National

Long fight against culture of rape and impunity

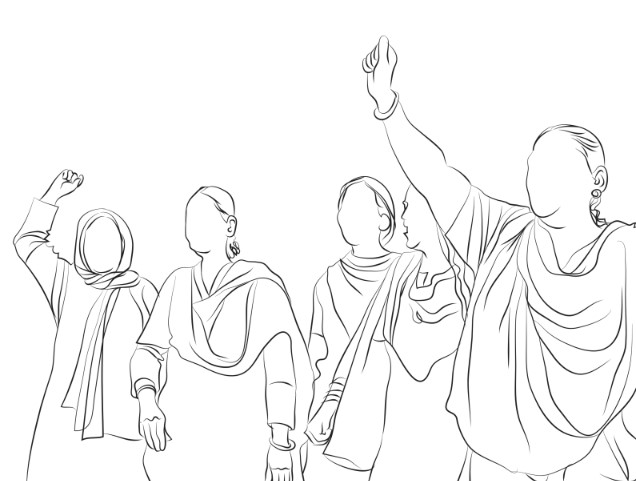

Women know the battle for justice won’t be easily won but refuse to give up. They vow to speak up louder.

Anshrica Dewan

In Nepal, as in the world over, March is celebrated as Women’s History Month wherein women are celebrated for their contributions to history, culture and society at large.

March 8, the International Women’s Day, is a public holiday. In the urban setup, women employees are given the day off, even in private firms that are miserly with their leaves.

However, in the past year, a sense of loss and nagging uncertainty has developed about the future for the womenfolk in Nepal—and many of them are in no mood for celebration this March.

The alacrity with which two controversial rape-accused men were welcomed into the folds of society by an overwhelming majority of Nepalis, both women and men, is a step back in women’s rights reforms, say women rights activists and human rights watchdogs.

Journalist Sangeeta Lama, also a human rights activist, says the display of affection for men accused of raping minors and the hysteric level of support for such men is indicative of a shift in mass opinion. “The division of opinion following the verdicts in the two cases shows an unequal split between the groups that endorse the courts’ decisions and those vehemently against them—with the scales heavily tilted towards the supporters’ camp,” said Lama.

Actor Purna Bikram Shah, better known as Paul Shah, was released from Tanahun prison on February 27 after the Pokhara High Court acquitted him of child sex abuse charges. A 17-year-old singer had filed complaints in February 2022 accusing Shah of raping her in Tanahun and Nawalparasi (East) districts.

The singer accused Shah of raping her with a false promise of marriage. She filed the case in Tanahun days after the controversy arose. She, however, changed her statement later.

On the day of his release, a large crowd of friends, family and fans gathered outside the Tanahun District Prison to greet Shah. His smiling face was splattered across social media platforms and news websites. Photographs of his warm welcome did not make it to the papers the next day solely because they had learnt their lesson from the Sandeep Lamichhane fiasco a few weeks ago.

Lamichhane has been accused of raping a 17-year-old minor on August 21 last year. An investigation is underway against him under Section 219 of the Criminal Code 2074. If the crime against him stands, he will be imprisoned for 10 to 12 years.

Lamichhane was released on bail on January 13 by the Patan High Court. On February 27, the Supreme Court lifted the travel ban on the national cricketer. In a hearing the same day, a division bench of justices Sapana Pradhan Malla and Kumar Chudal ruled in favour of the petition filed by Lamichhane, allowing him to travel abroad.

The rape-accused leg spinner was also embraced by the public, surprisingly primarily women, on his release. The calls for Lamichhane’s release and voices in his support had grown louder as his hearing date neared. When he walked out of the central jail on a cold January day, the same voices poured out onto the streets welcoming the rape accused.

Lamichhane then joined the national cricket team in the United Arab Emirates for the UAE Tri Series of the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup League 2. The team returned on March 7.

“Nepalis, mostly young women and men, came out in support of their ‘heroes’. They rallied to save the men from falling from grace and when the courts decided in their favour, jubilant crowds received them,” said Lama. “However, there is also a section of young women and men, albeit smaller, who have been protesting these decisions. Their voices are not going unheard. Women will come back louder, bolder and with more courage to challenge the prevailing system.”

For survivors of violence, the first and possibly the most difficult challenge is finding the courage to speak up against the abuser. Victims take years to build up the courage to talk about the trauma they faced, even with their close circle.

Reena Moktan, a working journalist currently with Kantipur Daily, the Post’s sister paper, is a vocal woman, who speaks up against injustices. But it took her seven years to talk about the trauma she allegedly faced as a young journalist. In mid-June last year, she finally summoned the courage to call out a fellow journalist who was on his way to leading an association of Nepali film journalists.

“Seeing this man who preyed on young girls climb up the ladder of success while dismissing the accusations I had informally made against him, made me angry,” said Moktan. Even when she made a formal complaint against the man, her protestations were drowned out by the overwhelming support he enjoyed in the Film Journalists Association Nepal, the organisation he would soon lead.

“It was a difficult decision to come out. I had managed to suppress the incident in the dark recess of my mind but when I saw Susmita KC speak up against her perpetrator, Manoj Pandey, I felt brave,” said Moktan. “I decided I should also speak up for other women who may have fallen prey to my abuser's indecent proposals and insinuations.”

In mid-June last year, Moktan, who was a member of the association, through a Facebook post rejected an award that was being conferred upon her by the film journalists association, accusing him of abusing the power he had over a young journalist who had just begun her career.

A barrage of questions followed Moktan’s decision to go public with the accusation: questions from strangers on social media to those from her circle of work friends, with whom she had shared her distress. “A social media trial had begun where I was the one at fault for trusting the man and accompanying him when he offered to drop me home one evening,” she said. “He was given the benefit of the doubt while I was made to stand trial.”

In a blog published on eKantipur.com in mid-June last year, Moktan details her harrowing experience seven years ago. But that did little to help her, she says.

On March 2, the man Moktan had so vocally spoken against for the abuse she faced when she was 20 years old, was elected by the member strength as the association’s president. Following his election, 18 members of the association resigned en masse.

“But nothing changed. The man continues to enjoy his status and even got elected president of an association affiliated with the Federation of Nepalese Journalists,” said Moktan. “That was when I began questioning my decision to speak up. What was the point when there is hardly anyone to listen to you? I feel the Nepali society is unwilling to listen to women survivors, as we also saw in the cases of survivors of Shah’s and Lamichhane’s crimes.”

Jaya Luitel, president and chief executive officer of The Story Kitchen, says the verdicts in cases involving Shah and Lamichhane are a clear sign of how the state and forces that turn the wheels of the justice system in Nepal try to suppress the voices raised by women against injustices.

“In these two cases, the survivors are minors,” said Luitel. “The age factor throws the debate about consensual and non-consensual sex out of the window. If you have any carnal relation with a minor, it is rape. Our law says so.”

Two kinds of justice systems come into play in rape cases. While the formal (legal) justice system plays a very important role in ensuring justice for survivors and victims, the informal justice system governed by unwritten laws, moral values and societal norms plays an equally vital role.

“But in these two cases, the informal justice system had passed its verdict even before the cases reached the court,” she said. “What these cases did was unmask the level of impunity afforded to perpetrators of crime against women. Nepali women see how women’s concerns are easily dismissed even today.”

The prolonged impunity that offending men have enjoyed in Nepal is discouraging, but Luitel strongly believes that rather than being silent and dismayed, women will push back harder and speak up louder.

“Back in the 1980s, three young girls—Namita Bhandari, Sunita Bhandari and Neera Parajuli—were raped and murdered in Pokhara. The only eyewitness to the incident later allegedly died by suicide. It was widely believed that the Panchayat government and even members of the then royal family were responsible. Women came out onto the streets to protest but the culprit(s) never faced legal actions,” said Luitel.

She recalls the decade-long Maoist insurgency in which women fell prey to sexualised wartime violence. Rape and murder of women were widespread but rarely reported or documented. “Today, these injustices and crimes against women are not even spoken about. In recent memory, we have the widely-publicised Nirmala Pant rape-and-murder case. Even now, there have been no arrests. These anecdotes highlight the level of impunity perpetrators of crimes against women enjoy.”

Seeking accountability, Luitel asks for the unmasking of forces protecting these men and giving them the impunity to continue debasing women and their rights. That is what the Nepali public should collectively ask, she says.

.JPG)

That one of the Supreme Court judges presiding over the Lamichanne case was Sapana Pradhan Malla, a woman who had forged her career fighting for women’s rights, had sparked some hope. But when the division bench ruled in favour of the petition filed by the cricketer, allowing him to travel abroad, women felt let down by the system again.

“So who holds the strings to justice? The media should question what or who guarantees impunity to perpetrators of violent crimes against women. It’s definitely not Nepal’s law and policies,” said Luitel.

According to Nepali law, a person below the age of 18 is a minor. The Criminal Code 2017 has the provision of life imprisonment for raping a person younger than 10 years; 18 to 20 years if the victim is between 10 and 14; 12 to 16 years if the victim is aged between 14 and 16; 10 to 14 years if the victim is between 16 and 18; and 10 to 12 years if the victim is older than 18.

Despite disappointing verdicts in the two cases, the incarcerations of Shah and Lamichhane, though brief, suggest the pressure created by individual groups of women and men online and offline carries weight, says journalist Lama.

“Yes, the punishment was not in line with the crimes, but to have Shah jailed for over a year and Lamichhane behind the bars, however briefly, indicates that the corrupt system can buckle under pressure,” said Lama. “It shows the system is aware that there are rights groups, national and international, watching them; that there are people working on the ground for women’s rights. They may expect women to back down and stay quiet but that will not happen.”

Survivors of violence face a two-pronged attack, from the state machinary as well as the members of society who directly or indirectly endorse rape-accused individuals, thereby ostracising the survivors.

When the dust settles on the highly-publicised cases, regardless of the outcomes, the rehabilitation of survivors into society becomes crucial. It determines the quality of life she can expect to lead. At The Story Kitchen, where Luitel provides a safe space for survivors of violence, encouraging them to share their stories, creating an enabling environment is a priority.

“When a woman accuses someone of committing a crime against her, especially rape, the trajectory of her life changes. The mudslinging, victim blaming and character assassination begin the moment she speaks up,” said Luitel. “In cases where the court decides against her, the survivor finds herself more alienated, with more to prove than when she first started. This is when she needs support from her family and her immediate circle. She needs to be surrounded by people who believe in her. Only then can her journey to recovery start.”

The Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2023, published by Informal Sector Service Centre (Insec), in February this year documents 4,228 victims of women’s rights violations in Nepal in 2022. The report documents 605 incidents of rape, 145 cases of attempted rape and 42 incidents of sexual abuse. In 2021, there were only 3,417 such victims in total, up from 2,606 in 2020.

.JPG)

The yearly increase in the cases of violation of women’s rights is alarming, says Dr Kundan Aryal, chairperson of Insec, but also indicates that more and more women are coming forward to report abuse.

“Our data suggest a yearly increase in the violation of women’s rights,” said Aryal. “The figures speak volumes about how women are courageously speaking up, but our study also finds that impunity to offenders is on the rise, which sends a dangerous message about women’s rights in Nepal.”

Political will is vital in determining the fate of any rights movement. In Nepal, the verdicts passed on two high-profile women’s rights violations cases in the past year can be attributed to a lack of it, says Aryal.

“Shah’s and Lamichhane’s cases may have had a different outcome had there been the political will to do the right thing. Nepal has the legal framework and constitutional base to bring the accused to book, so what stopped the legal system from working effectively?” said Aryal. “All three pillars of the state—executive, legislature and judiciary—in Nepal are heavily influenced by politics. This has contributed to the failure of state mechanisms to protect the victims of human rights abuses.”

“Verdicts on Shah and Lamichhane cases are definitely a setback but they also highlight the importance of speaking up,” said Aryal.

Riding on positivity and hope the month of March brings to women all over the world, Surakshya Khadka, a 23-year-old BBA student at Patan College, says celebrating the wins and revisiting the losses give her the strength to carry forward the legacy built by Nepali women in their long struggle for equality and justice.

“Women should never stop speaking up against injustices and we should take this month as an opportunity to band together, lick our wounds and get back up to fight against the likes of Shah and Lamichhane and those who protect them,” Khadka told the Post.

However, for journalist Moktan, celebrations are the last thing on her mind. The fight for truth has exhausted her, she says. “I am still battling to make people listen to survivors and be kind to them. But it’s a long battle that sometimes makes me wonder if Nepal can ever be a country where mothers can hope to bring their daughters up safely.”

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu