Brunch with the Post

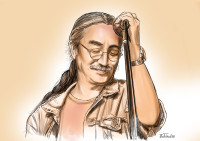

Amun Thapa: Don’t expect Nepalis to support you if you have an inferior product

The e-commerce entrepreneur talks about competing with one of the largest companies in the world and the cost—and benefits—of doing business in Nepal.

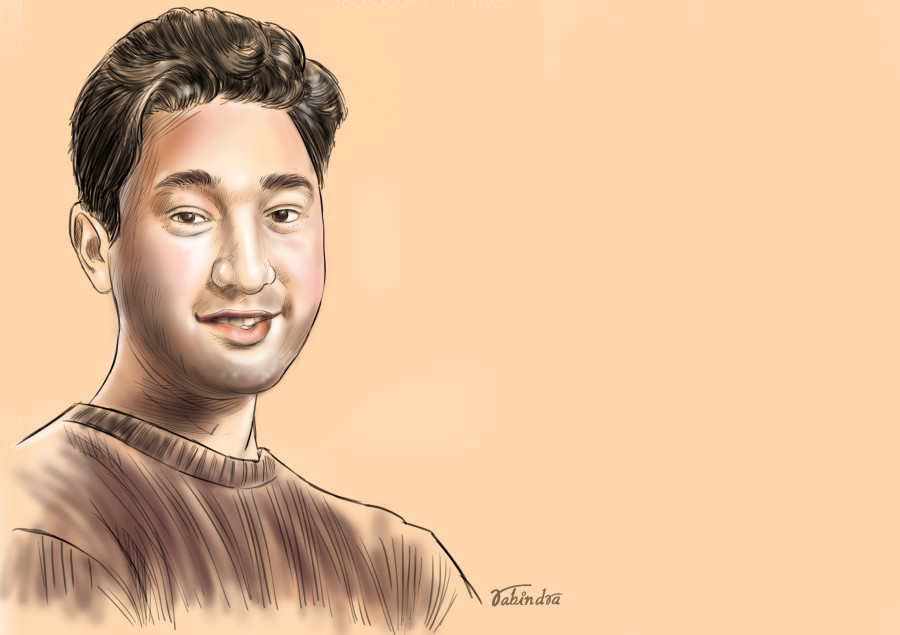

Pranaya SJB Rana

In 2018, when the Alibaba Group acquired Daraz, the entire e-commerce industry in Nepal let out a collective gasp. Alibaba is one of the largest companies in the world with e-commerce as its central business and its entry into Nepal meant big things for the online retail industry.

For homegrown e-commerce outfit Sasto Deal, Daraz now presented a significant challenge.

“It came as a big surprise,” Amun Thapa, founder of Sasto Deal, tells me as we sit down for lunch at Evoke in Jhamsikhel. “But I was also happy for the industry.”

I have known Thapa for a long time—we went to school together. It was nearly 10 years ago that he told me of his plans to start a e-commerce company in Nepal. In 2011, he did just that, founding Sasto Deal as a website that provided deals, like GroupOn. But Thapa quickly moved on to retail, as he realised that that was where the market was. By 2018, he was just settling in as a significant leader in e-commerce when the news came in.

“Alibaba entering Nepal was big news,” he says. “But the first thing I had to do was motivate my team—and myself. The first example I gave was of David vs Goliath.”

People were watching to see how Sasto Deal would compete against a company backed by the resources of a leading retail giant. But Thapa refused to compete on their terms.

“It would be foolish to compete with a company where they are stronger,” he says. “Alibaba's 11.11 sales in 2019 were bigger than Nepal's entire GDP.”

In 2019, Alibaba’s 11.11 sales were $38.4 billion; Nepal’s GDP in 2017 was $29.04 billion, according to the World Bank.

There was no way a Nepali company can compete with resources of that size.

“If we try to compete with them in terms of capital, they will always have more capital. If we try to compete in terms of technology, they will always have better technology,” says Thapa. “But we're the local players and we have certain advantages. We know the market better.”

Thapa cites Daraz’s 11.11 sales event as a case in point. November is a bad time for shopping in Nepal because most Nepalis spend their Dashain bonuses during Dashan and Tihar. By the time November comes around, most Nepalis have already gone on their yearly spending spree.

“A guy in Surkhet doesn't know what 11.11 is but he knows that Dashain is a time to buy new clothes and spend money,” says Thapa. “Dashain and Tihar have centuries of branding, which cannot be replaced no matter how much money you spend.”

Sasto Deal’s strength is that it is a local company, says Thapa, and he wants to address very local issues. E-commerce is still in its infancy in Nepal. Online payments remain difficult, despite the success of digital wallets. According to Thapa, e-commerce accounts for barely 2 percent of the total retail market, but it has potential.

“The TAM [total addressable market] in Nepal is worth $1 billion,” he says. “E-commerce is the biggest and fastest growing industry in the world, but it is also the most misunderstood.”

The misunderstanding primarily has to do with investments. Local investors either do not understand e-commerce at all or think that it provides a quick profit. But as Thapa points out, Amazon didn’t make money for 20 years.

“Jeff Bezos could’ve made millions but he wanted to make billions,” says Thapa. “But in order to make that jump, you have to be willing to lose money in the short term.”

As most local investors are wary of digital ventures, most start-ups have to look elsewhere for seed money, and that by itself is a whole different deal.

First, the government has raised the minimum foreign direct investment amount to $500,000 from $50,000, in order to “attract investments that would support large-scale projects.” But for start-ups forced to look outside because locals are unwilling, this has been a death sentence.

“The average ticket size for most start-ups is $100,000 to $200,000,” says Thapa. “A few industrialists who wanted to protect their own business lobbied to get this passed and now, start-ups are dead before they even get going.”

For the ones that do manage to get this level of funding, there’s yet another seemingly insurmountable hurdle—bureaucratic red-tape. Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli has boasted about Nepal’s performance on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, where Nepal climbed 16 places from 110 in 2018 to 94 in 2019. But many businesses tell a different story.

“The government has said that foreign investment will be cleared in 15 days but if you ask any startup, they will tell you that it actually takes 10-12 months,” says Thapa. “In that time, the startup will die without funds.”

What Nepal needs in order to lure investors here is a good success story, Thapa says, echoing what Biswas Dhakal, founder of eSewa told me last year.

Nepal needs an example of a successful start-up company that has made it big,” he says. “Almost every country around the world has brands that they are proud of. India has TATA, Sri Lanka has Dilmah. But Nepal has none. It doesn't have a good story to tell. There's no exit, no proper funding, and everything is a hassle.”

There might not yet be a big success story but there are a number of Nepali startups that have slowly built a niche for themselves. Apps like Foodmandu and Tootle have managed to tailor global solutions to Nepali problems. Foodmandu might be safe for the time being but Pathao, the Bangladeshi company, is giving Tootle a run for its money.

“One thing I'm really thankful to Daraz for is that they've shown me what world-class is,” says Thapa. “My vendors had been using Sasto Deal's vendor panel to upload their products to our website for so long without any complaints. But the moment Alibaba came into the picture, vendors saw how easy their vendor panel was and then they started complaining.”

Competition like this is healthy, says Thapa, because it raises the standards for the entire industry and ultimately, it’s the customers who benefit. But that is also why Nepali companies need to step up; they cannot be complacent and be satisfied with the fact that they’re “good enough” for Nepal.

“It's not like I was a bad company, I was good for the market but an international company showed me what world class is,” says Thapa. “As a Nepali company, your customers will always have a soft corner for you. If you can match the experience of a foreign company then the customers will pick the local company. But don’t expect Nepalis to support you if you have an inferior product.”

But as I see it, Daraz is outperforming Sasto Deal and if something drastic doesn’t happen soon, the battle might be lost.

“We have a plan,” says Thapa. “For the past six months, we've been working on a deal with a very big company. We've already signed the agreement and we're going to make an announcement very soon. It is going to be big news for the country and will not only give us a competitive advantage but will also uplift the industry.”

But moving forward, Thapa sees a big risk ahead, and it is a very pragmatic concern.

“There's a big digital divide in Nepal, which is only going to increase as e-commerce takes off,” he says. “Those who know how to go online will benefit while those who don't will get left behind. Companies in Kathmandu know how to do this and are moving away from traditional retail to selling online but for SMEs [small and medium enterprises] in rural areas who still depend on customers walking into their stores or they themselves going to the bazaar, they're going to be left behind and that's what worries me.”

This is why he wants to focus on expanding the reach of e-commerce from outside the big cities to tier 2 and tier 3 cities and also rural areas.

“SMEs have the potential to contribute 40 percent to the GDP but in Nepal, they are only contributing 10-20 percent,” he says. “I want to change that. I want products from Dolpa to be available all over the country, and outside Nepal too. We need to bridge the digital divide by bringing SMEs from all over the country into the e-commerce system and helping them access a market that is nation-wide.”

Sasto Deal already has a section that promotes Nepali products, although there aren’t many options. But Thapa is working on it. Just recently, he got a call from a Palpa-based dhaka entrepreneurs association who wanted help promoting their products, he says.

Thapa sees e-commerce as the future of retail and given Amazon’s global dominance, he is probably not wrong. And as new players enter the field and the industry standards rise, the market is certain to grow.

“In the next few years, e-commerce is going to be a lot bigger as more customers and sellers join us, but it is also our responsibility to help the community,” says Thapa. “I'm not here just to make money. I'm a local entrepreneur and I'm here to stay. I was born here and I'm going to die here so I need to serve the market that's here.”

ON THE MENU

Evoke, Jhamsikhel

Fresh lime soda Rs 125

Americano Rs 150

Vegetable steak Rs 700

Aglio e Olio Rs 500

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)