National

World Cup comes to Kathmandu

People in the Valley already knew of football in 1930.

Prawash Gautam

After practice, Raju Manandhar, a footballer with the then A-Division team United Youth Club, and his teammates headed to Makhan, where they had arranged for a television owner to show them 1986 FIFA World Cup matches aired by Nepal Television (NTV).

In his article ‘Taking a Trip Down Memory Lane: 1986’, 55-year-old Manandhar captures the atmosphere of a World Cup-gripped Kathmandu.

“We swarmed into one room long before the live matches on the TV,” he writes. “The friends from other localities also would join the gathering nothing short of a small carnival. The whole locality would be echoed around with the noises supporting their favorite teams [sic].”

For Manandhar, who began playing football as a schoolboy, the 1986 and 1990 editions of FIFA World Cup helped cement his love for the game. This was also true for his teammates, friends, and most of Kathmandu.

Missing and reading World Cups

The inaugural World Cup was hosted by Uruguay in 1930. It has been held every four years since (except in 1942 and 1946, during the Second World War).

Football was already known to Kathmandu in 1930. By 1934, matches were organised between local football clubs in the Rana durbars and Tundikhel amid much fanfare. The state-owned newspaper, Gorkhapatra, Nepal’s only daily at the time, started covering local football matches as early as the 1930s. The league games, Tribhuvan Challenge Shield, began in 1947. In 1952, ANFA was formed.

However, little is known if the World Cup’s early editions were known to Kathmandu. These early World Cups are missing from pages of Gorkhapatra, a rare window into the outside world to the “forbidden Kingdom”, even though it was already publishing international news, including Hitler’s rise in Germany and the tense build-up to the Second World War in the 1930s.

Shyam KC played for Kathmandu’s famous Sankata Club. Aged 19 during the 1958 World Cup, he doesn’t recall knowing about that World Cup. Like him, Komal Bahadur Pandey, 81, another noted footballer of his time, also does not remember learning about the World Cup until much later.

As teenage footballers in the 1950s, KC and Pandey would most likely be interested in World Cups. Their ignorance about the games in this decade suggests that the World Cup became known to Kathmandu much later.

“It was most possibly in the 1960s that I heard about the World Cup,” said 83-year-old KC.

“1966 World Cup was when Kathmandu’s residents started taking special interest in these games,” said Pandey, who started playing for the Mahabir Club in 1953 and led Nepal’s team to the Agha Khan Gold Cup in East Pakistan in 1963.

Both KC and Pandey swiped through the pages of Indian newspapers and magazines for World Cup news in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Indian newspapers gave good coverage to sports news. They had photographs as well,” said KC, who became a daily buyer of Indian newspapers The Statesman (Calcutta edition), The Hindustan Times, The Indian Express, The Times of India, and Navbharat Times in the 1960s.

In the 1960s, The Rising Nepal, Gorkhapatra’s sister publication that started in 1965, also began covering World Cups. “The 1966 World Football Cup begins,” reads the newspaper’s headline on its July 13, 1966 issue after the event kicked off in London. After no or negligible coverage of the 1970 and 1974 editions, sporadic coverage was back in 1978. But the two national-level newspapers left football enthusiasts dissatisfied even until the 1982 World Cup.

“Football is the most popular game in Nepal,” wrote a disappointed Indrachowk local JP Rauniyar in the July 2, 1982 in a Letter to The Rising Nepal titled ‘Football Fever’. “The massive media coverage of the games is reflected in the prominence given to it in the live telecasts, radio commentaries, and other international magazines. The Rising Nepal, however, seems to be an exception. Why?”

Such irregular coverage is attributed, according to the editorial note in The Rising Nepal, to the “poor reception of the news from AFP […] has adversely affected our coverage of […] the World Cup.”

For a Kathmandu that was beginning to take an interest in the World Cup through newspapers and magazines, a section of the city had a rare moment after England won the trophy in 1966.

According to Pandey, the British Council gave him three-hour-long World Cup reels and tasked him with organising shows in different localities.

“One reel contained the final match between England and West Germany,” he said. “Two others contained highlights from other rounds. I organised shows in various localities in Dillibazar, Gyaneshwor, Ratnapark, Bagbazar, Bijaya Memorial School, Sano Gaucharan and other localities interested in football.”

Listening to World Cup

Radio was one of the most common sources of World Cup news even until the 1980s. When NTV decided to telecast 1986 matches, certain locals were concerned that results on radio would dampen their excitement.

“I would like to suggest that the matches be telecast at about seven in the morning the following day,” wrote one Sudhir Sigdel to The Rising Nepal on June 3, 1986. “[I]t would also help make it rather ‘fresh’ to the viewers. If it is telecast in the evening it might be ‘stale’ since the viewers know, by this time, the results of the matches from the radio.”

“I listened to the running commentary of the World Cup on the radio. Due to time zone differences, the commentaries mostly aired at night in Nepal, but I always felt energised to listen to All India Radio, BBC World News, Voice of America and other radio stations,” said KC of the World Cup in the 1970s.

Manandhar’s elder brothers also listened to radio commentaries of the 1982 World Cup.

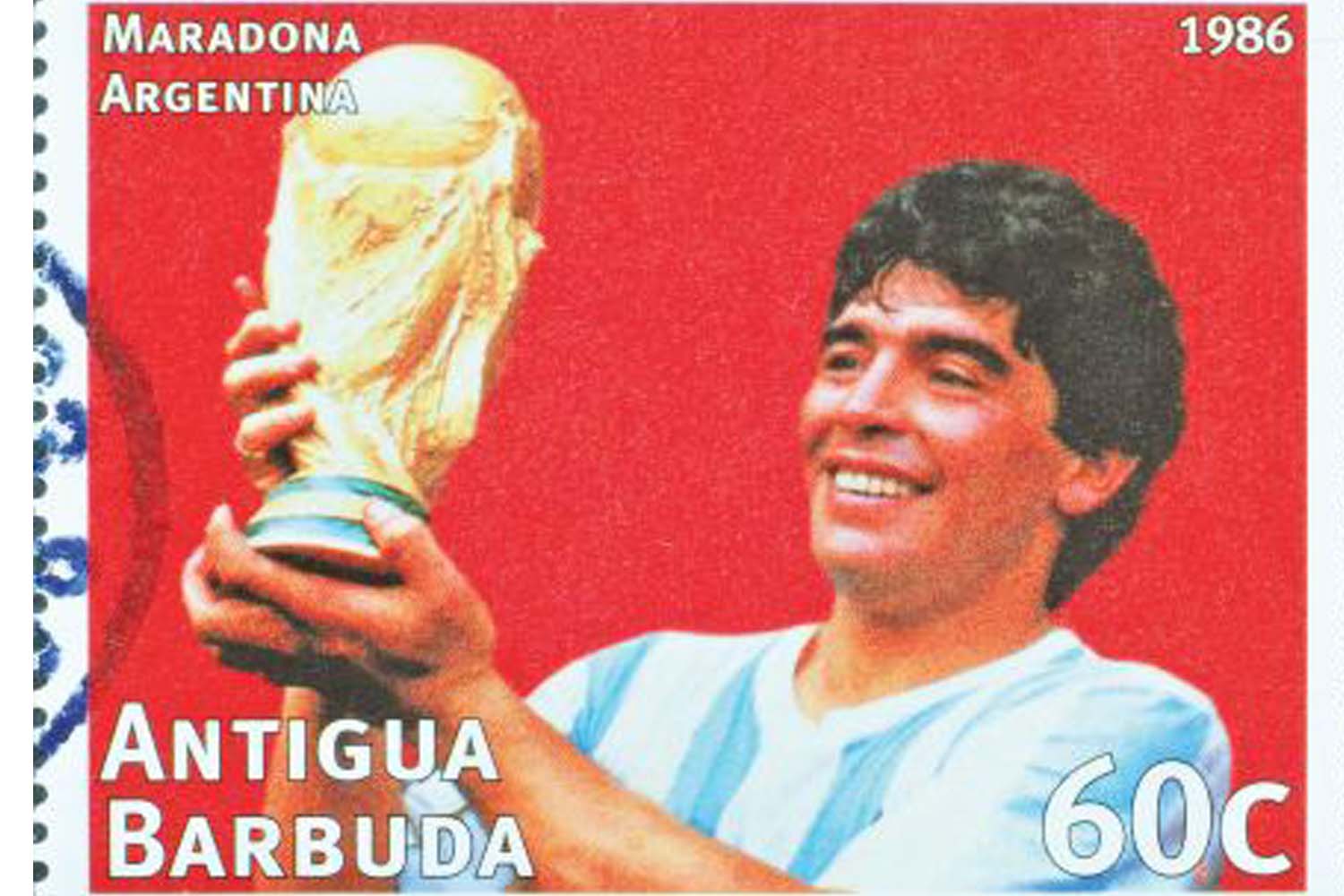

“Radio commentaries created an atmosphere for the 1986 World Cup as they were the most popular means of learning about international football and stars,” said Manandhar. “We heard a lot about [Diego] Maradona on the BBC in the years preceding the 1986 World Cup.”

NTV blossoms World Cup to life

With supplements and editorials dedicated to the World Cup, Gorkhapatra and The Rising Nepal’s coverage of the 1986 and 1990 games show increased interest towards the tournament, a development that also owed partly to KC becoming The Rising Nepal’s chief editor in 1985. But crowds gathering around television sets to watch the NTV telecast of the matches is what defined these two World Cups.

In 1985, NTV was founded under the leadership of actor and director Nir Shah.

“Football was hugely popular in Nepal, and NTV decided to cash in on it,” he said. “We got the necessary rights from Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union, recorded the matches from a Latin American channel at our station in Balambu and broadcast them.”

The World Cup broadcast received such a rapturous audience that it soared NTV’s popularity, said Shah.

“Official figures stated that Nepal had only around 200 television sets then,” he said. “But I believe the figure was some 350-400, with around 200 sets in Kathmandu and others in border areas like Birgunj.”

Since television was still a rare commodity, crowds magnetically convened in front of televisions all over Kathmandu to watch the matches.

While Shah watched the games at the NTV studio, he recalled that hundreds of neighbours crowded in front of the Sharp colour TV he had brought home while returning after completing filmmaking studies in the UK in 1985.

Reminiscing the gatherings at the Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk, where he was a student, Koirala said, “The hall wasn’t enough to accommodate the crowd of students, so they spilt over to the doors and corridor outside and around the windows.”

In 1990, NTV aired the matches live. Television’s impact on Kathmandu’s World Cup experience—and vice versa—is evident from TV sellers taking on the golden opportunity to push their sales, as shown by their advertisements on Gorkhapatra.

Pele’s legend, Maradona’s magic

Pele and Maradona, two great players of their generations, represented two different eras of Kathmandu’s World Cup experiences.

“I watched Pele’s matches in those reels so many times that I lost count,” Pandey said. “I watched them if I couldn’t sleep. I watched them before heading to Dasharath Stadium for every Mahabir match. Seeing Pele play filled me with romance and energised me for the matches.”

“I still vividly remember Pele ambling on the shoulders of two persons after being injured by a Portuguese player in 1966,” Pandey added.

Unlike Pandey, who got the rare chance to watch Pele on video, most Kathmandu locals pieced together the star in their imagination through newspapers, magazines, radio news and commentaries and word of mouth in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Although I didn’t see him play, even listening to commentaries was something I found fulfilling,” said KC, who heard Pele play through commentaries in the 1960s. “Pele became my idol.”

The Pele that Kathmandu came to know was blended with myth and legend.

“We heard that in the 1962 World Cup, Pele defied his devastating leg injury to score goals and lead his country to triumph,” Manandhar said. “But it was only later that we learnt that Pele had missed the 1962 World Cup after the injury.”

Pele also became loved for his interaction with an Indian footballer of Nepali origin, Shyam Thapa. In 1977, Pele played a friendly with Thapa’s Mohun Bagan in Calcutta.

“In school, we would hear that Pele patted Thapa on the back and remarked that he had good potential. We felt proud about this,” said Drona Koirala, 61, originally from Jhapa. “Pele was not only the greatest player but also one sentimentally attached to Nepalis. That’s how we felt.”

Unlike Pele, Kathmandu saw Maradona’s magic on television.

It was the 55th minute of the quarter-final between Argentina and England in the 1986 World Cup. Maradona dribbled the ball forward past several players, and covering half of the field in 11 seconds and 11 touches, he scored the goal that has been celebrated as the goal of the century.

“It was a large crowd and all Argentina fans,” said Manandhar of the crowd that gathered to watch the match at Makhan. “We erupted in celebration as Maradona scored the goal.”

In his article, Manandhar reflects on Maradona’s grip on Nepalis. “Nepalese had a God-sent opportunity to watch […] global superstar play live on TV. All were extremely thankful to NTV,” he writes. “They were overwhelmed to see the superhuman performance of Maradona in all seven matches he played and the greatest individual goal in WC history.”

In 1990, Kathmandu watched West Germany captain Lothar Matthaus lift the trophy after beating Argentina in the final. But what was etched on the viewers’ memories was the image of Maradona weeping like a boy at his loss.

World Cup is here to stay

By the end of the 1990 World Cup, television and Maradona had set the tone for Kathmandu’s experience of future World Cups.

“Eh Meena, Argentina, harera gayo, Maradona” [Oh Meena, Argentina, Maradona left defeated] or its variation “Eh Meena, Argentina, royera gayo, Maradona” [Oh Meena, Argentina, Maradona left crying] sang the children, testifying that watching the World Cup and Maradona on television was irreversibly transfixed in Nepal’s psyche.

Already in 1986, Manandhar saw Kathmandu locals rallying around various teams. “For the first time in Nepal, football fans rallied around their favourite teams in an organised way,” he writes. “Mostly, flags of Italy, West Germany, Brazil, The Netherlands, France, Spain, Argentina, etc., were seen dangling from the houses, mainly in downtown Kathmandu.”

The 1990s saw the rise in television culture and the mass consumption of global television channels that further popularised football and the game’s stars. The 2000s saw the growth of the internet and the era of mobile phones. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Gautam is an independent researcher with an interest in social history.

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu