Columns

Reflecting on the past years

Our political class should feel ashamed for having let down the Nepali people for so long.

Mohna Ansari

Coinciding with the end of my six years on the National Human Rights Commission, it is good to have some time to reflect on the achievements and challenges of those years. Among the many positive and critical aspects, two things stand apart.

Firstly, the harsh reality that five years into our new constitution, caste and gender-based discrimination is as pervasive as ever. So is the discrimination against the poor and vulnerable. It almost seems like Nepal is determined to hang on to all the diverse ways of discrimination it has practised over the centuries. Discrimination over citizenship seems to be the most discussed element of the new constitution. There has been no relief for excluded communities even after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2006 promised to end all forms of discrimination—caste, ethnicity, religion, region, gender, sexual orientation. All those destined for the dustbin of history in 2006 are still alive and kicking in 2020.

What will we tell them?

Ending any form of discrimination takes a long time, and legislation is only one part of the story. Still, it is disappointing to see that there are not even any signs of an emerging momentum for implementing Nepal’s promises. I wonder how this will play out when Nepal has its next Universal Periodic Review at the UN in Geneva, where all nations are invited to give an account of their progress on upholding rights over the previous four years.

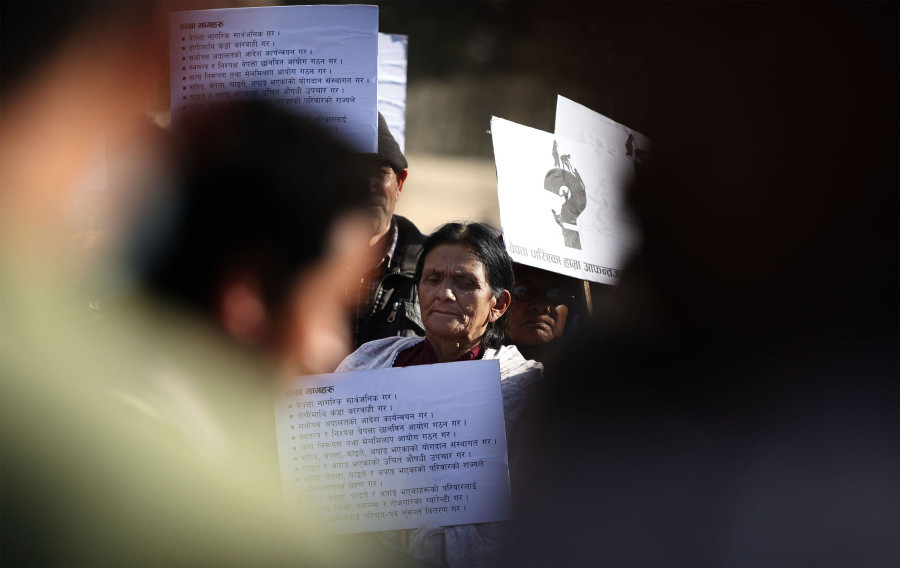

The other thing that jumps out at me is the plight of the victims of the conflict. Fourteen years after the CPA promised them truth, justice, reparations and reforms to prevent repetition, the victims still have nothing more than the empty words of the government.

This was brought home to me again this week with the publication by Advocacy Forum and Human Rights Watch of No Law, No Justice, No State for Victims, a new report on the state of transitional justice since 2006, an X-ray of our rule of law. This is, in fact, a sad portrait of a nation stuck in injustice, where justice being denied is routine. Unfortunately, we have become a country that is unable to learn the lessons of a decade of disastrous conflict.

It is a well-researched report, but it is also depressing. Obviously, the main focus is on how successive governments since 2006 have failed to deliver on their promises on justice. If I had to pick one of them, it is the commitment to clarify the whereabouts of the more than 3,000 or so ‘disappeared’ Nepalis wrenched from their homes and families, never to be seen again. The families are denied justice while the signatories to the CPA had committed to revealing their fate within 60 days. To be precise, what happened to all these innocent people was to be made clear before the monsoon of 2007. We are ending 2020, and no progress has been made so far. No proper compensation has been provided to the relatives of the disappeared who were left behind, except bits of ‘interim relief’ given in a tokenistic manner.

The same is true about the commitments to proper transitional justice more generally. It took our political class eight years just to set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Six years have passed since then with no further progress. All this doesn’t look accidental. In 2015, the Supreme Court ordered the government to amend the act creating the Transitional Justice Commission to bring it in line with our constitution and international standards. No progress has been made so far. The report should make our political class feel a little ashamed for having let down the Nepali people so much for so long, for failing to give us justice and a police system we deserve as a basic right.

The problem with the lockdown is that perhaps it has given us a bit too much time for introspection, as I have also been thinking about what this says about the National Human Rights Commission, human rights non-governmental organisations, victims’ groups and civil society in general. Could we not have done more to bring about a satisfactory closure to transitional justice? I think that if we had found a bit more unity around some basic common demands, we could have had more impact.

Why was unity so elusive when the needs were so common to us all? Why could we not set aside personal and party interests to fight for the common good—an end to impunity? No one is safe. Not during the war, and not now, 14 years later. It might be the primary responsibility of the various governments, but was there really nothing more that civil society could have done? Remember, we still claim that it was civil society that ended the war, and brought the republic and democracy. Yet the processes that led to this peace are left incomplete.

Take a good look

Nepal’s international friends, too, should take a look at the impact of all their funding on access to justice and other programmes around transitional justice. Is there anything that they can learn from the experience of the past 14 years? I think that, in particular, they should review how they fund civil society groups. Some feel that there is a tendency, unintended, to create an unhealthy competition between the groups looking for funds. Supporting transitional justice is not easy. It is a delicate issue and there is resistance from groups who see their interest in maintaining the status quo. But transparency is essential if trust is to be built. An honest self-critique of the impact so far cannot be avoided if progress is to be made.

It is time to assess coldly and take stock of what we have done with the peace that cost us so much. It is time to see if we can do better from now on. It is hoped that, in another 14 years, this article will seem like the arguments of a distant past. Nepal and Nepalis should not continue to make the same old mistakes. Let’s try and make the regrets mentioned here irrelevant—as soon as possible.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu