National

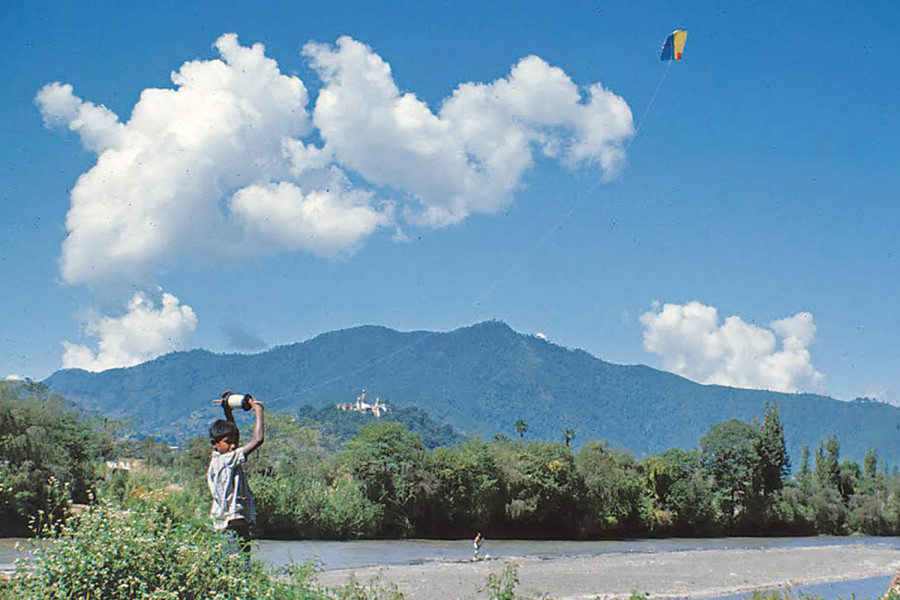

Kites over Kathmandu sky

Clear blue sky and gentle westerlies signal the arrival of kite flying season.

Prawash Gautam

Chaaaiiittt…

The spontaneous eruption of the sound of victory thundered through the neighbourhood of Nhyokha in the Kathmandu core. The line of a kite cut another.

Looking out the window of her house, Sajani Shrestha saw children running full speed, shouting and fighting as they vied to catch the falling kite and thread. And craning her neck up to the sky, she could not count but only be mesmerised by the innumerable kites strewn across the skies of Nhyokha, Bangemudha, Indrachowk.

“There would be so many kites that they entirely covered the blue of the sky, making beautiful patterns of different colours,” says the 51-year-old. “And you cannot imagine the number of times the call of chait rang in the air.”

Clear blue sky and gentle westerlies, the season of kites has arrived in the Kathmandu Valley. While kites soared Kathmandu's sky mainly during Dashain, the kite season officially started in Nag Panchami (August) and ended on the Haribodhini Ekadashi (November). And from royalities to commoners, young and old all flew kites from rooftops and open grounds. Even those who did not, like Sajani, revelled in the live spectacle in the sky as kites soared and fought.

With Bhimsen Thapa’s help, King Girvanyuddha flies kites

The earliest written account of kite flying is believed to date to 200 BC in China. In Kathmandu, this tradition has religious and socio-cultural and environmental significance, says Tina Manandhar, lecturer of Nepalese History, Culture and Archaeology at Tribhuvan University. According to her, it is believed that kites in Kathmandu skies carry a message to the god of rain Indra that the valley's farmers have had enough rain for their crops. That is why Kathmandu farmers scolded anyone flying kites before plantation season.

In an article ‘Changako Utpati Ra Bikas’ published in Gorkhapatra in 1995, historian Rajesh Gautam points to the lack of written documents indicating the exact time when kite culture was introduced in Nepal. Exploring different opinions on kite's introduction to Nepal, he writes that “some have opined the possibility that the skill and tradition of kite flying might have entered Nepal through India.” Yet some others, he writes, state that kites “came to Nepal from Japan during the time of [Rana PM] Dev Shumsher.”

He concludes that most likely this tradition was introduced by Malla-era Newar traders: “But since Nepal’s relationship with Tibet and China is very old and direct, kites might have entered Nepal through the Newar traders who were engaged in the trade. One can estimate that the kite was introduced to Nepal during the (mediaeval) Malla regime.”

In Social History of Nepal, TR Vaidya, Tri Ratna Manandhar and Shankar Lal Joshi write that there exists documented evidence of the kite flying from the early 19th century. The authors state that Sundarananda, a contemporary poet, has mentioned that the young king Girvanyuddha Bikram Shah (r.1799-1816), with the help of Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa, flew kites from the towering temple of Taleju Bhawani, Hanumandhoka. And when the king's kite cut the kites of the youngsters, they were located and rewarded with money.

In Tyas Bakhatko Nepal, Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pandey states that “During the month of Kartik [October-November] young and old all flew kites,” suggesting that kite culture was ubiquitous in Kathmandu by the early twentieth century.

Anticipations and preparations

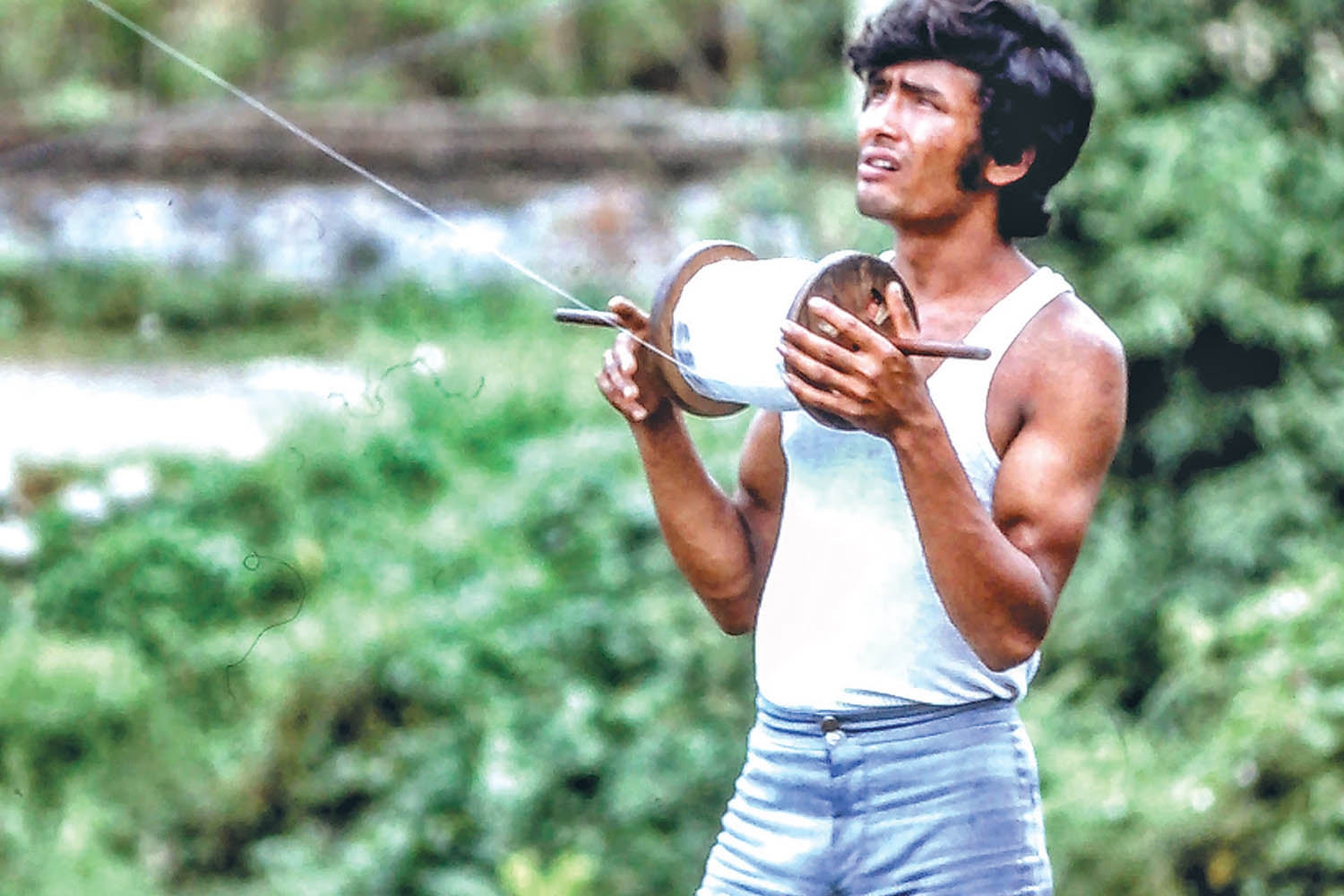

Kite flying in Nepal requires a kite, a lattai (a wooden spool), thread and majha (homemade adhesive prepared by boiling snail slime, rice or sago, and powdered glass from burnt electric bulbs and coated on the line to sharpen it for kite fighting).

77-year-old Nirmal Man Tuladhar, an avid kite flyer and retired professor of Linguistics at the Tribhuvan University, explains how Nepali tradition of kite flying was both expensive and needing advance preparation.

“In our times, it wasn’t easy to fly kites,” he says. “We had to prepare majha …And as Nepali kites are fighter kites, we mainly fought with other kites [which meant we spent a lot of threads].”

This preparation needed first and foremost of passing a hurdle: securing finances and materials to fly kites. While lattai was a one-time investment that could be saved for years, kites and threads had to be replenished every time a kite was cut.

“Those were the times when parents wanted us to be more focused in our studies. They only gave money [to buy kites] after immense pestering,” says 80-year-old Dwarika Nath Dhungel, former Secretary of Nepal government, speaking of the 1950s and 1960s.

Biodiversity specialist and botanist Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha, 86, was born in Mahabouddha and began flying kites from 1951-52. He saved what little money he got for afternoon snacks to buy Hattimar reel, a brand of line wound in a small lattai, which was strong and sharp and where majha stuck well.

Raghuji Pant, a member of parliament, also recalls the difficulty in securing money to sustain his kite flying in and around Kathmandu core in the 1960s and early 1970s. “Four to five of my kites were cut in a day,” writes the 67-year-old in his 2019 article “Changa Jastai Udi Hidne Man” published in Himalkhabar. “[This caused] the line in the spool to shorten. From Bhadra [August-September] to one to one and a half months after Dashain I spent flying kites. So, it was difficult for me to have enough kites even after getting money from grandfather, grandmother, mother and everyone.”

Kites and thread secured, now began the crucial work of preparing and applying majha whose strength determined how well it cut other kites. Govinda Tandon, 70, a historian and heritage expert, who grew up in Battisputali, was also an ardent kite flyer.

“Materials for making majha were prepared right from the morning on a holiday," he writes in his article “Dashainko Butte Changa” published in Gorkhapatra. “Because this work couldn’t be accomplished without a collaboration of 3-4 friends, a holiday was set aside for this. Moreover, a sunny day was considered appropriate. If the majha didn’t dry, the thread could turn moist, and so if it felt like the day wouldn’t be sunny, the entire plan…was aborted.”

Kite makers, kite sellers and variety of kites

One of the oldest shops in Kathmandu's memory, Shree Chitrakar Kite Center in Tyauda, Asan is bustling with customers during Dashain. “When my grandmother got married and came to this house at age 12 [in early 1940s], this shop was already here,” says its fourth generation owner 47-year-old Dinoj Chitrakar. “So the shop must be around a hundred years old.”

Another shop that stands out in Kathmandu's memory is Manandhar Kite Center in Kalimati, established in 1949, and currently run by brothers Mohan Man and Sundar Man Manandhar.

In his book Antar Taranga, artist and writer Manuj Babu Mishra recalls “a kite shop near the old halwai shop of Chabahil” in the 1940s. Dhungel and his 1960 batchmates of Juddhodaya Public School recall the kite shops from the 1950s and 1960s – Bekhacha’s Shop at Netapacho, Bhaicha’s Shop at Nhyokha, Lata Manandhar’s Shop at Maru, Kanchha Buddha Bajracharya Shop at Tyauda.

Besides the shops, there were makers and sellers of kites cloistered in different localities of Kathmandu Valley.

In Kwalkhu, Patan was a Joshi who made Nepali paper kites.

“One day I accompanied my uncle to buy kites," writes Dibya Giri, 69, in his 2023 article “Changa” in Sahitya Post. “I was amazed to see the huge stacks of kites there. We used to call it the house of the kite maker.”

In Nhyokha, Purna Bahadur Shrestha began making kites as a teenager and started his own kite business in the 1950s, according to his daughter Sajani.

These kites, made out of Nepali paper, often had different paintings. Mishra recalls painting kites for the kite shop in Chabahil.

“I went to that kite shop and with the freely available colours and Nepali papers, I spent my day painting faces, birds, animals, masks, mountains, hills, whatever came to my mind,” he writes in the book. “Such kites apparently sold well!”

Most septuagenarians and older generations like Tuladhar and Tirtha Bahadur recall flying kites made of Nepali paper when young. Tirtha Bahadur says that kites from Lucknow began coming to Kathmandu only after the late 1950s. But at least a section of Kathmandu was flying kites from Lucknow from the early twentieth century. Vaidya, Manandhar and Joshi write that the Ranas and Shahs imported kites from Lucknow and that from them, their favourite employees also got to fly some. These kites were large and, in Tyas Bakhatko Nepal, Pande writes that they were referred to as Lucknowia kites.

Known for their characteristic hissing sound they made while flying, light body, swift movement and ability to take sharp turns, Lucknow kites were preferred by kite fighters.

“Lucknow kites were lighter and could be manoeuvred well,” says Tuladhar. “Kites of Nepali paper were stable but difficult to manoeuvre. They were also expensive. So only some fighters flew Nepali paper kites.”

The kites had different names depending upon their designs and colours – Ambe (a heart in the centre), Dibdibe (chequered), Pakhete (a different coloured paper on one edge), Sete (white-coloured), Nilchi (blue-coloured), Rate (red-coloured) and so on.

The kite fighters preferred the strong and sharp Hattimar reel that came on a small lattai. The Belchamar reel was cheaper but weaker and prone to be cut by other threads.

Kite fliers and kite watchers on rooftops and open grounds

Bibek Shrestha, 57, and his two brothers took stacks of kites and climbed their rooftops. The rooftops around theirs in the neighbourhood of Nhyokha – in fact in all core settlements of the Valley – were filled with kite fliers and spectators. Many risked precariously balancing on the sloped roofs.

While Bibek and his brothers’ kites alighted to meet the sea of kites in the sky, their sister Sajani and other family members gathered around to revel in the live spectacle.

Dhungel remembers the rooftops of Jhochhen and surroundings of the 1950s and 1960s swelled with kite fliers. Dhungel did try to fly kites. But he did not become a successful kite flyer. What he did become was, like Sajani and many Kathmandu residents, an admirer of kites soaring in the sky.

“But more than engaging in my unsuccessful kite flying attempts, I enjoyed looking at the kites flying. There would be a big crowd of spectators. Females and other family members watched the kites fly as they ate meat and chiura. Some even drank and rejoiced as they flew kites.”

When the age of cassette player and speakers dawned in the 1980s, songs blared from the speakers alongside kite flying. Chitrakar and Bibek invited their friends, put their favourite songs on speakers and spent entire afternoons flying kites, dancing, singing and eating.

Away from the core cities, in the villages in the Valley, people flew kites in open fields. Like Dibya, who set his kite for flight from the banks of Godavari River in Tikathali. Chhauni was also a popular space for flying kites.

Kathmandu’s joy in kite fighting

Bibek pulled his kite down and then manoeuvred it back up so his line touched his opponent's line from below and quickly reeled out his line. The resulting sharpness from the speed cut the opponent's line.

Chaaaiiitttt………

“The greatest fun comes from cutting another kite's string,” writes Tuladhar in his 1996 article “Cutting is the greatest fun” published in magazine Kite Lines. “With its coating of adhesive paste and ground glass, the string is as sharp and abrasive as sandpaper on your opponent's line.”

Nepali kite, Tuladhar says, is made to fight other kites, and describes how a kite line cuts the other.

“The technique is to touch your rival's string and immediately reel out line at high speed,” he writes. “The Nepalese style of kite flying is aggressive, and though the kites look simple, they are strategically designed for bringing down other kites.”

At any given time, like Bibek’s kite above Nhyokha sky, skies above the Valley were filled with raging kites, swinging, coming down and going up as the fighters reeled in and out their lattais in ferocious attempts to bring down other kites.

Meanwhile spectators cheered. “Even passersby stopped to look at the kites,” recalls Tina.

The moment of a kite cutting was accompanied by the sound of chait, and children ran in the direction of the falling kite to grab it and the thread in what was termed as, Dibya says, changa lutne/dhago lutne.

Dhungel always joined in to shout the chait resounding through the locality of Jhochhen and almost automatically his feet sped towards the severed kites' direction.

“‘Oii leave that thread,’ the kite owner would scold me. ‘Why do you pull my thread, leave it right now.’ But I’d continue pulling the threads as the owner continued shouting. Other times I caught the kites that had failed to fly and dropped on the ground.”

The fallen kites got stuck in the buildings, trees or poles, or glided down in the open grounds or paddy fields. Falling kites from the Kathmandu core settled down in Tundikhel covering it. Oftentimes kites fell on the fields to rest upon the lush paddy nearing its harvest.

“Children ran straight into the fields to catch the kite,” says Dibya. "They destroyed the crops by stepping on them. Some farmers chased them, scolding along as they did so and if they caught anyone, they slapped them.”

Love and restrictions on kite

Amidst the raging kite fights high up in the sky, there were apparently also some quieter kites lingering much lower among the buildings or tree lines, for their goals lay in not ruthlessly cutting the threads of other kites but piercing softly through the hearts of their owners' love interests.

During the Rana regime, there were designated public spaces to fly kites, writes Gautam in his article. Referring to oral accounts, he writes that the Ranas were particularly careful to avoid kite flyers around their durbars. This is because love-stricken men tied letters to kites and flew them into the durbars to their love interests among the nanis.

He writes that the kites could be flown mainly on the grounds of Chhauni. Anyone flying kites in any other place and around Rana durbars were arrested.

Pant also recalls love-stricken boys from his time. “Just as kites came in different colours and patterns, so did kite flyers,” he writes in the article. “Some wrote love letters using a few words in “symbolic language” on a plain kite and attempted to land it on the rooftop of the girl they liked. Some simply landed their kites on any rooftop if a girl appeared there and waited for reaction.”

King Tribhuvan among kite fliers

Pande writes in his book: “Once or twice during kite season every year, King Tribhuvan went to Chhauni to fly kites. Legend has it that if the line of the king’s kite was cut, it flew to Lhasa. But since anyone who caught that kite received five rupees, everyone attempted to catch that kite.”

In 2021 news report ‘Bhawanle Chhekidiyo Changa Udaune Aakash’ by Shivahari Ghimire published in Nayapatrika, cultural expert the late Satyamohan Joshi also recounts that “During Dashain, Tribhuvan came to the ground below Swayambhu to fly kites. […] He did not use the same thread to fly kites twice.”

In the same article, Joshi says that the King also went to Budhanilakantha to fly kites and participate in kite flying competitions.

End of season, end of culture

Mohan Krishna Shrestha, 86, was born in Budhanilakantha. Every year, on the day of Haribodhini Ekadashi, he saw the annual fair at the Budhanilakantha Temple. He also witnessed kite fliers gathered in the open fields around the Temple.

“Oh, it’d be a lot of people,” says Shrestha. “They came from all around Bhaktapur, Kathmandu and Lalitpur.”

They flew kites on Ekadashi, Dwadashi and some even until Purnima.

“They took all the remaining threads and kites that had survived Dashain and flew the last kites of the season,” says Tuladhar. “I remember my uncles, relatives and neighbours going to Budhanilakantha with their kites.”

Joshi recalls in the 2021 article that King Tribhuvan also went to Budhanilakantha with his sons Mahendra, Himalaya and Basundhara. He greatly supported and also participated in the competitions there organised by the commoners. If he liked he gave prize money to the winners.

This annual event lost its glory days after the decline in the open fields as buildings began to rise with the establishment of Budhanilkantha School in 1972, Mohan says.

“The event survived in some form until the 1990s,” he says.

But what happened after that?

The end-of-the-season event in the 1990s was also an indication of the end of the age-old kite tradition.

“If I go to my ancestral place in Asan to fly kites, it’s not possible for me to do that today because there are buildings everywhere,” says Tuladhar. “Cityscapes and urbanisation have created the obstacle for flying kites.”

Dibya does feel like flying kites sometimes.

“No space to fly kites today,” he says. “In the old times, there were river banks and open fields. Even if you fly kites, it gets stuck in somebody's rooftop or water tank or somewhere.”

Yesteryear’s kite enthusiasts believe that increasing means of entertainment was another reason for the decline of kite culture.

“When television came, kite flying started to slowly decrease,” says Bibek. “And then mobile phones robbed kite flying even more.”

And so, when his sister Sajani cranes her neck up in the sky today, she rarely sees a kite.

“Those days we heard one chait after another,” she says. “These days you won’t hear a single chait.”

22°C Kathmandu

22°C Kathmandu