Brunch with the Post

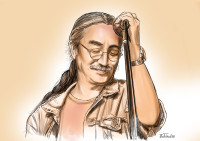

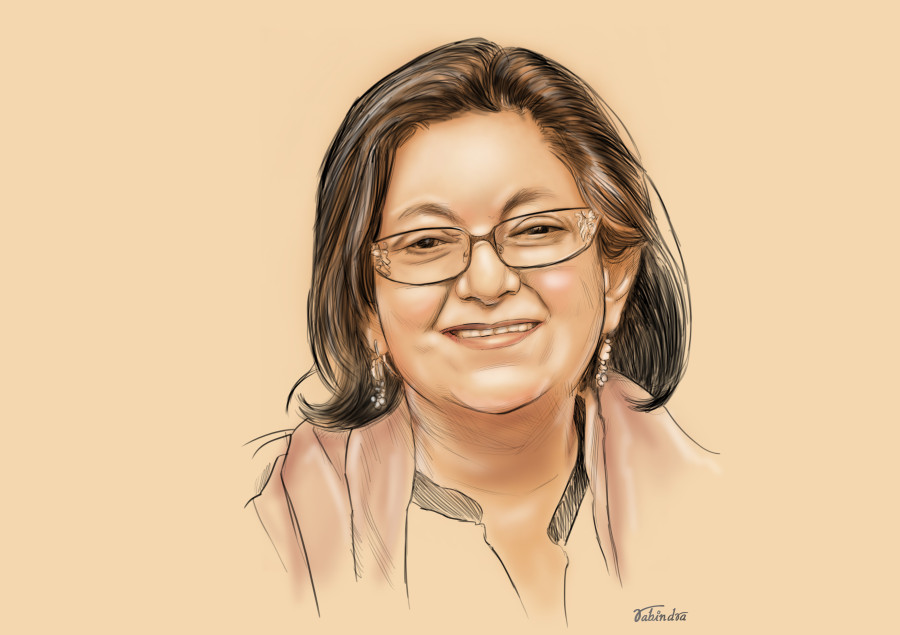

Namita Gokhale: Borders change; cultures suffer amnesia; but literature unites

The writer and co-director of Jaipur Literature Festival speaks about the ties that bind South Asia together and the power of literature.

Pranaya SJB Rana

“My body is a haunted house,” laments the tortured Rudrani Rana. A descendant of Dev Shumsher, Rudrani is haunted by the ghosts in her family, especially the “monster from the past”, her mother. Rudrani, like many of us, has a book in her that she wishes to publish.

In Namita Gokhale’s new book, Jaipur Journals, Rudrani’s story is one of four that intersect and deviate, providing a glimpse into the fictionalised lives of the writers—and future writers—who come to attend the Jaipur Literature Festival.

But for Gokhale, who is co-director of the festival, there is something about Nepal and Nepalis that leads her to revisit this space, time and again in her books.

“I feel very much at home in Kathmandu. I come from Nainital, a place that was colonised by Nepal,” she tells me with a laugh over morning coffee at the Hyatt.

Even her last novel, Things to Leave Behind, includes a sizable chapter on Kathmandu, while The Himalayan Arc, a collection of writing that Gokhale edited, includes contributions from numerous Nepali writers on and around Nepal.

“I feel a sense of recognition when I come to Kathmandu as there was a porous continuity in the culture,” she says. “There's a vibrant and cosmopolitan cultural curiosity in Kathmandu. It is the oldest Himalayan capital and a city of immense history, which one tends to forget.”

Gokhale, one half of the duo (alongside William Dalrymple) that runs the Jaipur Literature Festival, was supposed to be here last year for the Nepal Literature Festival, Pokhara’s very own lit fest. But she says she couldn’t make it because her daughters were both pregnant and her grandchildren on their way. It is understandable that Gokhale is taking some time out for her family, as putting on the biggest literary show on earth cannot be a quick or easy task.

This year was the Jaipur Literature Festival’s 13th year and in the years it’s been operating, it has expanded to eight international editions and regularly hosts the most storied names in literature. Thousands attend, and I am wondering just how Gokhale manages to pull it off every year.

“The reason I pull it off is that ‘we’ pull it off,” she says. “There's a wonderful partnership with the Sanjoy Roy and his absolutely inspirational team at Teamwork Arts. My co-director William and I represent a different range of interests and we trust in each other's instincts. He has a special interest in history, the arts and is deeply connected to the international literary world while my special interest is the richness and diversity of Indian language literature as well as searching underrepresented voices everywhere.”

Gokhale has been attempting to bring a wider range of Indian literature, besides just Indian writing in English, to Jaipur, as she believes in the need to preserve India’s thousands of dialects and hundreds of mother tongues. In that regard, translations can be a very useful tool.

“We have to watch out for oral literature, the dialects, as they contribute so much to India’s unique literary heritage,” says Gokhale. “I want to keep those stories alive and in conversation. There is also the need to have the Indian languages in dialogue with each other, to sidestep the hegemony of both Hindi and English. English continues to serve as a bridge language for translations.”

In Nepal too, there have been a number of excellent translations, like the recent rendition of Indra Bahadur Rai’s There’s a Carnival Today by Manjushree Thapa. There is a movement building towards translations, and to bring international literature into Nepali. Kannada writer Vivek Shanbhag’s Ghachar Ghochar was recently translated into Nepali.

Translations are intrinsic to cultural exchanges, which have been going on for centuries in this part of the world. This intermingling has led to commonalities across South Asia.

“Kumaon, where I am from, has deep connections with Nepal but when I edited The Himalayan Arc, what we discovered is that the shadow—a benevolent shadow—of Tibet and the Bonpa culture hung across the Himalayas, even though the present realities might have changed,” says Gokhale, going to provide more examples of South Asia’s cultural similarities. “Sindhi literature unites Pakistan and India, as does Urdu, which now belongs to Bollywood as much. Tamil literature binds Sri Lanka and India and even places like Singapore. Malayalam is huge in the Middle East, because of all the migrants. Nepali is a sort of glue across Northeast India. Borders change; cultures suffer amnesia; food and language divide; but literature unites.”

Gokhale says she is fascinated by language and literature, especially multilinguality, bilinguality and literary diversity.

“Sometimes, the mother tongue is quite literally the mother's tongue,” she says. “For instance, at the launch of Prajwal Parajuly's first book, The Gurkha's Daughter, I persuaded him to read out a portion in Nepali. He got his parents to translate from the English. The book is out now in Nepali, titled ‘Gurkhaki Chhori’. Again, my friend Chandrahas Choudhury writes in English but his mother tongue is Odia, and it is his mother who has translated his novels into Odia.”

At Jaipur, Gokhale has made sure to include a diverse range of voices, including Nepali from both India and Nepal. But the festival has not come without its own controversies. There has long been criticism of the festival’s title sponsor, Zee, for what many allege is ‘propaganda’ and a conservative right-wing slant on the news.

“We are supported by Zee Entertainment,” says Gokhale. “I must say that they have been responsible as sponsors. They have never once tried to push any agenda or to impose upon us in any way.”

This year, as protests against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act continued across India, there were some who also tried to protest at the Jaipur Literature Festival, only to be led away. What happened there? I ask.

“As organisers we have a responsibility to our speakers and visitors that the festival is run smoothly and without disruption. We knew that there could be protests within the venue and we had requested them to do so outside the festival premises,” she explains. “I am personally supportive of those who had raised their voices. In fact, even as they were protesting, there were three jam-packed sessions including one on Faiz [Ahmad Faiz] and Firaq, that echoed these very sentiments. “

Gokhale has weathered much criticism over the years and she takes it in stride. Every year, given the scale of the event, there is someone or the other who has a gripe or a complaint, justified or not. But Gokhale keeps an open mind.

“I listen to everyone,” she says. “Jaipur provides a platform for people to listen to each other. So much of our thinking is formed by assumptions, reactions and prejudices. The truth always lies between many perspectives. Sometimes, there is only one truth and then you have to stand up for it when it is under assault. But reaching a nuanced understanding of the truth involves listening in.”

Perspectives are the prerogative of the writer. The very best of writers are often able to present multiple perspectives alongside each other, without privileging one over the other, as the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin pointed out in Dostoevsky’s works. And in addition to Gokhale’s work as a festival director, she is also a writer, which she calls her primary vocation.

Given the controversy this year at the Jaipur Literature Festival and the protests that are still ongoing across India, I want to know how artists and writers should respond. What role can writers like her play in the trying times?

Gokhale is very firm in her answer.

“I think it is an absolute presumption for me to think that I have a role,” she says. “All of us contribute what we can in our own small ways. I put in my best both at a personal level and at an institutional one. I am a writer, first and foremost, and I think the role of the writer is to write what one is driven to write.”

Her answer goes against the grain with what seems to be a general expectation of the arts in Nepal, that there should be a ‘message’ or a ‘moral’ to art. This, I believe, comes from a very Marxist understanding of the arts, as something that should serve a higher ideal, as opposed to the bourgeois ‘art for art’s sake’.

“Far too many writers are speaking from the pulpit, which may work for them, but for me, I write things that may be whimsical or absurd, but things that I have to work out for myself. I don't have an ideological view of what a writer must do.”

Gokhale seems to believe in literature as a kind of therapy, where you work out issues, personal, social or existential, through your writing. This assessment is bolstered by what she says happens when she finishes a book.

“When I finish a novel, I get complete amnesia on what I have written. I even forget the names of my characters,” she says. “My last novel was called Things to Leave Behind and life is all about things to leave behind—as a legacy or as baggage.”

For Gokhale, writing is personal. It is a task that you set upon yourself and you work out with yourself. It can be arduous and it can be torturous but ultimately, it is a test against yourself. But she has a more optimistic outlook on the process.

“When I write,” she says, “I am talking to myself and I find myself extremely interesting company.”

ON THE MENU

HYATT REGENCY, BOUDHA

Americano: Rs400

Cappuccino: Rs400

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)