Visual Stories

Chasing the ‘lahure’ dream

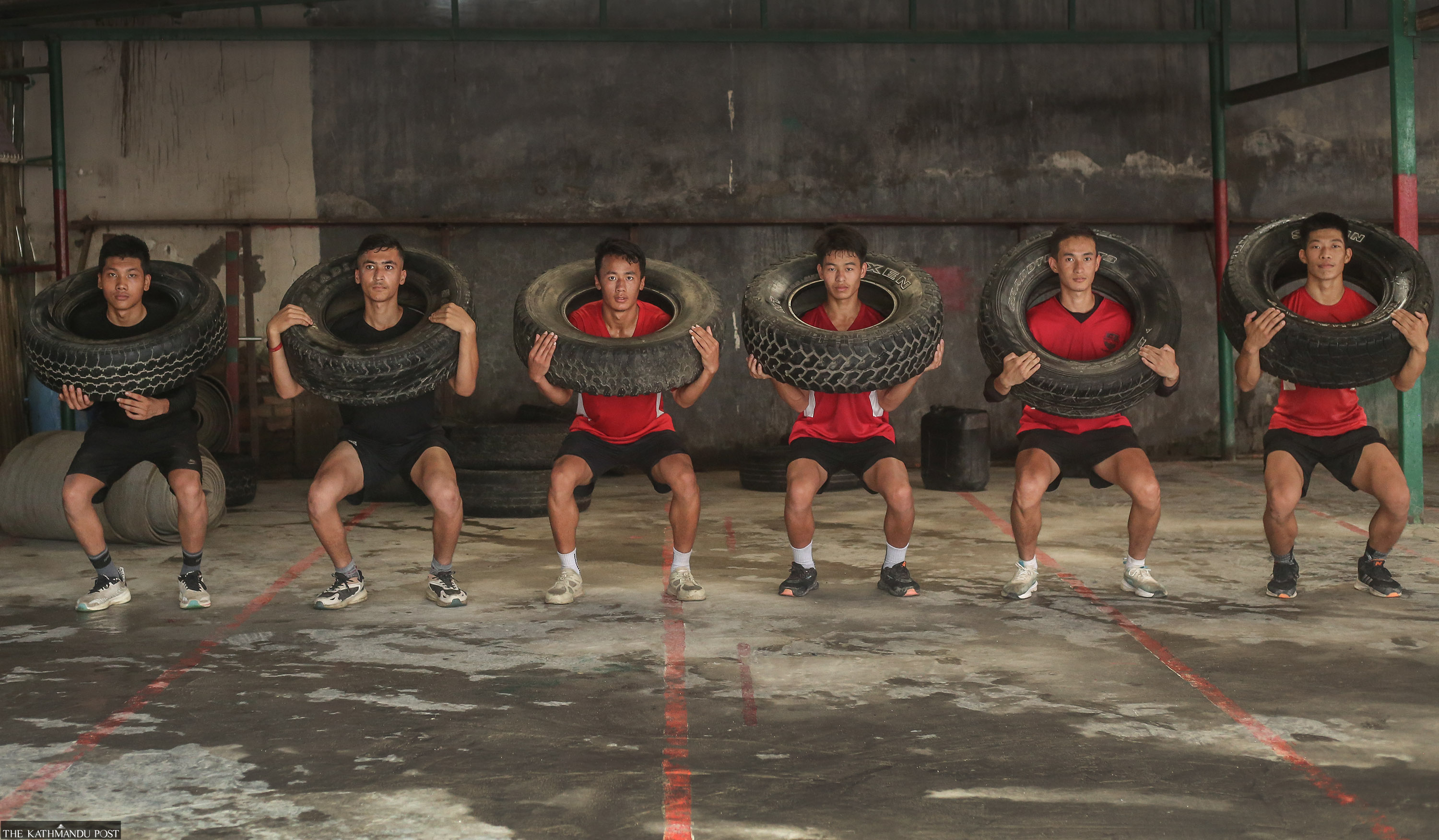

Every morning, dozens of young men gather at the ‘Bright Gurkha Training Center’ in Koteshwar to get into either the British army or Singapore police.

Prakash Chandra Timilsena

Nineteen-year-old Bikram Tamang wakes up every day at five in the morning. He washes up and puts on his running shoes. As the soft rays of the morning sun fall upon the still and quiet of the Valley, he steps out of his house and does some warm-up exercises. Except for women rushing to nearby temples with fresh flowers and half-awaken students slopping away to morning classes, the streets are mostly empty. Savouring in this momentary silence in a city that thrives in its eclectic chaos, Bikram begins running.

From Imadol in Lalitpur, he runs all the way to the ‘Bright Gurkha Training Center in Koteshwar.’ All the while, one single image continuously plays in his mind—getting into the Singapore police and becoming a ‘lahure’. Originally from Majhuwagadi municipality in Diktel, Khotang, he has been living in Kathmandu for four years and training with ‘Bright Gurkha’ for one year. He had also tried to enrol in the Singapore police last year, but his application was sent back due to faulty paperwork. But this time, Bikram isn’t going to let anything stop him. His paperwork is up to mark, and he has already passed the first round. Only the second and third rounds are left. He is leaving for Pokhara on Saturday, where the second selection round will take place on September 3.

Every morning, dozens of young men like Bikram Tamang make their way to ‘Bright Gurkha’ Training Center’ to train. The centre, nestled between residential houses in Koteshwar, features a large tin roof under which the students practise everything—from running and jumping jacks to pull-ups. Motivational posters are plastered along the cornermost wall, hoping students find something to look up to when things get tough.

These boys, many of whom have just finished high school, abandon the allure of being young and brash—alchohol, parties and fast food, and follow a strict dietary and exercise regimen to make their cut into foreign military institutions in countries like Singapore and the UK.

But things are rarely easy. To survive in the Capital—which is rarely generous regarding food, rent and expenses—Bikram took up odd jobs to earn money. Before joining ‘Bright Gurkha,’ he used to work as a delivery boy at a painting shop—where he often worked from nine in the morning to seven at night. “I barely had any time to exercise or prepare for the Singapore police, so I ended up quitting the job,” he says.

Despite hardships, his dream of becoming a ‘lahure’ is still strong. “Back home, people used to look at me and say, ‘he has a physique of a lahure’ and that created an impression on me,” he says. Moreover, Bikram reveals he is also enamoured by the prestige his uncle—a Singaporean police official—gets in his home town.

However, the Nepal army or even the Indian army aren’t on his radar. “I have never considered those as my options,” he says.

The term ‘lahure’ has a long history in Nepal’s emigration. Even before the East India Company (EIC) began recruiting Nepali soldiers, the term ‘lahure’ was initially reserved for those who went to Lahore (now a city in modern-day Pakistan) to enrol in the armies of states to the west of Nepal. The EIC—allegedly impressed by the bravery and loyalty shown by Nepali soldiers—began recruiting them into their military after the end of Nepal-Anglo war. After that, the term ‘lahure’ eventually lost its grandeur to ‘Gurkha.’ However, the word ‘lahure’ still holds significant colloquial power—as it denotes any person who works as a part of a foreign military.

Makar Tamang, a 20-year-old from Diktel, also reaches ‘Bright Gurkha’ at six in the morning. He wakes up at four and takes a public bus from Bhaktapur to Koteshwar. After finishing his +2 (twelfth grade), he dropped out of college to entirely focus on training for the Singaporean police. Makar, who comes from a family of 13 members, is the youngest among four siblings.

“There were many ‘lahures’ in my village—the respect and the service facilities they received attracted me,” he says. When asked why he doesn’t wish to try his luck in the Nepali army, he says, “I respect the work being done by the army, but the money and facilities given here aren’t enough to support a family.”

The dream of becoming a ‘lahure,’ thus boils down to the very reason why thousands of young Nepali individuals flock to foreign countries—the hope for better jobs and, subsequently, a better life.

In the last four years, the quota allocated for Nepalis in the British army has been reduced by more than half from 432. Earlier, in 2022, 218 were recruited by the British and 140 by Singapore. For 2023, despite thousands of men applying, only 196 men will be selected for the British army and 140 for the Singapore police.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu.jpg)