National

How Nepali society silences gender-based violence survivors

Breaking the silence against abuse has been a challenge, especially for ‘urban’ women. Their hesitance can mostly be attributed to lack of support in their immediate circles.

Pinki Sris Rana

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Jivan Bhattarai, a counsellor at Women’s Rehabilitation Centre (WOREC) Nepal, got a phone call. At the other end of the line was a distressed woman seeking a way out of an abusive relationship with her husband.

The woman, in her late 30s, is from an affluent family in Kathmandu and has been married for several years now. Since the start of her marriage, she has been a victim of domestic abuse at home, she told Bhattarai.

“She did not disclose how long she’s been married but she had no support from her family and didn’t know how to deal with what was happening to her,” said Bhattarai. “I counselled her over the phone and told her that there are several ways she can go about handling the situation—from guided intervention with her husband to legal recourse—but she never got back to me after that phone call.”

WOREC receives a minimum of three calls every day from women who are looking for a way out of abusive relationships. But very few callers act on the advice they receive from counsellors, especially if the callers are from Kathmandu Valley, says Bhattarai.

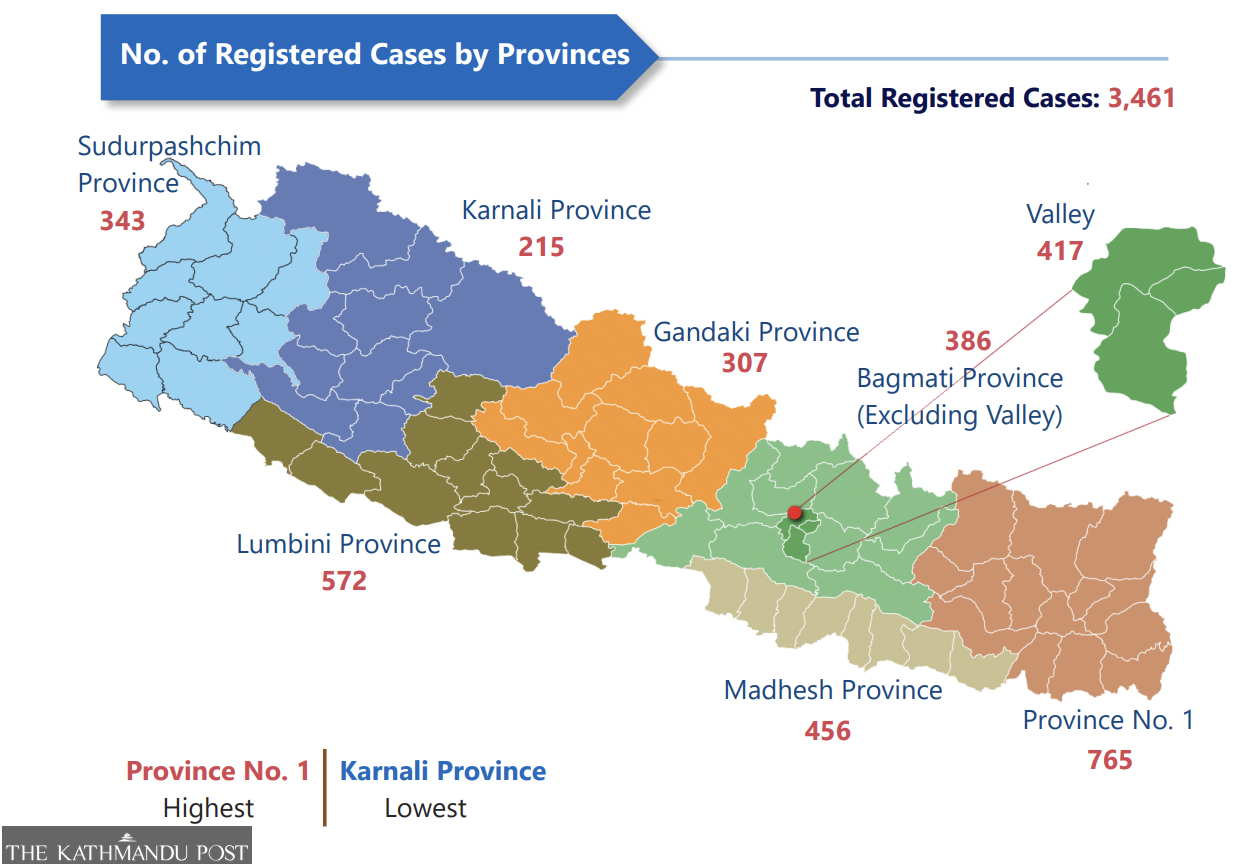

“Domestic abuse victims from outside the Valley are more likely to file complaints against their abusers compared to those from the Valley in similar situations,” said Bhattarai. “Out of the 1,813 gender-based violence cases recorded at WOREC in the current fiscal year [2021-22], only 76 were from the Bagmati province. The vast majority of domestic violence cases registered with us are from outside the Valley even though most calls we get for help are from women in Kathmandu. Most of them don’t take further action against their abusers.”

Registered cases of Gender-Based Violence (GBV) against women have visibly gone up in the past 25 years. This increase in cases is directly proportional to an increase in awareness and literacy in women and society, say experts. But even today, breaking the silence against abuse has been a challenge, especially for women who fall under the “urban” category. This hesitancy faced by women from economically advanced echelons of society who are educated and aware of their rights, can be attributed to the lack of support in their immediate circle.

In South Asian societies where the burden of upholding the family’s name and stature rests on women, it is difficult to speak out against one’s family, says Maheswari Bisht Rawal, chief of the Women Development Division of Lalitpur Metropolitan City. “The victims of domestic abuse in urban settings feel they have more at stake if they speak out. They stand to lose their status in society as their relationships are integral to their social identity,” she said.

According to the annual report of Nepal Police for the current fiscal year, after Province 1, Lumbini and Madhesh provinces, just Kathmandu Valley of Bagmati province registered the fourth-highest number of sexual violence cases (417). The data reflect cases of rape, attempt to rape, child sexual abuse, ‘unnatural intercourse’, abduction and murder cases from the Kathmandu Valley.

“But the number of domestic violence cases registered with the police is minimal,” said Inspector Mina Devi Rai at the Women, Children and Senior Citizen Service Centre (WCSCSC) of Nepal Police.

“Even if a domestic violence case reaches the police, the aggrieved party usually decides to ‘settle’ rather than seeking a legal course of action,” said Bhattarai from WOREC.

Rawal from the Women Development Division of the Lalitpur Metropolitan City, who in the early part of her career worked extensively with rural communities, says she thought gender-based violence only existed in rural areas due to illiteracy and lack of awareness.

“But that was decades ago. After I transferred to Kathmandu, I realised how wrong I was. I thought these issues didn’t happen in literate households, but even women in educated circles find themselves in such situations,” said Rawal. “Our division gets several phone calls a day from victims of domestic abuse in Kathmandu, where the literacy rate is high. But only a few decide to take legal action.”

One of the reasons why urban women find it difficult to speak up against gender-based violence is the understanding, or lack thereof, of what constitutes violence, says Rawal. “In popular narratives, violence only happens when one is physically abused. Limiting the definition of violence to physical abuse is limiting the understanding of violence against women,” said Rawal. “It takes a while for a woman to realise what’s happening with her is abuse.”

The lack of awareness in the urban areas, Rawal says, also stems from the absence of awareness campaigns targeted at the urban population.

In rural areas, local organisations to INGOs actively disseminate information about domestic violence which helps sensitise the women about the forms of domestic violence and available resources. “There are free services provided by the government to victims of gender-based violence. People in villages know about these services, but those in the city are unaware of the available help,” Rawal, who has spent the past three decades of her career on women’s development, told the Post.

The Ministry of Health and Population runs the One-stop Crisis Management Centre (OCMC) in coordination with government hospitals, but most victims of domestic abuse in urban areas are unaware of the service. The centre was piloted at Paropakar Maternity and Women's Hospital back in the fiscal year 2011-12. It was then established in numerous other hospitals after a year or two. Ninety-four different hospitals now run OCMCs across all seven provinces. These centres provide temporary rehabilitation, legal aid, and health services including psycho-social services and rehabilitation free of cost to the survivors.

“When OCMCs were initially set up in hospitals, the only cases that reached the centre were through the police,” said Dr Shrijana Kunwar, head of OCMC Patan Hospital.

“Even today, survivors don’t come to us until it is their last resort,” added Kunwar.

The weight of bringing shame to one’s family, facing discrimination, being stigmatised and socially isolated are other reasons women in urban areas feel compelled to sweep these issues under the carpet.

“The fact that the survivors of domestic violence are still fighting for social acceptance is one of the major reasons behind women hiding their experiences. The way society views them affects how victims feel,” said Manju Gurung, strategic advisor at Pourakhi Nepal, a non-governmental social organisation that advocates for a safer working environment for Nepali women migrant workers (WMWs). “And this social acceptance isn’t something that will cultivate overnight.”

This year’s two “high-profile” cases of sexual abuse, that of Paul Shah and Sandeep Lamichhane, are a testament to how difficult it is for survivors to speak up against their abusers. They were brought to light by the survivors, and a lot of victim blaming followed the cases for several weeks.

“The law is definitely the same for all people but justice-delivery is biased. After all, those responsible for swift justice are all products of this society,” said Uma Tamang, Legal Officer of Maiti Nepal. “Women, not men, are blamed for being sexually harassed and this is one reason women don’t speak up against violence meted out to them.”

Lila, who requested her name be changed for privacy reasons, grew up in a shelter house from the age of six. Even in the supposedly secure premises of the shelter house, she was not safe from sexual violence. Lila, who is now in her early 20s, was sexually abused in her teens by one of the committee members of the organisation. But she didn’t have the courage to speak up against him.

“Everyone talks about speaking up, but what about the consequences? Speaking up against an established organisation working for child protection jeopardises everything for me: my name, my career and all my future plans,” said Lila “The very thought of my abuser paralyses me and the only way out for me from this trauma is psychological counselling.”

Bottling up such a traumatic event can lead to emotional turbulence as well as mental health complications, says Anup Raj Bhandari, clinical psychologist at OCMC Patan Hospital. “Their struggle does not end with speaking up. Their recovery—the process of healing from that trauma takes several months to years. It’s not easy for them.”

Sushmita Regmi, a rape survivor, earlier this year spoke about her experience through a series of TikTok videos. Her revelation forced the police to take action against the perpetrator. Police investigation found Regmi wasn’t the only girl the accused had abused.

Regmi, a minor competing in a beauty pageant, was sexually exploited by Manoj Pandey, one of the pageant organisers. It took her almost seven years to openly talk about the crime committed against her.

“I shared my experiences with my limited friends but I didn’t get the support I was expecting. They instead passed judgement on me,” said Regmi. “Nevertheless, I went ahead and shared my experience online and of course, the response was divided. I chose to focus on the support I got and went after the rapist.”

“It took me seven years to talk about the most traumatic experience of my life,” said Regmi. “If I had more encouragement maybe I would have sought justice sooner and I wouldn’t have had to live with the pain for such a long time.”

Nepali society and the government have a long way to go before victims and survivors of sexual violence can speak up without the fear of ostracisation and judgement.

“The government has been making efforts, but it is still not enough. It is providing OCMC services but hardly anyone knows about it. Access to information and justice is something the government should emphasise more,” said Tamang of Maiti Nepal.

“But more importantly, we all must make concerted efforts to ensure that a woman is safe, at home and outside; that she does not have to live in fear. We have to raise awareness about gender-based violence among men and not just women.”

16.16°C Kathmandu

16.16°C Kathmandu