Theater

A comical satire on Nepal’s socio-political reality

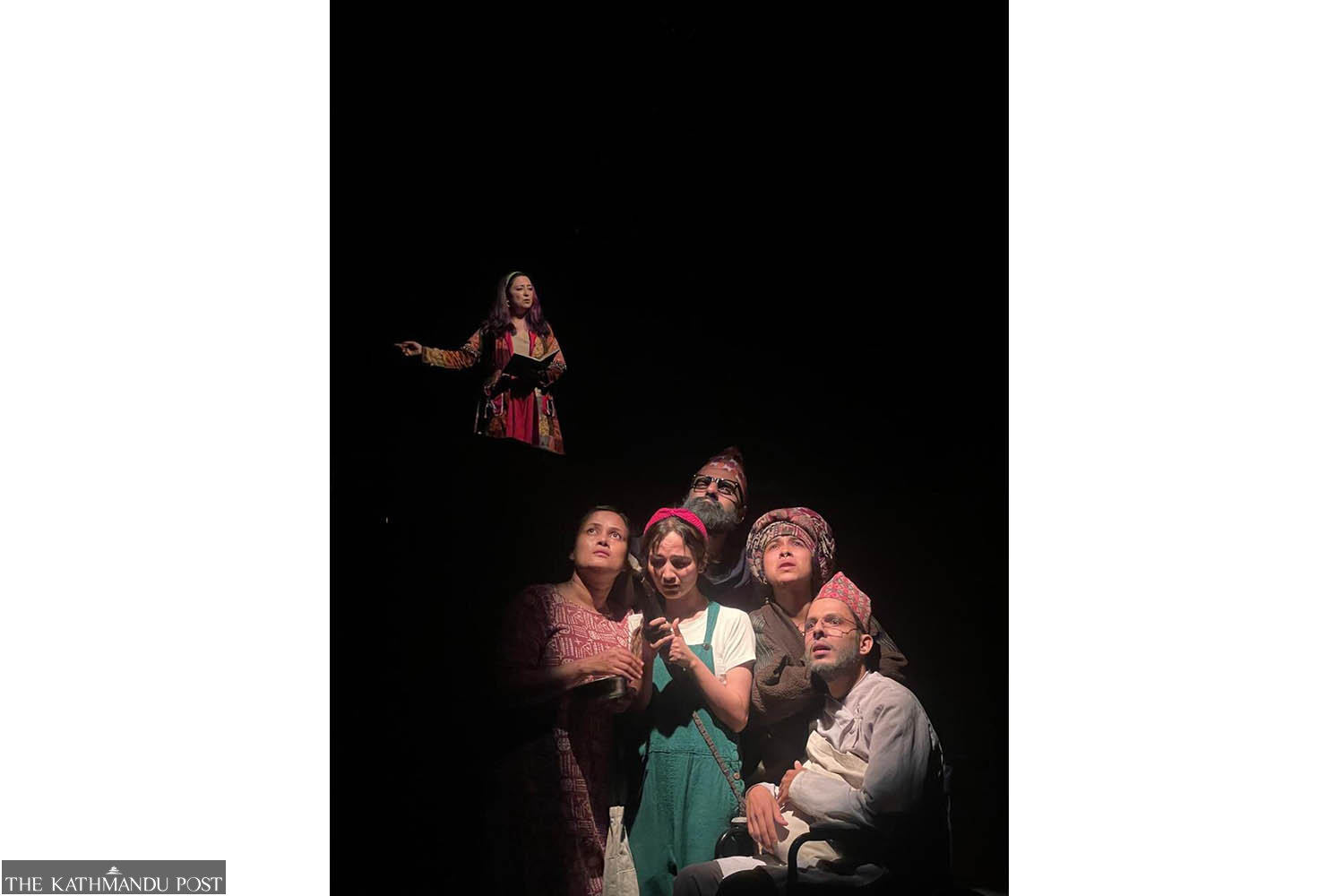

‘Yugko Saancho’, an adaptation of Roald Dahl’s ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’, features five different families, each with their package of antics to be unpacked.

Rishika Dhakal

‘Yugko Saancho’ reflects the turmoil of the many citizens whose lives have been difficult due to dysfunctional government.

The play written and directed by Tanka Chaulagain, is an adaptation of Roald Dahl’s ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’. Instead of Willy Wonka and his chocolate factory, we see Moon, an ambitious textile factory owner.

The story features five different families, each with its package of antics to be unpacked.

Unlike in ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’, where chocolates are more important, ‘Yug ko Saancho’ regards clothes as more essential.

Aabha, the passport seller’s daughter, is the play’s bookend character. With the unabashed spending of her family’s money on new clothes, Abha’s inclination to spend money transpires from her unending dream of obtaining the ‘Yug ko Saancho’ coupon.

‘Yug ko Saancho’, when loosely translated to English ‘Key of the Era’ coupon, is hidden in different purchasable products. Only five lucky customers to find ‘Yug ko Saancho’ will get an opportunity to visit the infamous ‘Moon Industry’.

Moon has created jobs for youths across the country in her industry. Therefore, she is looking for a successor who has the capability to provide tangible and intangible profit to both the industry and the country.

Every little instance in the story has a depth of its own, which symbolises Nepal’s contemporary social landscape.

For instance, all five families of the play embark on a horse race to find the sought-after key, which is similar to the trend of Nepalese people racing to fill out the EDV form for the USA.

Upon finding the coupon, five families are invited by Moon to visit her industry which is stationed in Hetauda. The enigmatic Moon promises a special prize for one lucky winner at the end of the visit to her industry.

The play is characterised by its musical setting, where each character gets their individual spotlight to express their current mental state through musical dance.

Each coupon winner is to be accompanied by a guardian. The characters come from different backgrounds, each with their own temperament and nature.

For instance, the father-daughter duo represents the father-daughter dyad of urban-class families. The father, a typical patriarch, belittles the beliefs of the other people while flaunting his political standing.

His daughter, on the other hand, is a bubbly little girl whose privileges have blessed her with the ability to refrain from rudeness toward others.

Similarly, the mother-son duo symbolise the typical modern-day relationship of a mother with her son and vice versa. The son, with his carefree Gen Z attitude, never fails to make the audience erupt with laughter.

The mother-daughter duo, a typecast depiction of the so-called “social media influencers,” depicts the lifestyle of a self-proclaimed trendsetter.

The duo’s portrayal in the play is the director’s slam to the many who chase after superficial fame.

Likewise, Ankur, the fourth character, is a businessman. He is represented as an innocent young man, yet the nuances of his character are filled by the depth he provides through his enthusiastic approach to learning about the machines of the Moon industry, which irritates other characters.

From my observation, Ankur’s eagerness and enthusiasm to learn about machines portray the energetic youths of the country who want to start businesses of their own.

The annoyance and exasperation that he faces from other characters represent the state’s failure to supply youths with the required resources to start their own businesses in the country.

As the play progresses, Moon gives the lucky winners a tour of her factory. The tour features the turn-wise downfall of each character due to their own actions.

Some get eaten by the machine, whereas some get turned into a pumpkin.

The play places a special emphasis on Karma, echoing the fatalistic maxim embraced by Nepali society: fate is determined by one’s daily actions.

As a family-friendly play, it has incorporated moral lessons for its young audience. Through the characters’ unfortunate fates, the director warns the young audience to be disciplined and cautions them against harbouring excessive ambition.

Analogously, Ankur’s fall while examining the machines imparts the moral lesson that it is difficult to get out of an addiction once it has taken hold.

“Udhyog garne kasailai aafaile jalaaunu naparos,” when roughly translated to English, states that the businessman may never have to burn themselves alive.

This phrase captures the incident in Nepal where a year ago, an entrepreneur, Prem Prasad Acharya, self-immolated in front of the federal parliament building.

Moon, a leader of a business factory, sets an example that business can be run by women. This can be contrasted with the prevalent paradoxical structure of the government, where the Ministry of Women is headed by a man.

The play’s major objective and strength is depicting the grim realities of the nation. It has also attempted to debunk various notions circulating the Nepalese diaspora, such as the perception of politics as merely a “dirty game”.

In a similar vein, the characters begin to vent their frustration towards Sharmaji, the father of the father-daughter duo, pointing out that every party’s manifesto contains ambitious and far-fetched promises that do not necessarily cater to the pressing needs of the citizens.

As his fate stands, Sharmaji gets caught up in the industry’s machine and is later eaten by termites. The rendering of such scenes is intended to make Sharmaji taste the bitter medicine of his own making.

This particular scene can be compared to the sufferings faced by farmers who fall prey to the exploitation of middlemen (bichauliyas).

In a country where reusing already-worn clothes is a Sisyphean task, the play, with its admixture of lessons, introduces the concept of thrift.

It has tried to deconstruct the shame surrounding wearing thrift clothing.

Similarly, Moon’s other objective is to flourish the country’s industrial landscape by exporting clothes made in Nepal.

In her unrelenting effort to make her winners understand the importance of wearing locally made clothes, she comes up with the idea; “If Nepali clothes were also worn in schools, how beneficial would that be?”

In hindsight, the play is ‘less talking and more doing’. As a result, the cast is all dressed in clothes made in Nepal, emphasising the fact that one doesn’t need to hunt Chanel or Gucci to showcase style and elegance.

In the end, the winner of the special prize is bestowed with the responsibility of running Moon’s industry.

Moon’s expectations from the winner are woven into the melodious melody sung by the music team.

The lyrics urge people to make the best use of Kirtipur’s handicrafts, Lalitpur’s statues, and Ilam’s tea leaves.

The play concludes with the lesson that stopping mass emigration and encouraging the return of those who have strayed abroad are crucial for the country’s development.

Self-reliance is now the key to the door of the upcoming era.

Yug ko Saacho

Director: Tanka Chaulagain

Cast: Akanchha Karki, Sebita Adhikari, Sheela Niraula, Rara Jyoti Pokhrel

Duration: 1 hour 30 minutes

Venue: Shilpee Theatre, Battisputali, Kathmandu

Showtimes: Every day at 5:30 pm and an extra 1:00 pm show on Saturday until August 3

18.35°C Kathmandu

18.35°C Kathmandu