Brunch with the Post

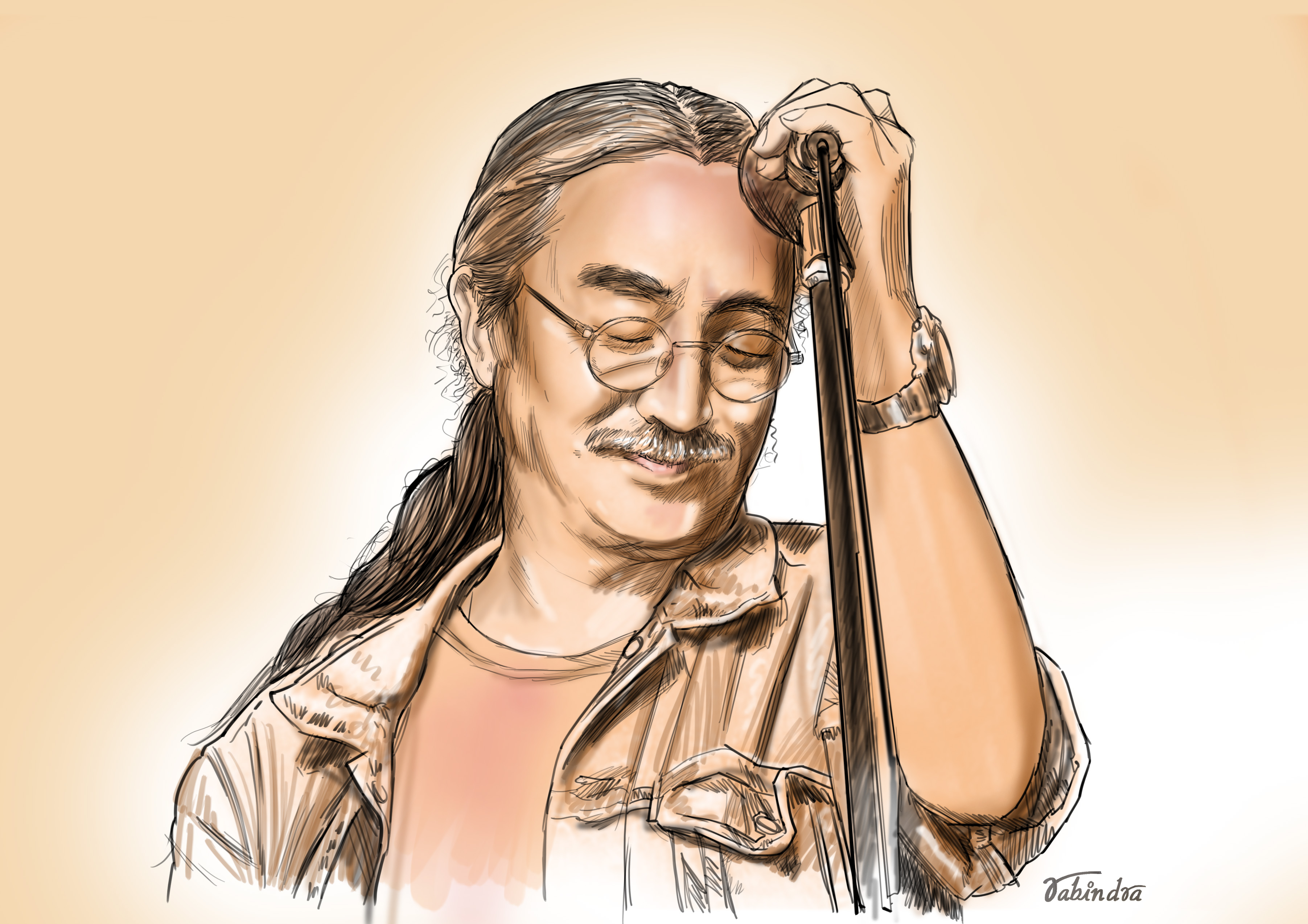

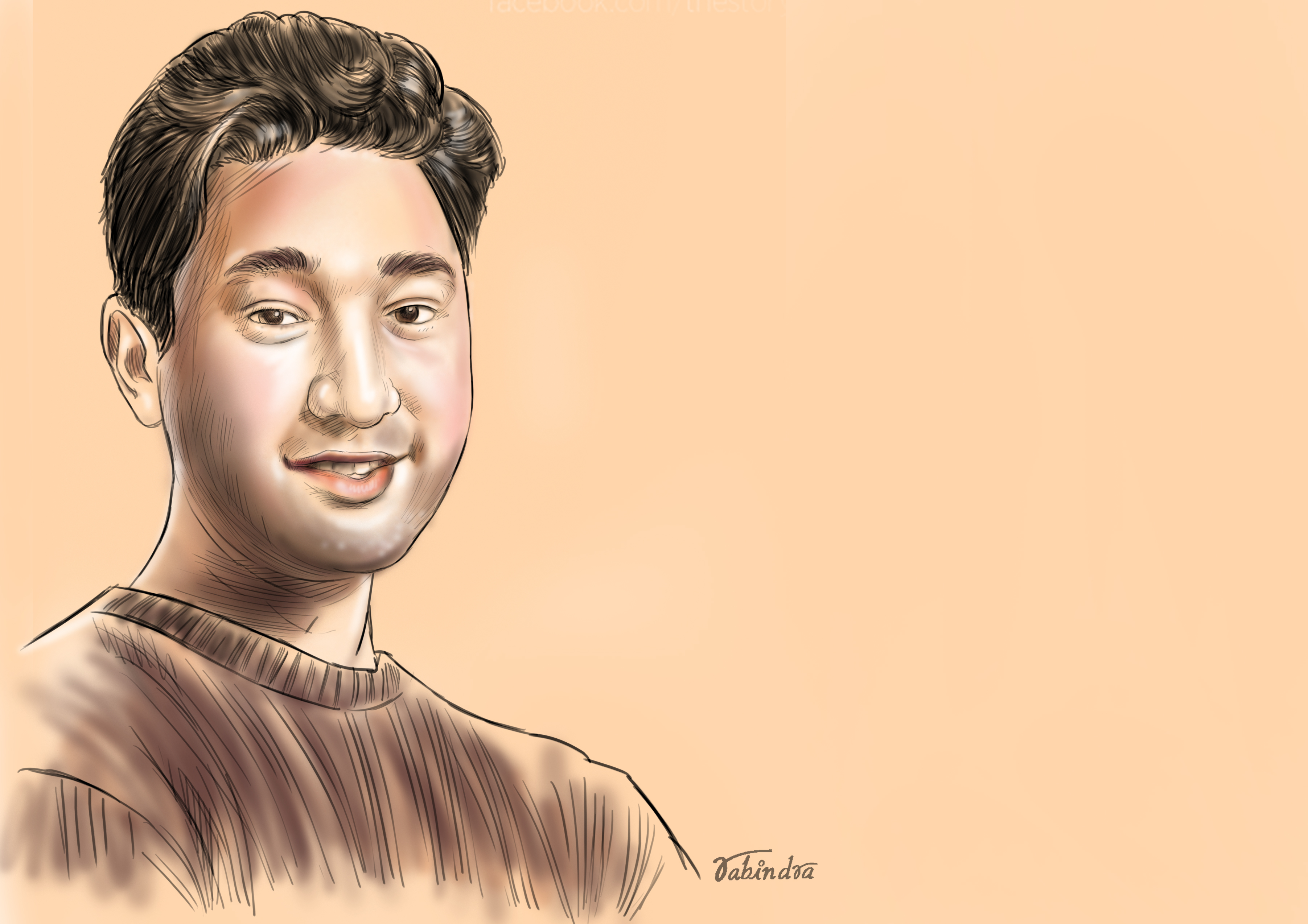

Chandra Kishore: The Madhesi agenda is a national agenda

The roving journalist talks about how corruption is becoming endemic at the grassroots and the real challenge of federalism.

Pranaya SJB Rana

We are at the Downtown Restaurant in Pulchowk and we’ve just ordered veg momos. I’ve invited the travelling journalist to discuss politics, but he says he wants to talk about something different.

“I want to talk about what is happening at the ground level,” he says.

Upendra Yadav and the Samajbadi Party have just quit government but I acquiesce. I do want to know what is going on at the ground level. But Kishore’s assessment is dire.

“What has happened since the elections is that those who won now assume they have a rightful claim over resources,” he says. “In the Madhes, you can reach everywhere on a motorcycle, but local representatives want a car, because now they are Singha Durbar.”

Corruption has become endemic, he says. It has permeated down to the local levels, so much so that villagers celebrate corruption as a path to wealth and success.

“Once corruption was limited to a few thousand people in the centre,” he says, “but it is now at the grassroots and society itself is becoming corrupt.”

Kishore lives in the border town of Birgunj but he travels widely, especially across the plains. If this argument was coming from anyone else, I might have been likely to dismiss it as hyperbolic, but Kishore is not known for exaggeration.

“We made various reforms to the electoral process, including the ballot, voting booths and even the system itself, but we haven’t talked about financing,” he says. “When even a campaign for a ward chair costs millions, candidates start to see the election like an ATM—you put in money today and you take it out tomorrow.”

But isn’t this the opposite of what was desired when the country went federal, I ask. Local governance was supposed to bring accountability and transparency. And won’t his assessment embolden critics of federalism who say that we should never have gone for federalism in the first place?

“I am not talking about federalism; I am talking about democracy,” Kishore says, smiling wanly. “A state can be democratic without being federal. The expense of elections has become a cancer and if we don’t deal with this right now, it will destroy society.”

Kishore is concerned with how federalism has been implemented. Federalism might have been well-intentioned, but it, like every other system Nepal has tried on, was coopted. It was the Madhesi people who asked for federalism, but now that it has arrived, Madhesis are no winners. They, like everyone else, remain at the mercy of a centralised state.

“The Madhes wanted provinces, but the centre was too afraid so it argued that the only way to make democracy sound was to give power to the local level,” says Kishore. “So election tickets for the local level were handed out by the political parties at the centre. What ended up happening is that the province got stuck in the middle as a body without a head or arms.”

Despite this structural mistake, Province 2 is governed by a Rastriya Janata Party and Samajbadi Party coalition. It is the only province that is wholly Madhesi in geography and the only province that the ruling Nepal Communist Party doesn’t lead. That, however, might soon change. With Samajbadi’s exit, the ruling party is now pursuing a deal with the Rastriya Janata Party, which could turn the tide in Province 2. That would give control of all provincial governments and the federal government to one party, a dangerous situation in any multi-party democracy.

“Janakpur is the only place that is raising its voice against the excesses of the centre,” says Kishore. “But Province 2 is also a government on its own and it needs to think about how federal-friendly its processes are. If we’re going to scrutinise the federal government, then we also need to scrutinise Janakpur.”

Kishore is right. There have been concerns about Janakpur, the provincial capital, and its tilt towards Hindutva brewing across the southern border. The city is sheathing itself in saffron, under the direct patronage of the city authorities.

Kishore agrees that the influence of the south is growing stronger in Janakpur but he sees it everywhere else too.

“The influence of the neighbour is all over Nepali society and unfortunately, even the progressives have abandoned the red of revolution for saffron,” he says. “Our leaders visit babas and instead of funding hospitals and schools, they build temples.”

The influence of Nepal’s neighbours is not just limited to religion. Both India’s Narendra Modi and China’s Xi Jinping are strongmen who are in the midst of attempting to stifle dissent and silence critics.

“We’re seeing this all over the world, where people who want to hollow out democracy have risen through the electoral process,” says Kishore, pointing to Modi in India, Trump in the US, Erdogan in Turkey, and Duterte in the Philippines. “These kinds of people do not come from outside with a gun; they rise from the inside and try to suppress due process with their majoritarian strength. The majority then gets to decide what is true.”

Protests are currently breaking out across India with the state violently suppressing them. Nepali liberals are in symbolic support, via social media and newspaper columns. Kishore sees a wry irony here.

“What happened during the Madhes Movement?” he says. “The state aimed for the head and killed its own citizens.”

In 2015, when the Madhes was aflame with protests over the new constitution, many of those who are condemning Modi today were in support of the government’s brutal suppression of the protests, says Kishore. Dozens of people died in the protests, shot by the state’s security forces.

“The Madhes Movement was a struggle against the state, but it was portrayed as a fight between Madhesis and Pahadis,” he says.

Another narrative that found purchase in Kathmandu was that Madhesis wanted a separate state, which Kishore vehemently denies.

“The walls in the Madhes might have said ‘Madhes sarkar’ but Madhesis were asking for a Nepali identity,” he says. “It was a community saying we are part of this country and so is our ethnic and regional identity.”

The Madhes has always been a political region. As the plains, it is easy to get around and gather, and its diversity of communities, castes, religions and languages has meant that there is always dialogue happening. The Nepali Congress, during its revolutionary days, was based in the Madhes, and in 2007, the first Madhes Movement established federalism as a national agenda.

“The Madhes is responsible for the rest of the country too,” says Kishore. “It can raise the issues of the mountains and the hills because in the Madhes, you can get a hundred people together in minutes.”

Kishore relates that he only realised this potential when he visited Manang where it takes days for villagers to even meet their local leaders, let alone gather together for a discussion.

“I used to think it was unfair that mountainous regions with sparse populations got the same MPs as regions of the Madhes with so many people,” he says. “But then I saw the geography and I realised that we have been pursuing a politics based on people but we haven’t really talked about a politics based on geography.”

Kishore believes that the Madhes agenda is always a national agenda, because at the heart of Madhesi demands are a clamour call for recognition and representation--for all castes, ethnicities and regions.

The large political parties have failed to understand this and the regional parties have attempted to instrumentalise this. This is evident in the ways in which each Madhesi party has attempted to court the ruling party and get into government. But it is also apparent in a much more symbolic manner.

“They’ve all removed Madhes from their names,” says Kishore.

Kishore has talked for long, and we have finished our momos. He asks for two cups of black tea and wants to talk about “dukha-sukha”. He is an amiable and earnest man. I ask him about his plans, and he says that he will soon be on the road again. But there is something pressing that he wants to mention, and it has nothing--and everything--to do with politics.

“We’ve turned all our villages into municipalities,” he says. “We’re attempting to turn villages into cities and cities into villages.”

People from the villages are migrating to the cities in droves but the city is also entering the village, in the forms of roads, infrastructure and an urban mentality.

“Villages were spaces where everyone knew everyone else,” says Kishore. “There were chautaris and in the winter, ghurs--open fires that were platforms for dialogue and discussion. But an urban mindset has now permeated the villages. No one knows anything about their neighbours.”

Being ‘rural’ is a way of life, he says, not a level of development.

Villages once used to produce vegetables and fruits that it would send to the cities. But now, villages have become markets for cities to dispatch their noodles and biscuits to. The real challenge for local bodies and for federalism is to preserve the local, indigenous way of life.

“Local bodies need to think about increasing production and maintaining a community that is in harmony with nature,” he says. “Villages don’t need the same kinds of roads as in the cities. But they do need their trees, ponds and rivers.”

On the menu

Downtown Restaurant, Pulchowk

Veg momo: Rs 150

Coffee X2: Rs 150

Black tea X2: Rs 110

14.99°C Kathmandu

14.99°C Kathmandu

.jpg)