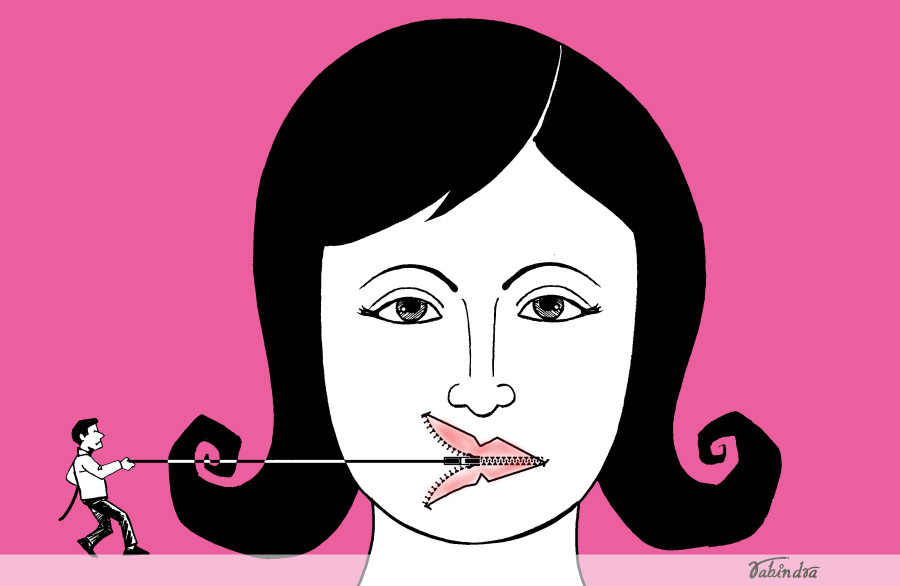

Harassment, death and rape threats, and bigotry against women are a silent epidemic affecting their right to speak up against issues, women activists say.

Samiksha Baral

On February 15, Anshu Khanal, a theatre artist who has been an active part of several recent protests against widespread cases of rape and violence against women in the country, was jubilant for her contribution to the movement.

“We will continue our fight till the last battle,” the 21-year-old artist had shouted after reading her poems in front of an audience of hundreds at the Tribhuvan University premises. She had been receiving accolades for her performances from her friends and those who know her. These words of praise were given either face-to-face or over the phone.

But not everyone was in a mood to congratulate her.

As soon as she turned on the internet on her cellphone while returning home that day, she saw she had been bombarded with hateful and violent invective comments. The deluge of derogatory comments online was in response to her previous performance during the Women’s March on February 12.

That march, a voluntary turnout of the general public in rage against rising cases of violence against women and girls, was attended by students, members of the general public, activists, human rights defenders and artists, among others.

Then, too, Khanal had put on a memorable performance. In a symbolic act, she performed as a girl who had been raped and murdered and her funeral procession was taken around the city.

“I was lying as if I was dead while I was taken around the city. I did not feel any pain in my body, but much in my heart and soul,” Khanal told the Post. “In those moments, I could feel the pains of my other sisters like Nirmala Pant, Bhagirathi Bhatta and every other girl who had suffered from such horrendous acts in the past.”

Her performance had been the highlight of the march. She was receiving a lot of praise as well as media attention for being bold to portray the tragedy of all those dead girls and women who had suffered from such a gruesome crime.

She had spoken to the media, unaware of what was coming her way.

“I felt like I was going to fall on my face as soon as I saw the comments on one of my video interviews,” said Anshu. “Though I used to get a lot of abusive comments earlier, those comments on the video were something beyond my imagination. It left me completely shattered.”

Not only Anshu but many girls and women who have come out on the streets and spoken for justice, demanding the government create a safer environment for them, have been abused online.

“Extreme defaming and demeaning on social media of activists, especially youths, are remarkably common these days. These threats come from those who are not willing to see changes in our society and do not support inclusion and strongly possess patriarchal beliefs,” Mohna Ansari, a former commissioner at the National Human Rights Commission, told the Post. “When young people and their perspectives are targeted, they will not have the courage to come out next time to speak up against discrimination.”

According to the Amnesty International report, 2018, violence and abuse experienced by women are often sexist and misogynistic in nature. Documenting women’s experience of violence and abuse on Twitter, what the rights group called, ‘Toxic Twitter’, it said such abuses on the microblogging site have become a far too common experience for women. The aim of violence and abuse is to create a hostile online environment for women with the goal of shaming, intimidating, degrading, belittling or silencing them.

Sapana Sanjeevani, another youth activist and an artist, recited a poem in the Maithili language during the Women’s March. She faced the same fate in the aftermath of her act.

“We are no longer tolerant like Sita and blindfolded like Gandhari,” Sanjeevani had said in front of thousands who had roared in appreciation.

Sita, the wife of the Hindu god Ram, is celebrated for her wifely virtues while Gandhari blindfolded herself because her husband Dhritarashtra, the king of Hastinapur, was blind, according to the Hindu epic Mahabharata.

Her poem challenging patriarchy imposed through Hindu practices was a representation of new voices coming out to shake the foundation of age-old patriarchy.

“I chose that poem to tell people that we are no longer going to tolerate oppression and we are going to speak against gender violence,” said Sanjeevani. “We are not remaining silent now onwards.”

But as soon as her reading of the poem was posted online and it went viral, Sanjeevani started getting threats—even rape and death threats.

From the Facebook account of Raju Jaiswal, Sanjeevani’s poster was made with a Rs 10,000 cash award for anyone who blackened her face. Those throwing vitriol at her said she had to be punished for making derogatory remarks about the Hindu society.

“I have already taken legal action against those accounts but I can do nothing about those hateful comments directed at me,” Sanjeevani told the Post. “I have now stopped reading comments on Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms.”

Most often, that’s the only alternative for targeted women and girls for speaking out. They tend to avoid using social media, at least for some time, if not forever.

In Nepal, 5,574 cases of online harassment were reported to the Cyber Bureau of Nepal Police between the fiscal year 2016-17 and 2019-20.

According to Baburam Aryal, a lawyer who specialises in cyber law, as per Electronic Transactions Act-2008, a person can face a jail term of up to five years for cases of online harassment but proper implementation of the law is lacking.

“Besides, in Nepal, women don't usually file complaints of online harassment as the legal process is a bit cumbersome and women don't want to reveal their identity,” he said. “The police must be pressured to do their work sincerely when it comes to online harassment.”

According to a 2015 UN report ‘Cyber Violence against Women and Girls: A Worldwide Wake-up Call’, one in three women will experience some form of violence in her lifetime and 73 percent of women have endured cyber violence. The report also states that women are 27 times more likely than men to be harassed.

“Social media gives people anonymity which gives such online abusers strength to continue harassing others. As one doesn’t have to go to the person and pass such comments, this gives the person the power to write abusive comments,” said Sudhamshu Dahal, assistant professor of new media and information technology at Kathmandu University School of Arts. “Until and unless efforts are made to rein these attacks on women, we won’t be seeing much change.”

Fear of potential abuses works as a prior-censor or a deterrence tool and gag individuals’ right to express their views, thereby encroaching on their democratic rights, according to activists.

“Online abuses also have an unhealthy impact on our democracy and if this issue is not addressed in time, there might not be a presence of women in the public sphere since those hiding behind the mask are aiming at them,” said Ansari. “Digital media should be used with discipline and those who violate it should be penalised.”

Case studies conducted by the Women’s Rehabilitation Centre showed that perpetrators are sometimes not punished because of a lack of evidence during the investigations. Also, many victims fear the consequences of speaking up against cyberbullying and they are also not aware of the kind of complaints they can file as evident from one case of Morang district studied by the centre.

Twenty-year-old Mahima (name changed) from Morang used to tolerate egregious behaviour like assault, verbal abuse and non-consensual sharing of an image to her because she was not aware of the law and did not believe that she could get justice even if she reported to authorities.

“We found that women across the district did not report cases of online abuse because first, they are not aware of the law and secondly they do not believe they will get justice even after filing a complaint since women are re-victimised,” said Shristi Kolakshyapati Pradhan, a programme coordinator at the Women’s Rehabilitation Centre.

Experts feel that a massive awareness campaign is needed to protect girls and women from potential online abuses and make laws more effective.

“In order to reduce the number of online abuses, the main solution would be a massive awareness campaign to educate people about proper internet etiquette and toxic online behaviour and formulating effective laws,” Dahal told the Post. “There are many instances where the police are not aware of new technologies while abusers are keeping up with technology.”

But others feel that the problem of online abuses of girls and women is the result of a deep-rooted patriarchal mindset in society.

“Women are not considered as human beings if you look at societal and cultural aspects of our society. The power-worshipping patriarchal society would like to keep us in prison, oppress us as much as they can. Society cannot bear seeing women being independent and speaking up,” said Pranika Koyu, human rights activist and a poet. “There are people who think that our laws have already guaranteed the safety of women in many aspects and women are more privileged than men. But women continue to be abused both at home and on digital platforms.”

According to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, discrimination against women includes gender-based violence, that is, “violence which is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately, and, as such, is a violation of their human rights.”

But youths like Khanal vow that they will continue to speak up against violence and discrimination against women. They have been performing and reciting poems against the system since the rape and murder of the 17-year-old Nirmala Panta in 2018, when thousands of people marched to the streets and appealed to the government to punish the culprits.

Despite the failure of the system to find and punish the perpetrators of the 2018 case, Khanal did not give up and she was on the streets again to demand justice for a 17-year-old schoolgirl from Baitadi who was raped and murdered on February 4. A 17-year-old boy was subsequently arrested in connection with the Baitadi rape and murder case.

But the battle has not been easy for women like Khanal.

“Existing oppressions towards women, transgender and queer people are made worse by digital violence,” said Koyu, the activist. “The victims, who have gone through so much mentally, have to bear the burden of financial resources and police doubting them and making it hard to even make use of the existing laws.”

For Khanal and others who dared to speak up, the effects of online violence can be seen in the offline world, causing significant emotional and psychological distress.

“No matter how much I tell myself that I am strong enough to deal with such things, deep down it breaks my heart and affects my mental health and productivity,” said Khanal. “We have been subjected to the same violence and threats we have been fighting against.”

22.65°C Kathmandu

22.65°C Kathmandu