Health

Nepal’s 30 districts at high risk of cholera outbreak

Epidemiology and Disease Control Division working on a cholera elimination plan. Mass vaccination under consideration.

Post Report

At least 30 districts, including all three districts of Kathmandu Valley—Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur—are highly vulnerable to cholera outbreaks, public health officials said, citing poor water and sanitation conditions in those areas.

These districts often witness outbreaks of diarrheal ailments during the monsoon and have been designated as high-risk districts for cholera outbreaks, according to officials at the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division.

“We are still working to locate cholera hotspots based on risk mapping,” said Dr Yadu Chandra Ghimire, director at the division. “We are also preparing a cholera elimination plan and identifying measures required to implement it.”

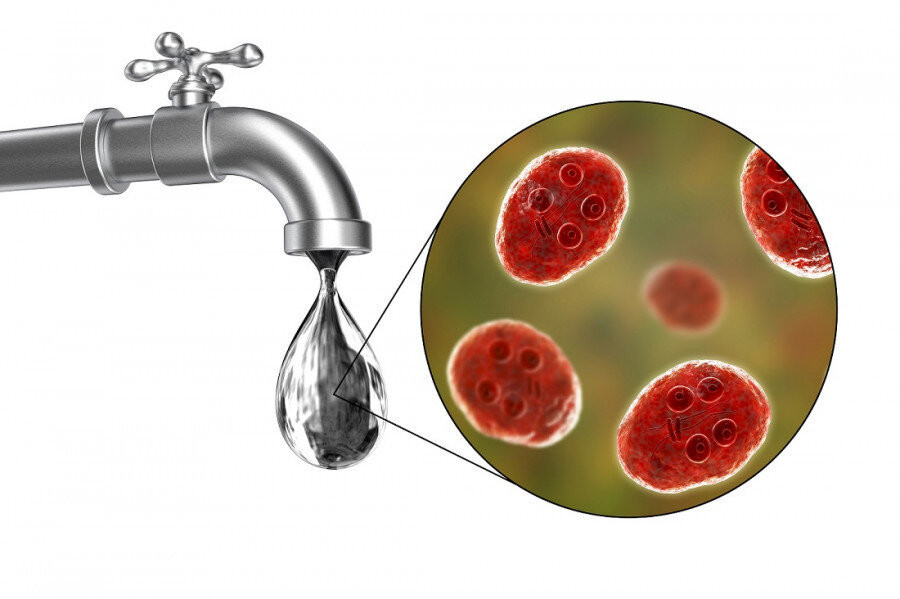

Cholera is a highly infectious disease that causes severe diarrhoea and vomiting, leading to dehydration and even death within a few hours if left untreated. Cholera outbreaks are not new to Nepal, as they are recorded every year, especially in the monsoon season.

Nepal witnessed a massive cholera outbreak during this year’s monsoon. At least 95 cases of cholera infection were confirmed in Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Kailali, Pyuthan, Makawanpur, Rolpa, Sindhupalchok, Achham and Rautahat districts.

Health officials said that the Vibrio cholera 01 Ogawa serotype was found in the stool samples of the infected patients. Hundreds of people suffered from the diarrheal infection that continued for months.

In 2022, too, the Kathmandu Valley witnessed a massive cholera outbreak with at least 77 confirmed cases. Officials said that the outbreaks were reported in districts that have active case surveillance programmes. Active cholera surveillance is being carried out from 27 health facilities in the Valley and 10 in the Kailali district.

“We are also working to declare sentinel surveillance sites, at least one in each province, for active surveillance of cholera,” said Ghimire. “Discussions are underway to launch mass vaccination campaigns in high-risk districts.”

Officials said that the cholera elimination plan needs to be approved by the Department of Health Services and the Ministry of Health and Population. If both agencies agree that vaccination is the most effective way to halt cholera outbreaks, the agencies concerned can approach aid agencies for vaccine doses.

Health authorities had administered oral cholera vaccine in wards 11, 12 and 13 of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, which were severely affected by the disease outbreak in May last year.

Public health experts say that the risk of waterborne diseases, including cholera, will not lessen until and unless the country's water and sanitation conditions improve, and people are ensured safe drinking water. Several other factors, including the condition of supply pipes, water storage, and pollution in water sources, impact the quality of water supplied to households.

“Mass cholera vaccination is only a short-term solution,” said Dr Shyam Raj Upreti, former director general at the Department of Health Services. “Our focus should be on improving water and sanitation conditions.”

Due to poor sanitation and hygiene conditions, Nepal is highly vulnerable to water-borne diseases, including diarrhoea, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis, and cholera, with thousands of people falling sick every year.

Health officials said the cholera elimination plan focuses on improving water, sanitation, and hygiene programmes, with support from development partners, including the World Health Organisation, Unicef, and other agencies.

A study carried out by the Health Ministry following an outbreak last year showed that nearly 70 percent of drinking water samples in Kathmandu Valley were contaminated with E coli and faecal coliform.

Doctors say the only ways to save people from dying from water-borne diseases, including cholera, are to launch awareness drives and ensure safe drinking water. According to them, a combination of surveillance, water, sanitation and hygiene, social mobilisation, and treatment is required to contain the spread of the infection.

The World Health Organisation says cholera is a global threat to public health, and a multifaceted approach is key to controlling the disease and reducing deaths.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu