Columns

Dismal narratives of education

Education is more necessary for those who obstruct and politicise it.

Abhi Subedi

The dismal narratives of higher education in particular and the education system in general that regularly come out these days make me pensive. The main contention of the news is that the Nepali political parties and their organisations that cover the domains of education, culture and arts are harming the system by politicising education and its functionality. News of political intervention in the smooth process of education and the related practice of obscurantism are quite disturbing. This subject is discussed in responsible media outlets, in the meetings of enlightened minds and in the parliament. Politicians and government leaders bandying about politics and education is particularly worrying. One hears gross negligence of the subtlety that the culture and practice of education cover. First, I want to put the nature of some news and views on this subject.

The common themes of the narratives are that the culture of education and its practice are suffering. Imageries of death and funeral for educational karma are used in some articles. The stories of political appointments to fill up some regular educational posts at the university find great publicity. The agencies of this contentious subject mainly come from the two major ruling parties, the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist). The impression I get from reading some news is that this subject, which could be handled easily with prudence, discussion and common sense, is getting out of control. Narratives of physical attacks, fulminations and vengeance are rife.

This story of the NC-UML binary in education creates doubt about the honesty and pragmatism in education propagated by political parties. The general public has even begun to question the seriousness of political alliances in bringing a state of order, standard and decency to the educational system.

Politicising education through party interference is already established as a hegemonic practice in Nepal. When the Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci used the term hegemony, he had in mind a practice or a state of consciousness that is accepted as a norm across society. And the point is that it becomes pragmatically easier to handle a situation and people by means of that tacit consensus.

Division of political nature among the stakeholders, educational administrators, students and political parties that have long adopted the partisan culture for their organisations has created hegemony. The Nepali educational system, especially at the tertiary level, clearly shows this.

The other side of reality

I have spent most of my life working in the field of pedagogy, research and related engagements at the tertiary level. People like me and those with similar experiences have worked under different conditions of politics and transformations, hopes and obscurantism. I am still working, if not regularly, as a teacher and supervisor of students’ research work. I attend the students' forums and present my views on theories and cultural studies. Some students are doing their PhD under my tutelage. I have a long experience working with students both at and outside the Kirtipur campus.

A certain enduring sense of being a teacher under different conditions of inspiration and pragmatism still guides my sense of working in education. Being a politically conscious person and one who worked with political ideologies even as a student in the past, I do not want to sound naïve in politics and education. I am familiar with the works and plans of students who espouse various ideological camps summed up by such nomenclature as the Nepali Congress, UML, Maoists and even the erstwhile Panchayat system.

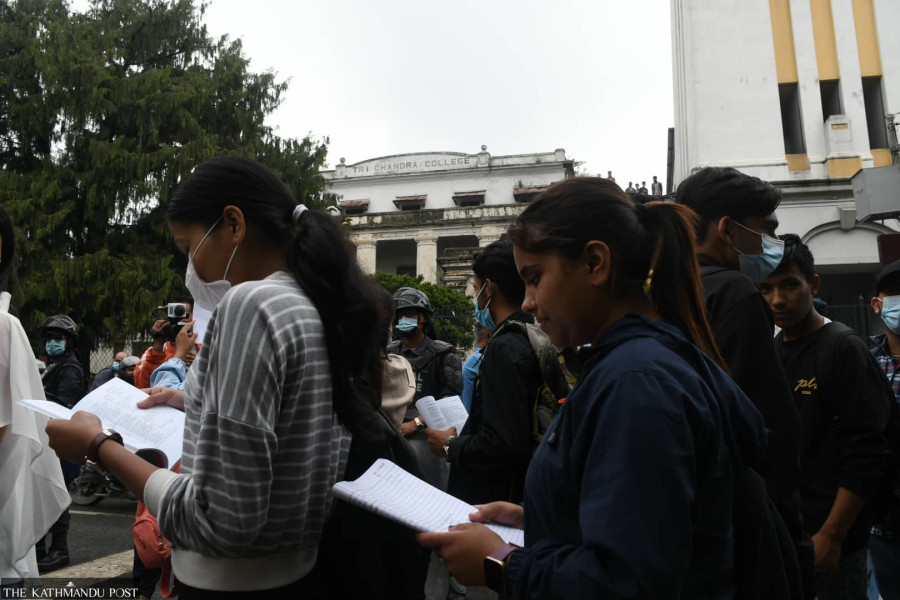

To take one recent and eloquent example, I was watching the news of the launch of a book named Nakabandi ra Bhurajniti, written by my former student Kamal Thapa, with Prime Minister KP Oli as the chief guest the other day. Kamal has penned his experience representing and defending Nepal's new republican constitution at a meeting in Geneva while working as Nepal's foreign minister. He had not even fully accepted the constitution then. I do not agree with Kamal's political ideas, but this example suggests that students' political engagements and teachers' free relationships do not necessarily end with their ideological followings. I have a long experience of this nature. This requires a more extended discussion with theories and experience. As a teacher, I can say that students' political interests and associations are natural. The claims that students have destroyed the education system by their different views are hard to accept. As the news and commentaries criticise, they have not dragged education to a point of no return. We should also see this side of reality: Students write good dissertations, research papers, essays and rhetorical texts; they read books and magazines in print and online. What is harming education is the following.

Sometimes, political parties and their leaders encourage students and teachers to espouse a culture that sows the seed of hatred. The other side is a reckless process of filling the university posts and positions on party lines rather than based on merits. It is dismaying that some teachers give credence and encouragement to this culture for perks, positions and parties. Barbaric events of physical assaults show the culmination of the reckless use of politics and partisan culture in education. However, I have recently read that the university authorities are taking measures to promote fairness and transparency in educational management.

Hard times

We are working in the most challenging times for two reasons. First, political parties and their leaders are debating a subject that needs a careful and thoughtful assessment. It is not tenable to say that since teachers and students have made great contributions to politics, their engagement and activism in education are justified. This reflects the arrogance of those leaders and parties and their tendency to integrate party activities within education.

The second challenge is the need for prudence, vision and urgency to bring reforms to the existing education system, which is dogged by various problems, including non-educational self-interest. The practice of pedagogy and the culture of research and opening to new realms of knowledge are functioning. Serious teachers, students and researchers are engaged in this. Let us not promote a culture of cynicism and mistrust. Doing so would be running away from responsibilities. In reality, education is more necessary for those who obstruct and politicise it.

9.88°C Kathmandu

9.88°C Kathmandu