Columns

Ambedkarism with a Nepali flavour

Hindu religious reformation is a must, as conversion doesn’t necessarily liberate Dalits.

Mitra Pariyar

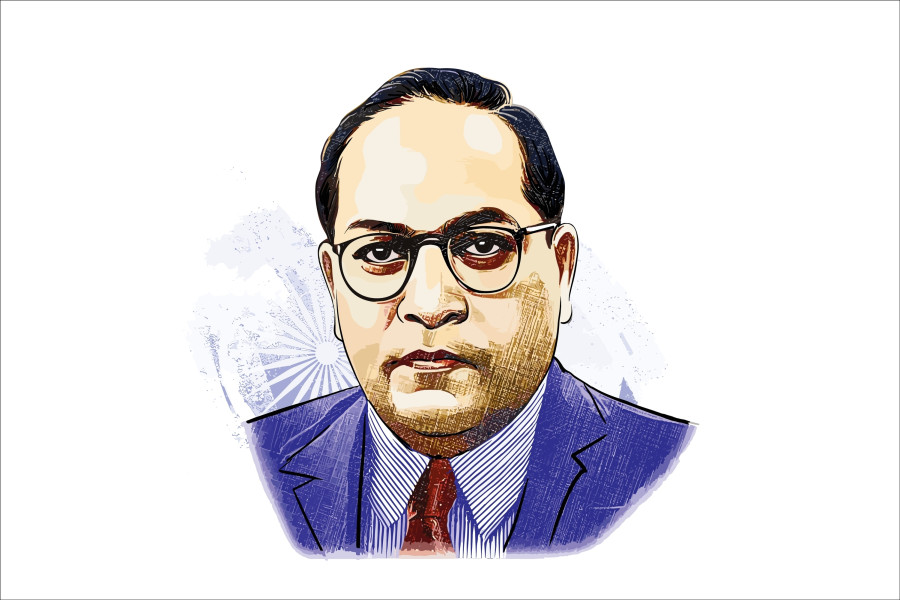

Ambedkar Jayanti is marked on April 14 to celebrate the birth of the great Indian politician, philosopher and social reformer Dr BR Ambedkar. He was born in the year 1891. Ambedkar is probably the only historical figure of South Asia whose popularity has increased over time. I argue that Ambedkarite ideology is the last hope of Nepali Dalits.

His life and deeds, including his radical theorisation of the Dalit freedom struggle and his mass conversion to Navayana Buddhism in 1956 as a pathway to freedom from caste, still fascinate many scholars, activists and ordinary people.

In 2024, noted Indian Dalit activist and scholar Dr Anand Teltumde published a book entitled Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, where he suggests shifting from the great man’s hagiography and critically re-examining his ideology and politics in the face of the persistent plight of Dalits. I agree with Teltumde’s advice. Here, I examine the relevance of Ambedkarism in today’s Nepali Dalit freedom struggle, albeit with a caveat.

Ambedkar who?

Few Nepalis have heard of Dr Ambedkar. We rarely read his biography and debate his ideology. I also hadn’t heard of his great work until I went to do my Master of Philosophy (MPhil) in anthropology at Oxford University towards the end of 2008.

The main reason for the neglect of Ambedkar in Nepal is the preponderance of communist and/or socialist parties. For some reason, communists in both India and Nepal, including the leftist Dalit intelligentsia, have developed a strong dislike for him. Dalit writer Aahuti openly labels Ambedkar as a failure!

Ambedkar did, however, study and analyse Marxism. He delivered a remarkable speech, entitled Buddha and Marx, at the fourth World Fellowship of Buddhists in Kathmandu on November 20, 1956, which has been published and continues to be read and analysed to this day.

This speech, amongst his other works, enables one to understand that Ambedkar wasn’t entirely antagonistic to communist or socialist ideology. American-Indian scholar Dr Gail Omvedt testifies to this fact. Ambedkar had two major objections regarding Marxist thought: Advocacy of dictatorship or autocracy (in the name of the proletariat) and the use of violence.

Ambedkar was also a fierce critique of Brahmanism. In several of his writings and speeches, he stated that the communist USSR had done a good job of exporting the Marxist theory to India but made a blunder by handing it over to the Brahmins, who, in his view, can never be genuine communists.

I agree with this perception. As in India, nearly all communist or Marxist parties in Nepal are led by upper-caste Bahuns. These left-wing leaders preach that religion is the opium of the people, but don’t give up their sacred thread!

Relevance in Nepal

Contemporary Nepali Dalit politics badly needs a critical review or a paradigm shift. It has become largely defunct and ineffectual at the moment. I suggest that Ambedkarite ideology is the only untried and untested ideology that could revive our freedom movement and deliver results.

A majority of our Dalit politicians, activists and intellectuals consider themselves Marxist or socialist. Some are more orthodox than others. Yet a majority of Dalits are attached to parties calling themselves communists. And, like their political masters, they haven’t been able to give up Hindu religion and culture.

As a consequence, Dalit rights defenders themselves actively practise social hierarchy and untouchability. They are both the victims and victimisers. Inter-Dalit discrimination is widespread, but there’s hardly any discussion on the issue.

Internal hierarchy is reflected in the fact that, for example, nearly all the leaders of the Dalit wings of the political parties are the Bishwakarma. This caste occupies the top rank amongst hill Dalits.

I’d like to explain the gravity of the situation further using a recent incident in the Siraha district. A Dom family was forcibly displaced because a grand religious event was planned at the site and their presence was deemed polluting.

There was an outcry when the incident surfaced in the media. The perpetrators, including the ward chairman from the People’s Socialist Party, were detained for a few days for practising untouchability so publicly.

Looking deeper, however, the legal action against the dominant Yadavs hardly changed anything. Because other castes, including Dalits like the Paswan, Chamar and Musahar also keep the Dom—considered the lowest of the low—outside their social circles, especially from their religious functions.

Dalits also practise discrimination in their own homes. They treat their menstruating women and girls as untouchables and keep them separate, especially from sacred sites, for a certain period. Likewise, Dalits treat their people observing funerals as untouchables. They practise untouchability during the birth of a child as well. And do not let people from outside the lineage, including married daughters and sisters, participate in the worship of their kul devta.

Herein lies the major contradiction in the Dalit freedom struggle: How can we rid society of untouchability when Dalit leaders and activists themselves practise it so widely? If we want to clean up society, we must keep ourselves clean first.

Ambedkarite ideology can show us a way out of this mess. Dalits will be enlightened when they read or listen to his thoughts (such as the famous The Annihilation of Caste, 1936; Riddles in Hinduism, 2008). They will then understand how the Hindu religion and culture have been the actual sources of caste hatred.

Conversion vs reformation

Following Professor Teltumde (2024), I’d suggest that we must not accept Ambedkarite ideology uncritically. We must use it according to our socio-political environment. Today’s Nepal is certainly different from the India of the 20th century.

Unlike many followers of Ambedkar, I don’t think Dalits converting to Buddhism would liberate them. Ambedkar turned to Buddhism because, as Omvedt and others have noted, he saw it as an atheistic religion. He loved the morality at the centre of Buddhist practice, instead of a deity.

Now this is only true for some sects of Buddhism, such as Theravada. Unfortunately, there aren’t many followers of Theravada Buddhism in Nepal. The Vajrayana and Mahayana Buddhist sects popular in Nepal are full of supernatural forces and superstitious beliefs. Overall, the Hindu caste order has made its way into the Buddhist world as well.

As in India, Nepali Buddhists, Muslims, Kirantis and even Christian converts haven’t been immune from caste hierarchy. Therefore, unlike Ambedkar, I would recommend Hindu religious reformation for social transformation instead of conversion. The fact that Dalits suffer greatly in southern India, where Christians have existed in significant numbers for hundreds of years, shows that conversion doesn’t necessarily liberate Dalits.

17.8°C Kathmandu

17.8°C Kathmandu