Brunch with the Post

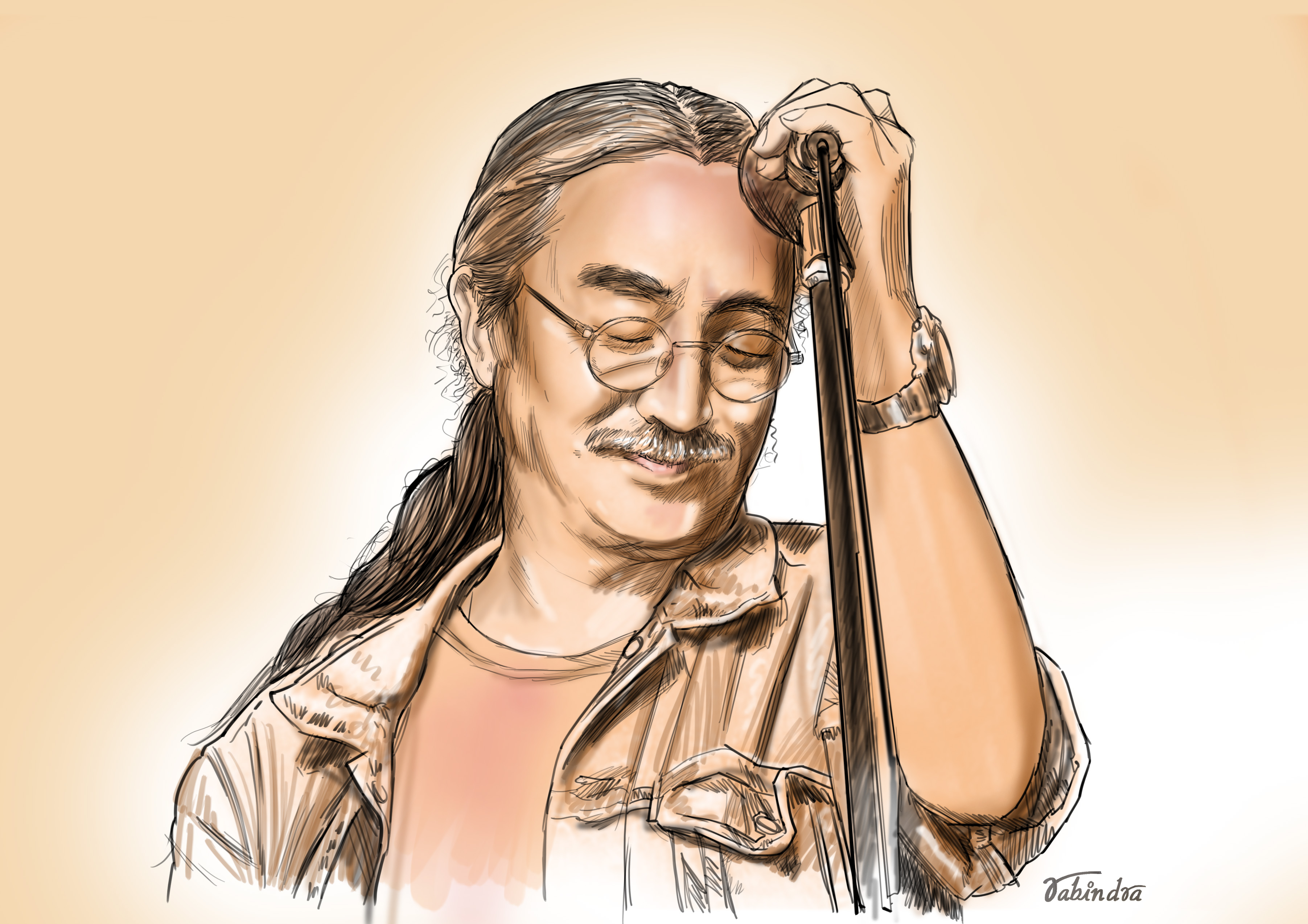

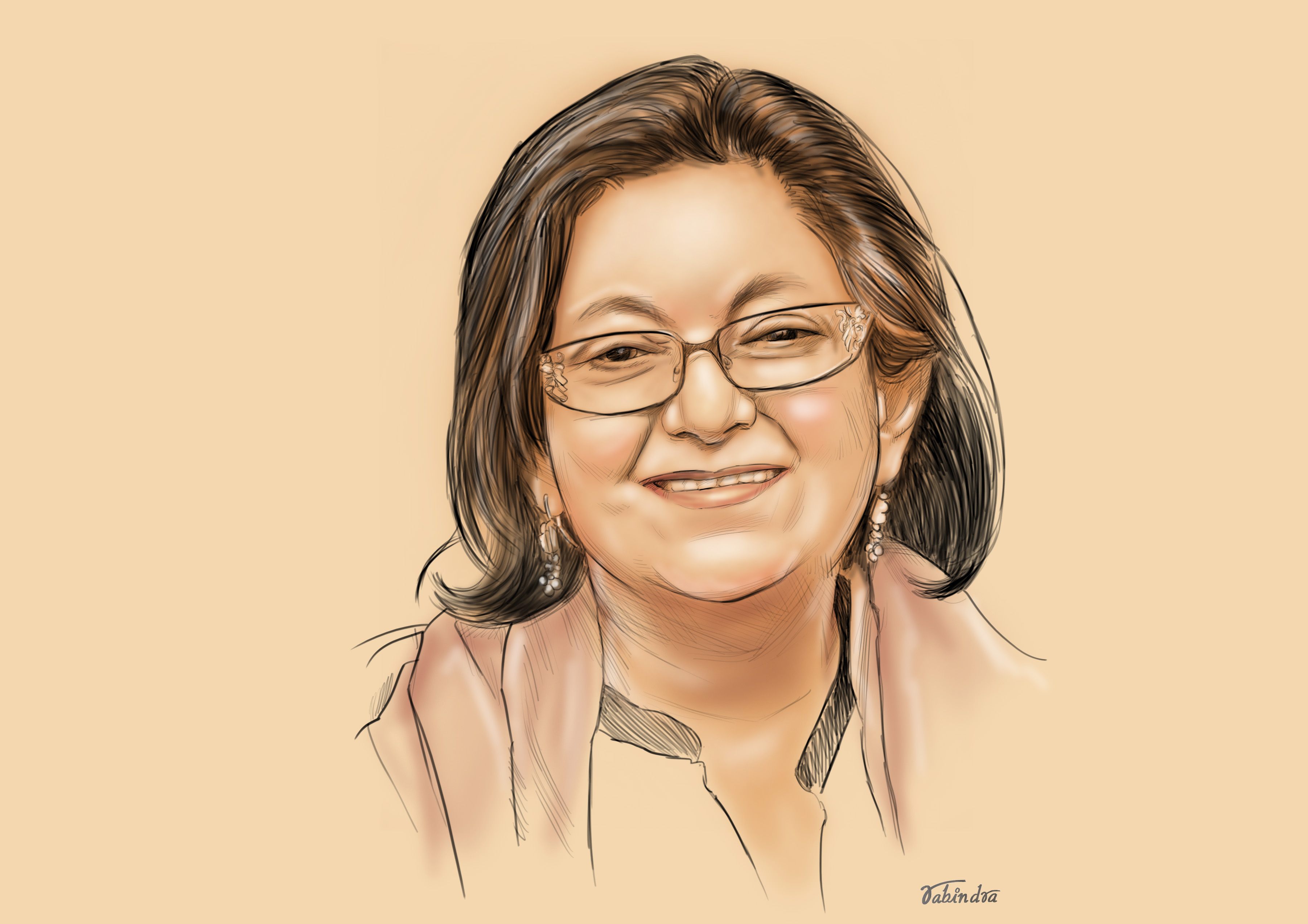

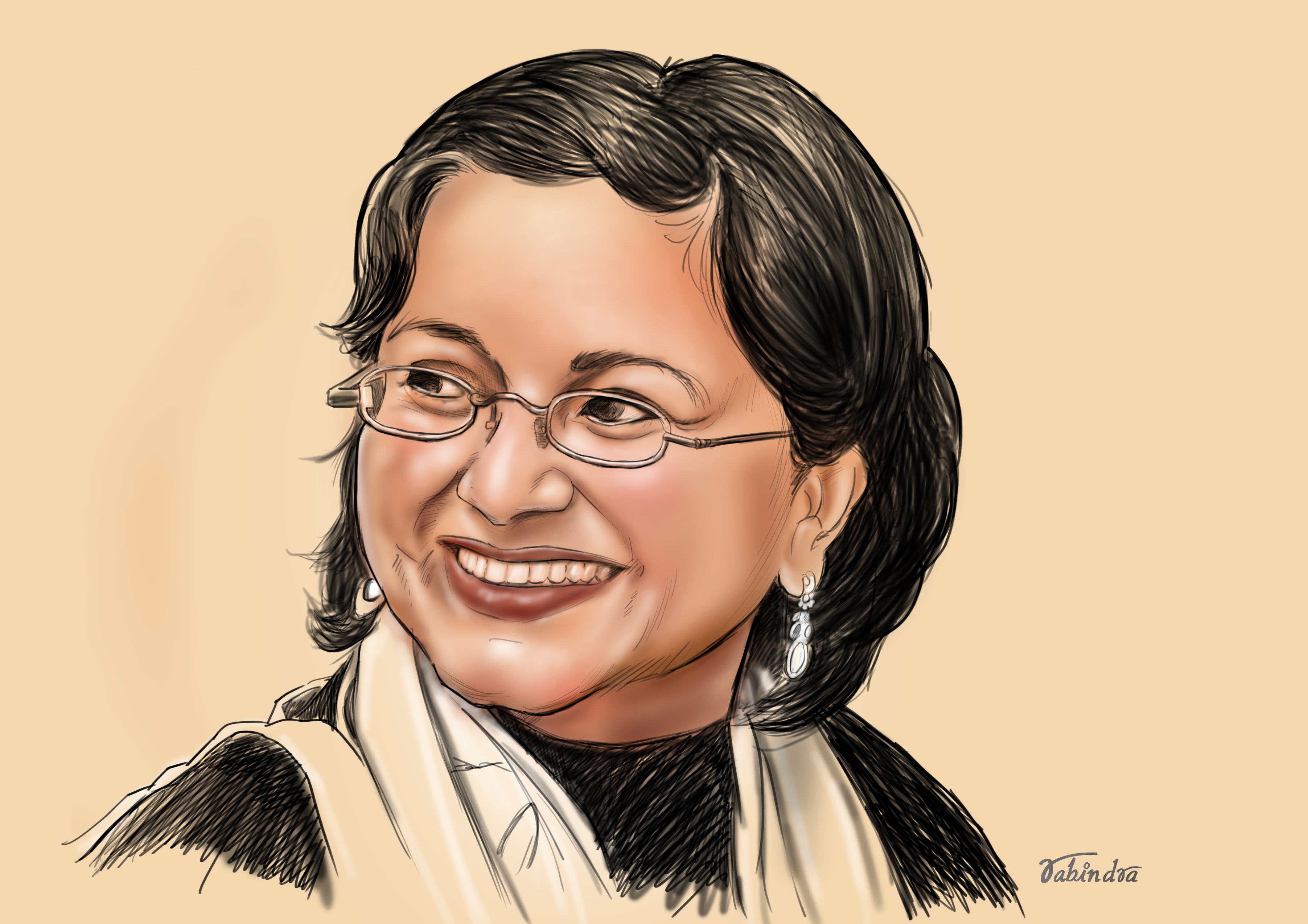

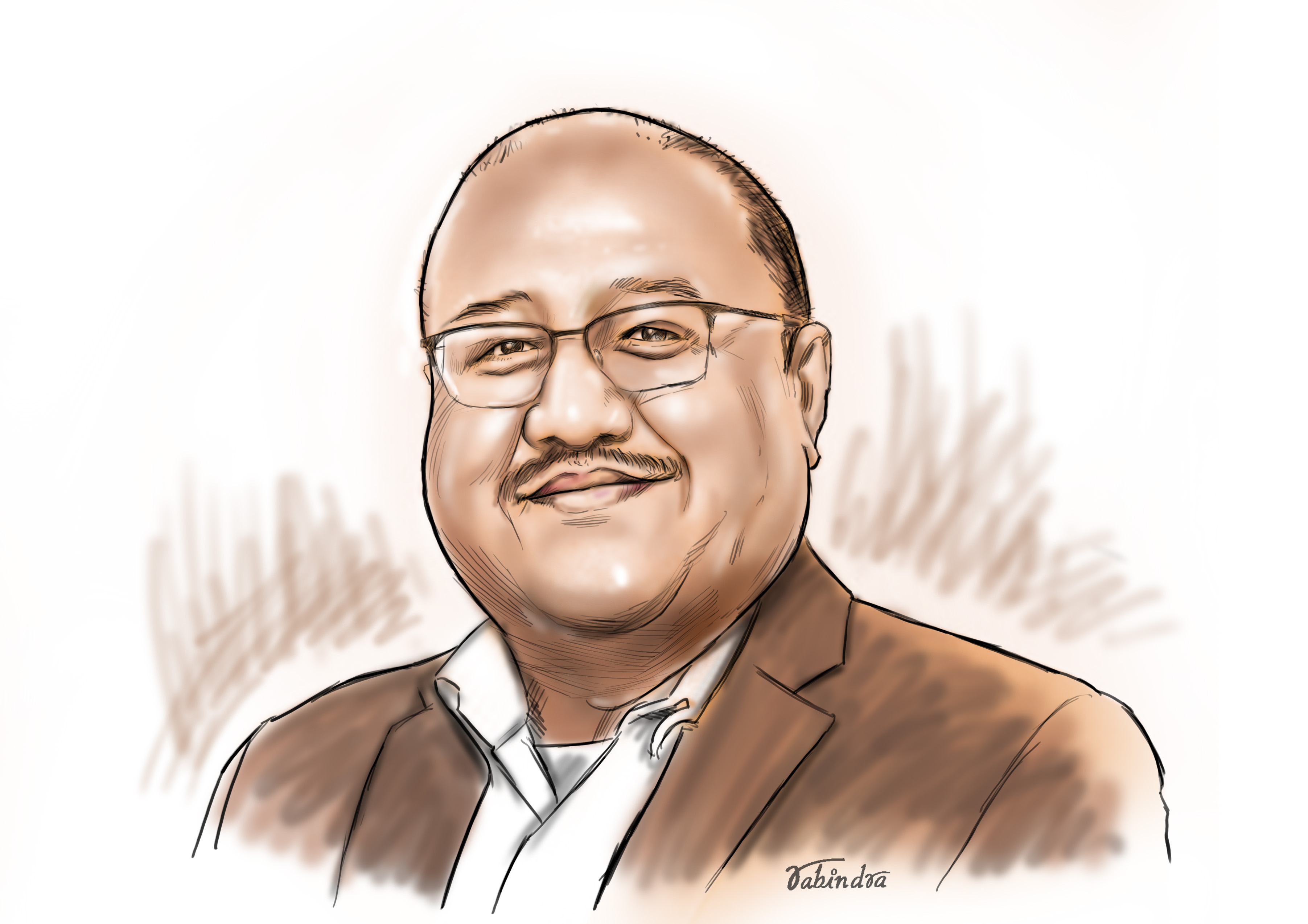

Manjushree Thapa: The content of democracy is social, psychological, emotional

The Nepali-Canadian writer talks about citizenship, her writing and the Nepali political class’s Panchayati hangover.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Growing up as a young boy who wanted to write fiction in English, there were two ‘senior’ writers that we were supposed to read: Samrat Upadhyay and Manjushree Thapa. I read Upadhyay’s Arresting God in Kathmandu and marvelled at its craft, but it was really Thapa’s Forget Kathmandu that left me wondering how it was possible to write with such insight and introspection, and in beautiful prose, about messy and confusing times.

So when I ran into her last Saturday at an event by BojuBajai, I knew I would have to sit down with her. So I asked, and she chose Bhumi in Lazimpat, because, she said, she’s been trying to eat everything that she can’t get back home in Canada.

Thapa famously—or infamously—became a Canadian citizen after the new Nepali constitution came out in 2015. Along with a host of women, Madhesis and Janajatis disillusioned with what the government of the day had called “the best constitution in the world”, Thapa burned the statute and renounced her Nepali citizenship.

“For me, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she says as we sit down at the earthy Bhumi restaurant. “I had had the option of applying for Canadian citizenship for many years but I hadn’t done it because we Nepalis have this sentimental connection to the country. But my relationship to the state broke. I felt that if the state is not going to be loyal to me, I don’t need to be loyal to it.”

Thapa, like many others, took issue with the constitution’s citizenship clause, which does not allow Nepali women the same privileges as Nepali men to pass on citizenship to their children. Many women have argued that this essentially turns women into “second-class” citizens. And four years later, despite much activism and public pressure, the clause has remained.

“The resistance to making the law equal is so deep,” says Thapa. “There is so little shame in saying, ‘no it’s not sexism, it’s about racism.’ I don’t know how we’ll break through that.”

The argument against granting women the equal right to pass on citizenship comes from many who say that this will allow Indians from across the border to easily acquire citizenship and then flood Nepal.

“The closer you are to the state, the more you buy into this racist logic that Nepal needs to be protected from Indians through the wombs of Nepali women,” says Thapa.

It is this issue that forms the theme of Thapa’s next novel.

“Broadly, it’s about the citizenship issue. That’s the theme but it’s a story of people,” she says. “In Hindu aesthetics, when you make a stone sculpture, at some point you have to bring breath or life into it. That’s what I need to do now. The story is all there but it’s not breathing yet.”

I ask her why she chose to write a fictional novel about the issue when it could easily have been a non-fiction take, much like her essays in The Lives We Have Lost. Her most celebrated book is Forget Kathmandu, a nonfiction account of the 2001 royal massacre and the Maoist insurgency years.

“I could definitely write non-fiction about this,” she says, as a Newar feast of bara, chatamari, fried fokso and aloo tama arrives. “But for this book, the voice that came to me was a fictional voice.”

Thapa admits that she misses fiction. She last translated Indra Bahadur Rai’s Aaja Ramita Chha as ‘There is a Carnival Today’ and her last book was All of Us in Our Own Lives, a novel that skewers the development and aid industry in Nepal.

“I miss non-fiction because it is a lot less tortured,” she says. “Non-fiction doesn’t have that inner imaginative work that you have to do for fiction. So it’s not always full of self-doubt, unlike fiction where there are always questions about why this character, why this sentence, why this word choice. It ends up being really fraught as an emotional process. Non-fiction is more straightforward.”

Non-fiction, especially when it is personal, also runs the risk of being too self-involved, she says.

“It becomes a question of asking if my voice is the best way to tell this story. When it comes to citizenship, I am not the primary victim so it is more important to tell it from the point of view of someone who is,” says Thapa. “Citizenship affects Madhesi women, and other women and their children.”

Thapa has been working on the book for some time, but she had to put it on hold when her sister Tejshree Thapa, the human rights lawyer, died.

“It was such a profound loss. The person I was before and the person I am now feels different,” says Thapa.

That’s one of the reasons Thapa is in Nepal at the moment. She is focusing on family and on taking care of things emotionally, she says. Writing can wait.

Since she arrived, Kathmandu has been in a furore. First, it was the arrest of the rapper VTEN for promoting “anti-social values” and then it was Kalapani, a territory that Nepal claims but India refuses to give up. What does she make of these developments, especially the KP Sharma Oli government’s increasing stifling of artistic expression and freedom of speech?

“Our political class was educated during the Panchayat era,” says Thapa. “So even though they brought us democracy, some of the national myths have been inculcated into them. They broke the political form but the intellectual content of the Panchayat still has a hold on their imagination.”

This, according to Thapa, explains the political class’s fascination with China, which has essentially managed to do what Mahendra set out to with the Panchayat--a homegrown model of development, with less of a focus on human rights and freedoms.

So perhaps it is the older generation’s discomfort with the manner in which the younger generation is taking up issues and speaking its mind. For a political class that grew up idolising Maxim Gorky’s polemical novel Mother, it is not unnatural that ‘Hami yestai ta ho ni bro’ makes them uncomfortable. The communist belief is that art should serve the revolutionary cause but for many young people of today, art is for art’s sake.

“The public discourse has really opened up in the last few years, with the kinds of subjects that people are willing to talk about, like body issues and sexuality,” says Thapa. “This is the effect of young people finding a voice and not being silenced by the onerous old generation.”

Thapa says the literary and journalism world has become very young, and there’s a fatigue around politics. “The content of democracy is social, psychological, emotional,” she says, “and the younger generation is paying more attention to these more subtle layers of a democracy.”

But is it the same with writers? Nepal’s literary tradition has long been socially conscious, with social realism as the leading literary school for the Nepali novel. Thapa says she hasn’t managed to read much new Nepali writing but she is building a list that she will get through. Her favourite Nepali writers still include an older generation--Bimal Nibha, Shrawan Mukarung, Narayan Dhakal, Khagendra Sangraula.

I ask her if she feels like there is a divide between Nepalis who write in Nepali and Nepalis who write in English. As someone who writes in English, I am often told that this divide exists, not just in fiction and non-fiction but also in journalism, theatre, music and other art forms. But Thapa disagrees.

“I don’t think there is a divide here. In Delhi, there’s very little crossover,” she says. “Here, there’s so few English writers to begin with and most of them are quite in touch with what is happening in Nepali literature.”

As we talk more about writers and writing, I ask her if it’s true that in order to write about Kathmandu, you need to leave Kathmandu.

“In Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, there are two characters, one who ends up leaving the country and has this lightness, and another who is so tied to history,” Thapa says. “Right now, I’m more on the lightness side. The emotional and imaginative benefits and overall life benefits of being untethered are great. But in the past, and in terms of how I’ve formed as a writer, it has always been the other one, where I’ve always been involved in the historical processes that I’m living in the middle of. It has always been a balance of the two.”

ON THE MENU

Bhumi, Lazimpat

Aloo tama: Rs 120

Vegetable and egg chatamari: Rs 150

Chicken and egg bara: Rs 150

Fried fokso: Rs 200

Hot lemon with honey: Rs 110

Americano: Rs 120

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg)