National

She eloped when she was 16. Now she’s serving time for child marriage

The law on child marriage is so vague, it often ends up criminalising victims rather than perpetrators.

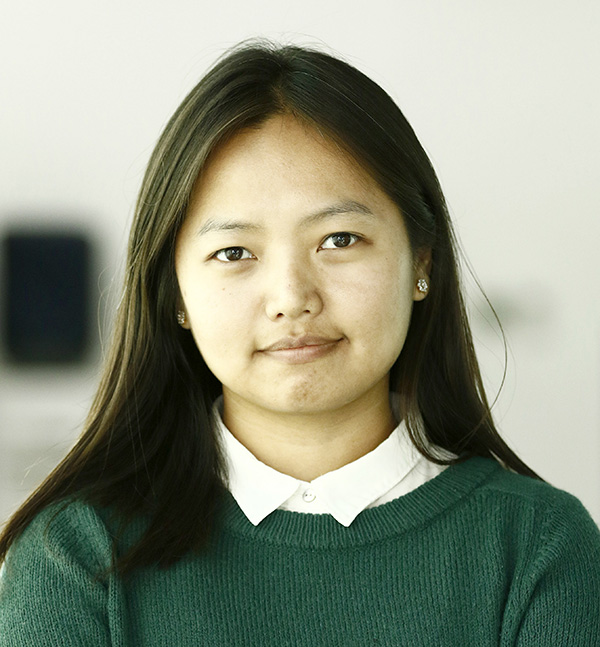

Tsering D Gurung

In February last year, Poonam, an eleventh grader from Bajhang, eloped with a boy she had met on Facebook. She was 16. He was 18.

Poonam had barely begun to settle into her new home when she was visited by police personnel who informed her that a complaint had been filed against her and her husband, Raju, for child marriage and polygamy.

Unbeknownst to her, Raju, whom she had known for less than a month, was already married. His first wife, who had been living with her parents, had gone to the police after finding out he had taken a second wife.

Although Poonam and Raju were never customarily nor legally married, their living together at his parent’s home was considered proof of their union. Neighbours testified that the two were cohabiting and that in the police’s eyes constituted marriage, said officials at the correctional home who had knowledge about the case. Both Poonam and Raju’s names have been changed upon their request to protect their privacy.

Poonam, now 17, is serving time at a children’s correctional home in Bhaktapur after she was handed an eight-month sentence by the Bajhang District Court. She is also eight-months pregnant. Meanwhile, her husband, who was sentenced for 20 months, is on the run.

“I had no idea he was married,” Poonam told the Post. “Neither did I know that our relationship was illegal.”

Child marriage has been illegal in Nepal since 1963. Two years ago, the government increased the legal age for marriage from 18 to 20. As per Article 173 of the Criminal Code, a person found guilty of either committing or arranging a child marriage is subject to a jail term of up to three years and a fine of Rs 30,000. However, in many cases, these legal provisions, aimed at protecting children from child marriage, have ended up being used to penalise them instead.

“How can you punish someone who is not capable of making informed decisions,” said Sagar Bhandari, a programme officer at CWIN-Nepal, an organisation that advocates for children’s rights. “The law is supposed to protect victims of child marriage, not punish them.”

Bhandari, who is also a lawyer, said the problem lies in vaguely defined provisions related to child marriage, which do not make a clear distinction between who is a victim and who is the perpetrator.

“The current provision on child marriage has only three lines, one of which states that those who marry and those who arrange such a marriage will be held liable,” he said. “It’s just very vague.”

Nepal has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world. Nearly 40 percent of women in the country get married before turning 18. The number of child grooms is also high, with one in every 10 men getting married before 18, according to the 2016 National Demographic Health Survey.

But only a few dozen cases get reported to the police each year. In the last five years, the police received less than 150 complaints related to child marriage. In contrast, over 5,500 rape cases were reported during the same time period.

“Nepali society still does not view child marriage as a crime,” said Lachhindra Maharjan, programme manager at Save the Children. “It’s still very much accepted as a cultural norm and therefore, people rarely come forward to report cases of child marriage even though it’s happening all across the country.”

Among those that do get reported, the majority are filed by parents in situations where the children have eloped against their wishes, according to officials at the correctional home. But if marriages are arranged by the families themselves, people hesitate to file complaints.

“The community usually turns a blind eye to child marriage because people think it’s a personal matter,” said Anish Poudyal, a social worker, at the correctional home. “It is only when there is a person or a family aggrieved by the union that cases get reported.”

Even in Poonam’s case, had her husband not been married previously, the authorities would most probably not have been notified.

“What’s ironic is that a child marriage case should have been filed against the first wife, who was 23 at the time of marriage with the boy, who was only 15,” said Jyoti Shrestha, a counsellor, referring to Poonam’s case. “But because both families had agreed to the marriage, no one reported it.”

Recently, another young couple ended up spending 11 months at the correctional home after their families filed a child marriage case against them. The two belonged to different castes and had eloped.

Initially, the boy’s family had welcomed the girl into their home. But the girl’s family, who were unhappy about the relationship, filed a case against the boy because he belonged to a so-called lower caste. In retaliation, the boy’s family then filed a complaint against the girl.

“More than genuinely reporting child marriage, the law has become something of a tool to settle personal scores,” said Bhandari.

While in these two cases, children ended up serving nearly a year at a correctional home, in other cases involving adults, the court has often let the perpetrators off with lenient sentencing.

For instance, in the case of Nepal v. Kaluman Rai, the father of a 13-year-old girl who confessed to having arranged the marriage of his minor daughter, the court sentenced him to only three days of imprisonment and a fine of just Rs 25. In another case, CWC Surkhet v. Govinda Sunuwar, which involved the marriage of a 13-year-old girl to an adult, the perpetrator was punished with three months’ imprisonment and Rs 1,000 fine.

While traditionally, child marriages were arranged by families, an increasing number of under-age couples run away together. More than 30 percent of child marriages happening today are by elopement, according to a survey conducted by the Nepal chapter of Girls Not Brides, a global network campaigning to end child marriage. The survey was conducted in five districts with a high prevalence of child marriage.

“You have to look at what’s driving child marriage,” said Anand Tamang of Girls Not Brides-Nepal. “Once we get to the bottom of that, then we can get to solutions.”

Children rights activists say that among the several factors pushing young couples towards eloping, stigma surrounding premarital sex ranks high.

“A lot of these young couples are forced to run away because Nepali society, in large part, does not have a dating culture,” said Sumnima Tuladhar, executive director at CWIN-Nepal. “Premarital sex is a big no-no and for teenagers who are beginning to get sexually active, there is often no other way than to run away and live together.”

One measure, activists propose, is to introduce lessons on child marriage and sex education in school curriculum.

“We need to start talking about sex openly so we can normalise it,” said Tuladhar.

A key thing to remember is to not view the problem of child marriage in isolation, said Maharjan of Save the Children.

“It’s linked to a lot of different issues: poverty, education, gender disparity,” he said. “Unless we take those into account, punitive measures won’t work.”

Nepal aims to end child marriage by 2030 as part of its commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In 2016, the government endorsed a national strategy that provides an overarching framework to end child marriage. Among the six pillars listed in the strategy is strengthening and implementing laws and policies. This is particularly important, given problematic provisions.

Presently, the statute of limitations on reporting child marriage is three months, which is insufficient, lawyers say. Additionally, such marriages can be declared void only after an individual reaches 20. And even then, if the woman has had a child from the union, that right is taken away.

“The Ministry [of Women, Children and Senior Citizens] should seriously look into the current laws and amend them accordingly if it’s genuinely committed to ending child marriage,” said Bhandari.

For Poonam, who is due to deliver next month, her situation is not extraordinary. Most of her friends back home in Bajhang are married and some already have children of their own.

The only difference is that someone reported her to the authorities.

“They’re living their lives,” said Poonam. “And I am here.”

22.65°C Kathmandu

22.65°C Kathmandu