Brunch with the Post

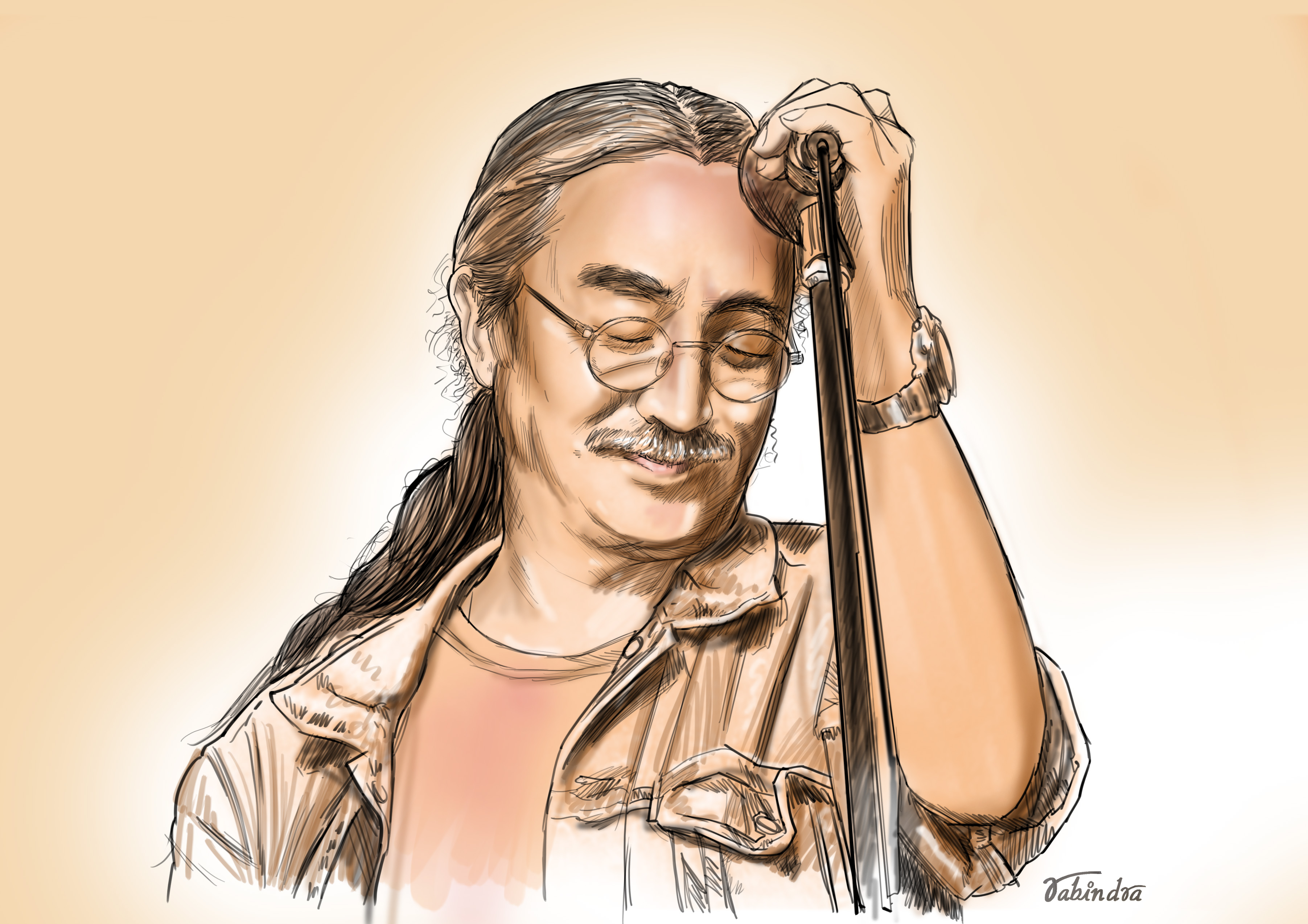

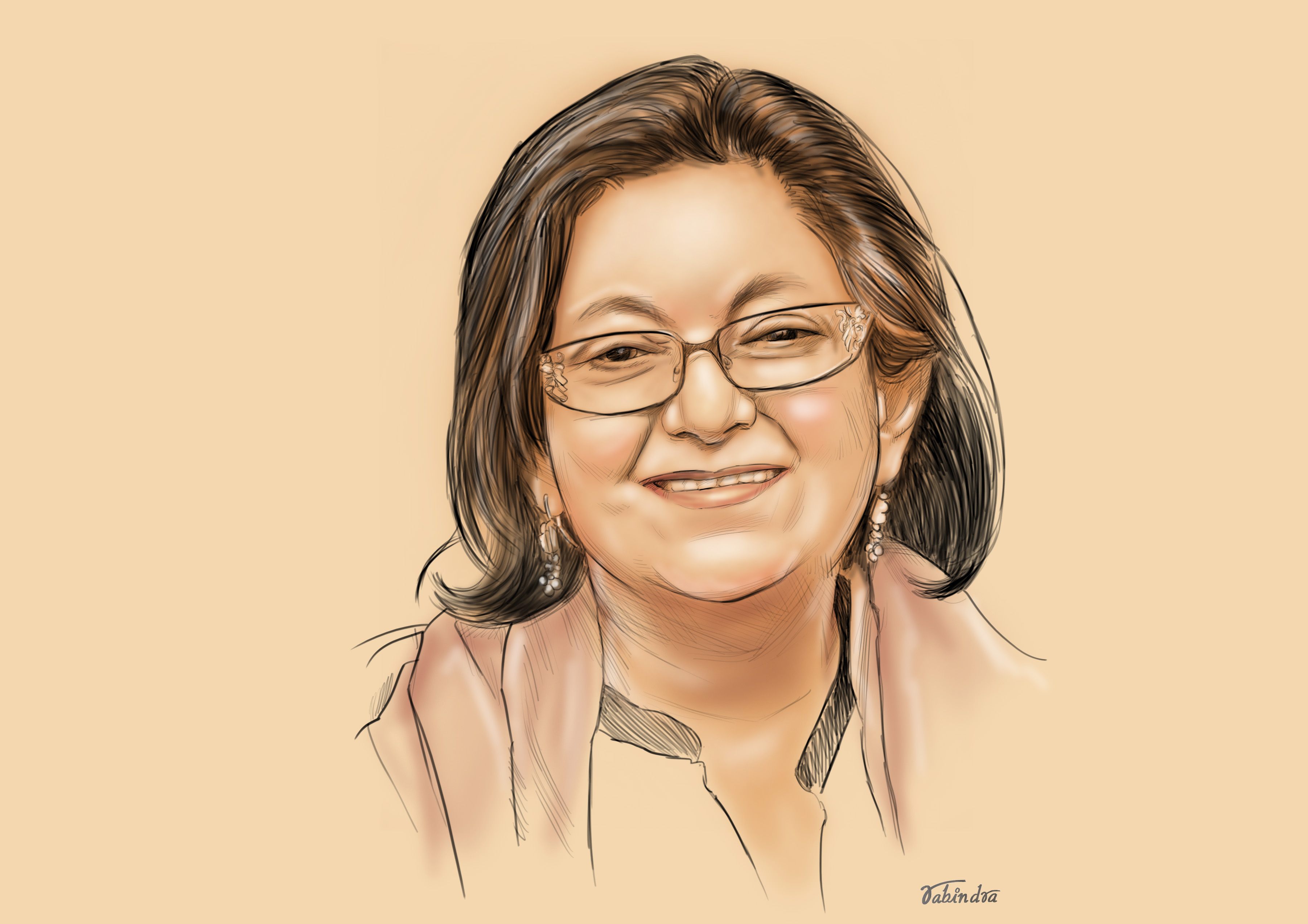

Mallika Shakya: The middle class is not creative, original or passionate

The economic anthropologist talks about regionalism, the failure of SAARC and labour politics in Nepal.

Pranaya SJB Rana

It is a cold rainy winter morning when I meet Mallika Shakya at the Japanese U Cafe in Bakhundole. The South Asian Games has just ended and there is protest brewing in India over the national register of citizens and the citizenship amendment bill. This seems like a good time to talk about Nepal and its place in South Asia, and Shakya, who is an assistant professor at South Asian University in New Delhi, is the perfect interlocutor.

We begin by talking about the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, or SAARC, which just marked its 35th anniversary. Shakya has written about SAARC before and she hasn’t been exactly kind.

“The problem with organisations like SAARC is that they ignore the everydayness of life,” says Shakya, as we place our order for hot soups. “The question of nationalism for me and for many others is not about passports, wars and borders but more everyday things. There is a shared cultural, historical, and political aspect to this region, but instead of acknowledging this, SAARC relies more on how the leaders are doing.”

In its 30 years of existence, SAARC, most analysts would say, has been largely ineffective. It has little to no power over any of its members, let alone India, the giant in the region when it comes to just about any indicator. The India-Pakistan rivalry has held SAARC hostage, say many analysts, but India is having problems of its own.

Shakya is a professor at a university located physically in Delhi but born out of a more utopian view of regionalism. Before coming to South Asian University, which is funded by all the governments of South Asia, Shakya was at the University of Pretoria in South Africa. So she recognises that the crisis of regionalism is not just a South Asia problem; it is something that’s occurring all over the world, like with Brexit in Europe.

“Clearly, we’ve elected the wrong people,” she says, as her jhol momo arrives. “I think we are too kind and too forgiving. Once you’ve made a very abhorrent mistake, like Gujarat, people should have said enough is enough, but things went all the way to election and reelection.”

Shakya, of course, is talking about India’s Hindu-nationalist prime minister Narendra Modi and his role in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Modi has now plunged India into a crisis. But whether it is Modi in India, Donald Trump in the US, Boris Johnson in the UK, or KP Sharma Oli in Nepal, democratically elected leaders are hollowing out the very process that led them to the top.

“The election of these kinds of people shows the kind of politics we believe in,” says Shakya. “As voters, as citizens, we are so forgiving of people who preach one thing but practice another. Honesty has been taken over by showmanship, oratorical power and populist aggression.”

What is common in most of these leaders is not just their populism, but also their promises--of economic revitalisation in the case of the US and the UK and economic arrival in India and Nepal. Promised with progress and development, voters have been all too willing to look the other way when rights are trampled and freedoms circumscribed.

Shakya, who is an economic anthropologist teaching sociology, knows just where this came from--the 90s and the economic engineering of the Nepali Congress. Her book Death of an Industry: The cultural politics of garment manufacturing during the Maoist revolution in Nepal traces how Nepal’s once-booming garment industry fell victim to the vagaries of international monetary policies and organisations, aided and abetted by a Nepal government that was only too happy to cater to them.

Shakya identifies, in particular, the Nepali Congress as the architect of Nepal’s economic liberalisation.

“The opposition within the Congress was oppressed by Ram Sharan Mahat and his school of thought,” says Shakya. “At that time, he was such an important man for the IMF [International Monetary Fund] and World Bank.”

Although led by an ostensibly socialist political party, Nepal’s economy quickly went through privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation. Private interests benefitted and crony capitalism became entrenched but it was workers who suffered.

“The proletariat became the precariat. There was a schedualisation of labour, which was called flexibility. The ‘doing business index’ was played up where it was believed that if it is easy to hire and fire people, productivity will increase,” says Shakya. “The Nepali Congress did not wish to do anything that would hamper productivity, so casualisation has now become the norm.”

Casualisation is when the workforce goes from having permanent jobs to having temporary or short-term work. This leads workers’ lives to become precarious, where they have to live without job security or economic safety.

“Even in the worker imagination, casualisation was cast as ‘having more freedom’,” says Shakya. “Workers don’t know if they will have a job after Friday but that uncertainty was being sold as freedom.”

But in Nepal, the majority of political parties are either communists or socialists, and they all have trade unions, which are supposed to work for the rights of workers. But according to Shakya, that by itself is the problem--there are too many unions.

“There is free competition between the trade unions,” says Shakya. “The UML had GEFONT [General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions] and the Congress’ trade union, after Mahat, would say that we will bargain for workers’ rights as long as it doesn’t hinder productivity. The Maoists too had their own revolutionary union. The Sadhbhavana party and Forum, they all had their own organisations, but I’m not sure if they even had one actual worker.”

GEFONT, which is the largest federation of trade unions, has taken the lead in trying to establish an all-party trade union alliance, says Shakya, but not much has come of it. When it comes to collective bargaining with capitalists, it is important to have a single voice that bargains on behalf of all workers.

“But workers are not always represented by unions, even if there is a single union,” says Shakya. “The mindset of whole-timers regarding workers’ rights and the workers themselves is completely different. Like we as voters believe in a party and vote for them but our mindset is completely different from that of a party member.”

The larger problem goes back to the mindset engendered by the Congress--that productivity and doing business is more important than ensuring workers’ rights. Even the trade unions aren’t necessarily interested in bargaining in favour of workers but rather ensuring that Nepal does well on the doing business index and is seen as a receptive space for mobile capital in an increasingly neoliberal world.

“We never had an opposing vision to neoliberalism,” says Shakya. “In South Africa and Nigeria, there was a movement that said doing business is not a panacea, but Nepal has never had that, largely thanks to one section of the Nepali Congress.”

All of Nepali society, including the government, opposition and civil society, is complicit in this regard.

“There’s this dialectic that comes out as a function of who is in power and who is doing the challenging,” says Shakya. “When there is the right kind of challenge, we can expect something constructive, but even that balance is missing. Instead of questioning the idea of prosperity that does not cater to the everyday lives of most people, when the opposition itself starts to say we have a better formula for prosperity and governance, then the ones in power have no battle to fight; they’ve already won.”

There is a studied academic pessimism to Shakya. But this is a pessimism born out of years of fieldwork as an economic anthropologist studying Nepal and other regions when it comes to labour and the economy. There should be a challenge, she says, but she doesn’t see any.

“The real challenge should have come from young, cosmopolitan Nepalis but even they are very happy being a part of that system,” she says. “If a challenge emerges, it will come from the marginalised, not from the bourgeois middle class. The middle class is not imaginative, it’s not creative, it’s not original and it’s not passionate.”

ON THE MENU

U Cafe, Bakhundole

Oden: Rs 700

Pork momo in soup: Rs 370

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg)