Opinion

Hopelessness to hope

The run of challenges has sapped the national spirit, but tomorrow will dawn if we shun cynicism

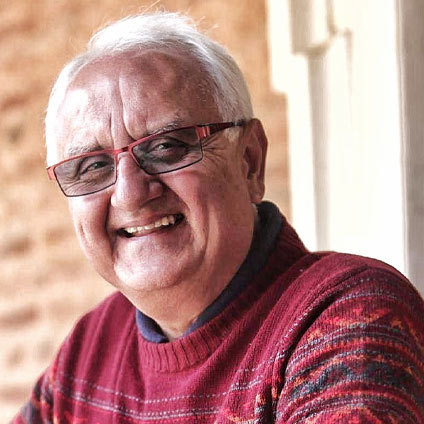

Kanak Mani Dixit

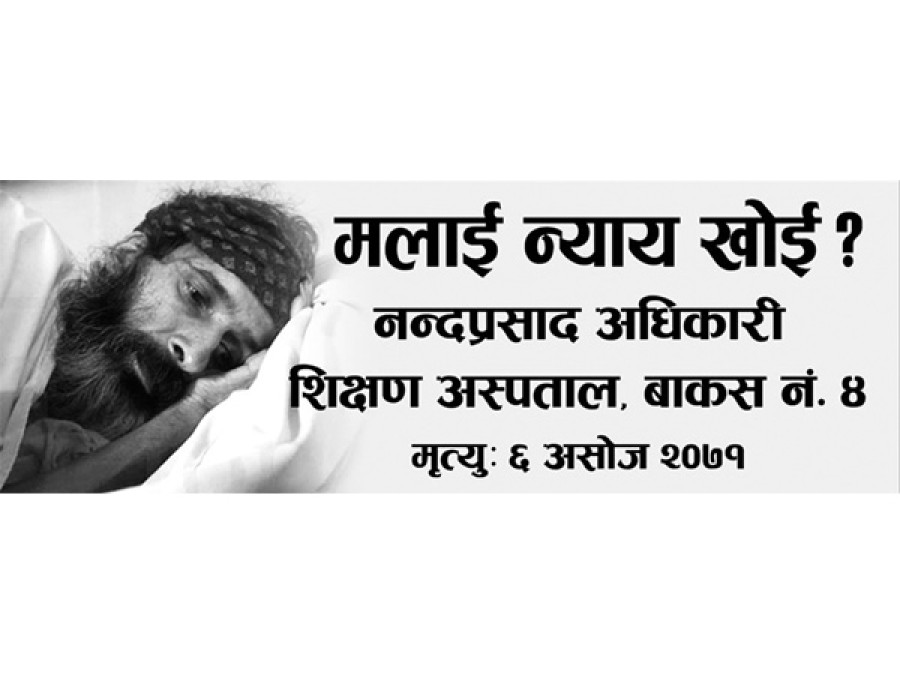

Nothing can describe the hopelessness of the past couple of decades than the death by hunger strike of Nanda Prasad Adhikari, exactly a year ago. And the continuing battle of his wife Gangamaya Adhikari for justice since the murder of their son Krishna Prasad in 2004.

Nanda Prasad and Gangamaya are unique in their steadfast quest for justice, not taking recourse to human rights NGOs and the media and making demands on the government and courts. Coming from the Phujel village in Gorkha, they are the ideal citizens of modern Nepal even though many of us may not have the time to empathise with their insistence that Nepal live up to its promise as a land with rule of law.

Nanda Prasad’s death was the result of a conspiracy between his courage and the state’s cowardliness. Over the course of 333 days of fasting and saline-drip, his frame progressively shrivelled to mere skin and bone, while his eyes remained alert

and accusing.

On the afternoon of September 22, 2014, for the first time, he had a faraway look; he shook his head faintly when a visitor implored him one more time to please take some fluid. By evening, Nanda Prasad was dead, and the state whisked his body off to the Teaching Hospital morgue, where he has remained since in Box No. 4.

Blackmail

It is all too clear why this government of lifelong democrats allowed the worst kind of atrocity to occur under its watch. They were blackmailed by the Maoists, who could not suffer a single investigation of perpetrators of atrocities from their ranks, not the killers of Muktinath Adhikari and Kajol Khatun or the bus bombers of Maadi. This suited the Nepal Army just fine, with its own wish to keep the killers of the Doramba-21 and Dhanusha-5 away from the arms of justice.

The international community, meanwhile, barely uttered a word as Nanda Prasad sank and Gangamaya fought on, signalling shocking relativity in its own application of human rights. The national intelligentsia, the scholars, deep thinkers and civil society stalwarts, all so brash and brazen most of the time, looked the other way when it came to the couple from Phujel.

Nanda Prasad died without seeing justice done, while conscious and daring till the last. Gangamaya has been persuaded to take fluid on occasion since his passing, through the dedicated effort of citizens such as advocate Baburam Giri, human rights activists Charan Prasai and Rashana Pradhan, and conflict-era victims like Sabitri Shrestha and Devi Sunar.

While she had already stopped taking anything for a few days, Gangamaya agreed to hold off till the promulgation of the constitution. The activists had told her that they hoped for some show of courage and commitment in the Attorney General’s Office and the Supreme Court after the signing. But who’s to say what will happen?

Despair for family and society was written all over Gangamaya’s countenance on Wednesday before those gathered outside Bir Hospital to mark the anniversary of Nanda Prasad’s passing: “The Maoists murdered my son Krishna, the government killed my buda. I want to die in my husband’s shirt which I wear, the government can do what it wants with my body.”

The hiatus

Between hopelessness and hope, there is a hiatus, which is where society is right now. The Constitution is out, after one failed Constituent Assembly and halfway through the second. One derives satisfaction from the promulgation. And yet the heart is heavy with the more than 45 deaths in the Tarai-Madhes, and the month-and-half of bandh hitting public services and livelihoods. The national leaders in Kathmandu have yet to reach out to the plains with remorse and empathy.

There is also distress in that Nepal’s new constitution has not been welcomed wholeheartedly by key international actors. There was New Delhi’s tepid response, niggardly enough to ‘merely note’ the promulgation, that too not of ‘the’ but ‘a’ constitution. The UN still seems to labour under the long shadow of Ian Martin of UNMIN, who set the tone of belittling the efforts of Nepal’s democratic parties and the constant scaffolding of the radicals—it merely ‘acknowledged’ the new Constitution.

The polity’s loss of direction is seen in how the National Reconstruction Authority has been left in limbo. As the monsoon bids farewell, by now, we should have been well on the way to rebuilding lives, livelihoods and heritage. But mendacity and mediocrity within the three main political parties has meant that the reconstruction bill was allowed to lapse, and even today, one detects no sense of urgency.

Towards hope

How will we turn the corner? Well, there is the constitution, progressive on many counts, overloaded on others, contradictory and niggardly in places—but providing the basis for a rocky progress nonetheless. Fortunately, the document is easily amendable at least over the next two years and four months, because Parliament picks up where the CA left off.

It being an open society, as it has been since the 1990 constitution, people are free to employ the Twitter hashtag #Notmyconstitution. But a sense of history, comparative politics, and economic imperatives would perhaps have helped these angry ladies and gentlemen to reconsider, they who carry such a simultaneous and contradictory burden of romanticism and cynicism.

Hope will surge if the political parties can bring peace to the Tarai-Madhes population. It will gush if the government can push through local government elections over the upcoming winter or spring. And hope will flower if the national institutions, and especially the constitutional bodies including the courts, settle down finally to do their jobs without threats, pressures and enticements.

The young adults

A key reason to harbour hope is that we now have a category of educated young adults, of the post-1990 generation, who may just rise to the call of society and economy. This was evident in the way they responded to the April earthquake, using skills in IT, access to logistics as well as international contacts for rescue and rehabilitation. As these individuals get positively politicised, might we expect that at least some will take up careers their parents neglected, becoming lawyers, bureaucrats, activists, teachers, journalists, researchers and scholars?

This group of young adults, one hopes, will be idealistic yet practical, so as to confidently bypass the traps of romanticism and cynicism and take pride in the ‘middle path’ if need be.

Meanwhile, a new crop is already filling positions in the international community, professionals with a bit more humility than so many in the previous tranche. Rather than a uni-dimensional vision of Nepal, this group seems to want a better understanding of Nepal and its complex challenges on the road to economic growth, equity and inclusion. Mainly, the new diplodonors will have to learn to distinguish between the carpetbaggers and the society-builders, and understand that easy money can destroy better than it can build.

The boat of the Nepali polity will always rock, but it will have stable enough a keel that we will sail towards prosperity as we implement and amend the new Constitution. And in the new times that lie just ahead, Gangamaya may finally get justice. She is convinced, though, that she will not.

How can we prove her wrong, and also ensure that Nepal finally fulfils the promise of prosperity to its citizens that it has been pending for two and half centuries now? I leave you with the question.

A Farewell

I thank The Kathmandu Post for having provided me with this unique alternate-Friday platform these past three years. Thank you, readers. Those who saw me as too angry and political will understand that I am a product of the times, trying my best to make sense of it all. My columns since August 17, 2012 can be accessed at www.kanakmanidixit.com. Salaam!

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu