Brunch with the Post

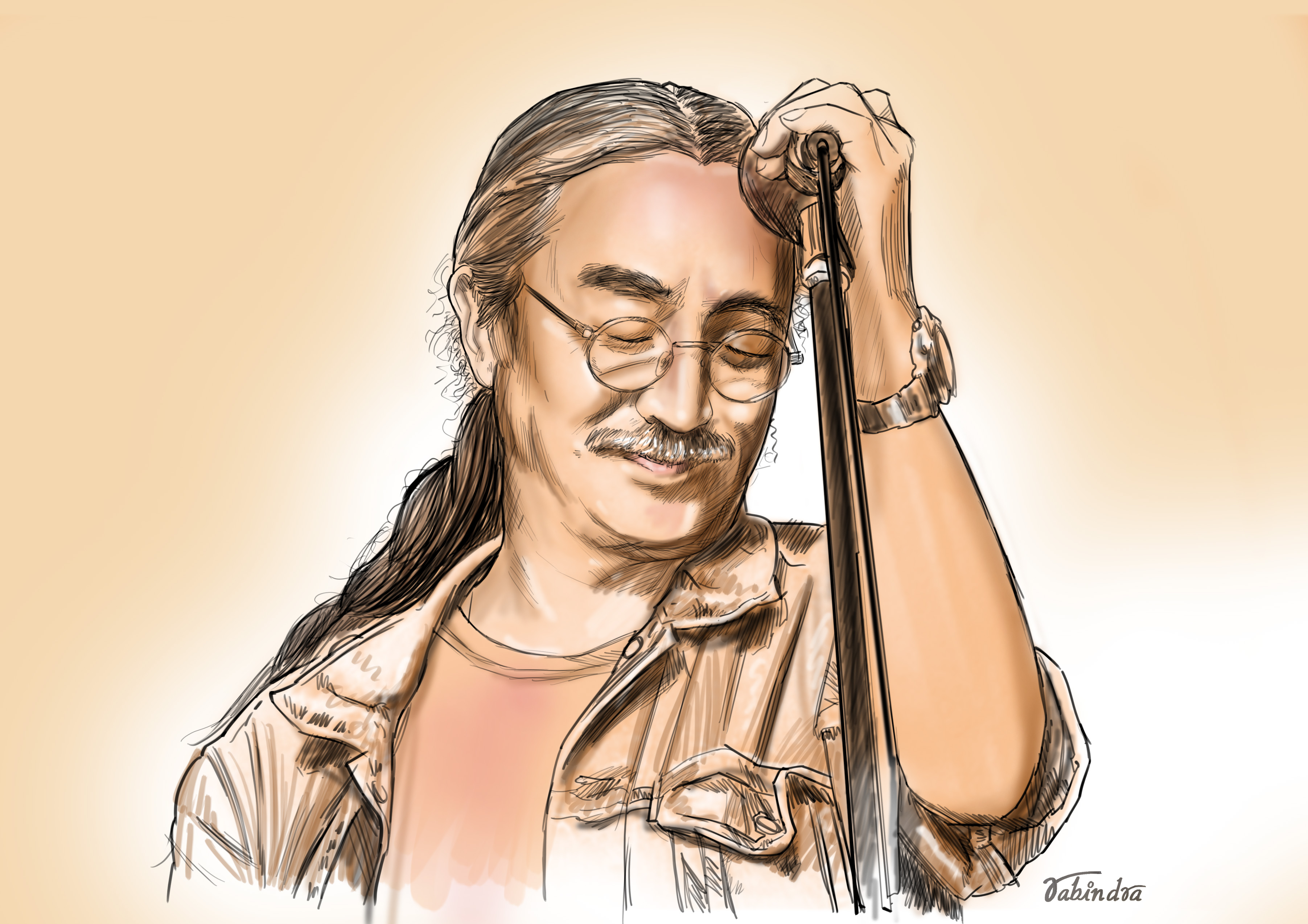

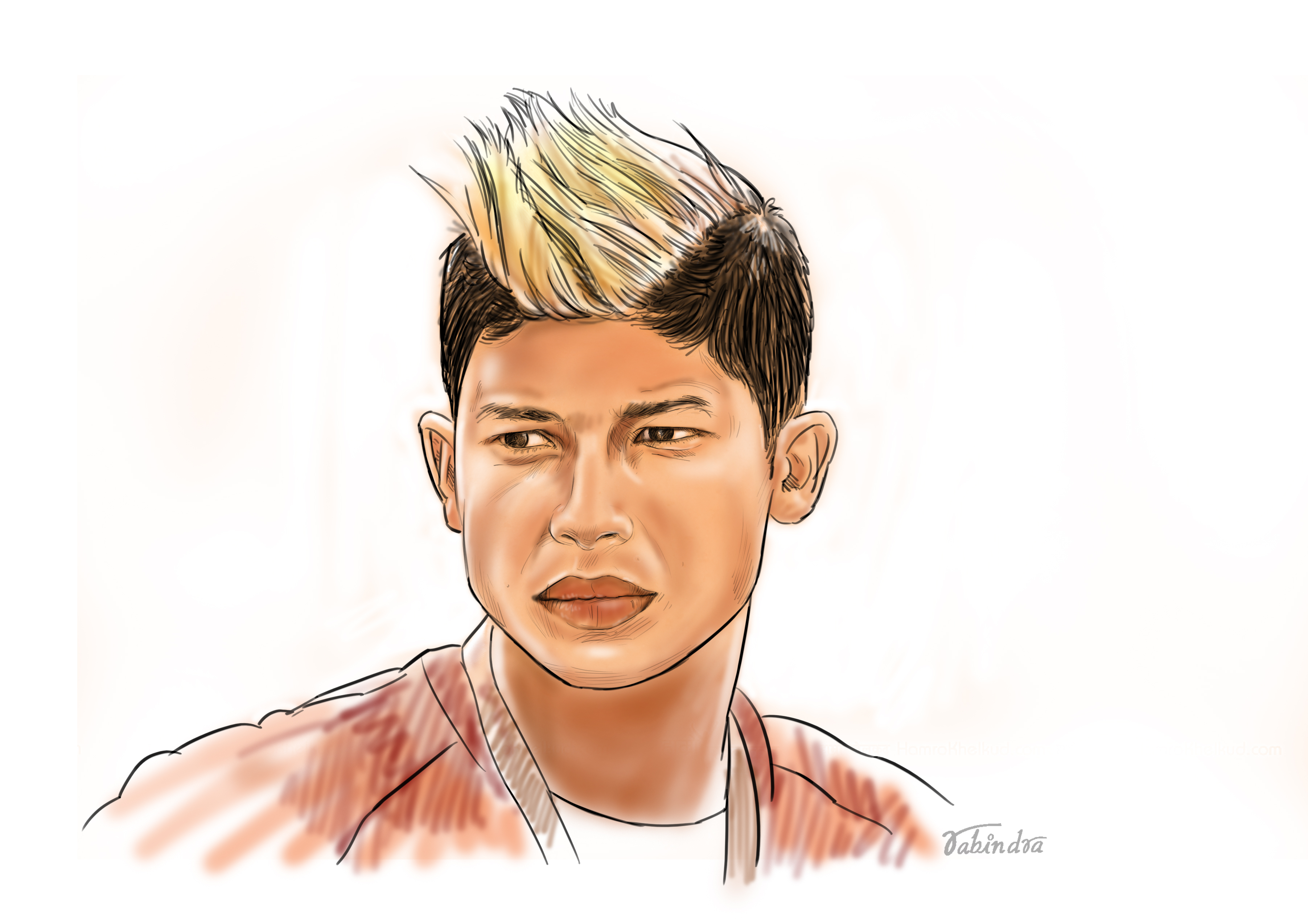

Kiran Manandhar: Artists are the heart of a country

The veteran artist speaks about his eventful journey into becoming one of Nepal’s finest painters and his gripe with the state of art in the country.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Kiran Manandhar and I keep missing each other. We’d planned to meet at Jimbu Thakali in Tangal but a series of misunderstandings have meant that Manandhar has visited at least two other thakali places before finally arriving at Jimbu.

Underneath his jacket, he’s clad in his trademark daura-suruwal and he is raring to take a fork to Jimbu’s famed food. We sit down, order ourselves thakali sets--chicken for him, veg for me--and begin our conversation.

“I love food,” says Manandhar. “I love to eat and I love to cook. Both painting and cooking make me feel the same--adding all the ingredients into a dish is like mixing colours.”

Manandhar is one of Nepal’s preeminent artists, one of the first to embrace the free-flowing, rapturous technique of abstract expressionism. Manandhar’s paintings are riots of colour against the silhouettes of bodies and landscapes. He’s been painting for decades now and has exhibited widely in Nepal and abroad, especially in France and Germany.

We begin, naturally, by talking about art. He travels frequently between Nepal and France, where he paints, exhibits and even teaches art. I ask him how he got his start as an artist and he tells me a tale that combines youthful rebellion and a passion for the arts with plain old obstinacy.

“My father was a mechanic and he wanted me to become an engineer,” he says. “He hated that I was interested in painting. He forbade me from doing any kind of art and made sure I didn’t have access to any paint or even blank paper.”

But Manandhar was an enterprising kid and he found ways. In school, he’d borrow paper and paints from his classmates. If they were willing to share then all was well but if they did not, Manandhar had no qualms about getting into a fight and taking their supplies, he says with a laugh.

“I hated studying; I didn’t like letters and words,” he says. “So instead of school, I would go to the banks of the Bishnumati river where I would sit and make sand sculptures. I would also go to the Nagarjuna forest where I would hide the few paintings and artwork I made in the trees because I couldn’t take them home.”

It was while he was playing in the sand and making sculptures that a tall man came over to see what he was doing.

“This man looked at what I was making and remarked that I was a good artist,” says Manandhar. “He gave me a card and told me to come visit him.”

That man turned out to be Chandra Man Singh Maskey, a pioneer of Nepali art and one of the first Nepalis to study art academically. Manandhar’s father was surprisingly elated about this chance meeting with Maskey because coincidentally, Maskey had taught him English. So while everyone assumed that Manandhar was learning English, Manandhar himself assumed he was going to learn about art.

“But for the first two or three weeks, all Maskey asked me to do was go out and buy fruits and vegetables,” says Manandhar. “I kept expecting him to teach me art but all I was doing was buying groceries.”

It didn’t take long for Manandhar to get frustrated. When Maskey came in one day, Manandhar told him that he was going to quit, as he didn’t want to become an errand boy anymore.

“Maskey then told me that he had thought I was going to become an artist but he was not so sure anymore,” says Manandhar. “You don’t have the eye, the hands or the heart.”

In Zen master fashion, Maskey had been testing Manandhar. The fruits and vegetables were a gauge of Manandhar’s sensibilities.

“I grabbed the saag without looking to see if it was green. I picked fruit without squeezing it to see if it was ripe. And my heart was never in what I was doing,” recalls Manandhar. “I finally understood what he was trying to teach me.”

Manandhar begged to stay and Maskey relented, teaching him about landscapes, portraits and still life. But eventually, Maskey handed him off to another man, Ramananda Joshi, another pioneer of Nepali art and the man behind Park Gallery.

Under Joshi, Manandhar primarily studied oil painting, but again, it was all done surreptitiously, lest his father found out. But his introduction to modern art and abstraction would come at the hands of another, the Indian art critic and painter Ram Chandra Shukla.

After asking for more karela with his dal-bhat, Manandhar recalls how he first met Shukla.

“Shukla had an exhibition in Kathmandu and I had gone to look at the paintings. I didn’t understand any of them, so being the kind of kid that I was, I turned the paintings around so they faced the wall,” he says. “Shukla came in and asked who had done this. I told him that it was me. He then asked me if I understood the back of the painting. I said I did, because it was canvas. He appreciated that.”

After impressing Shukla with his rambunctiousness, Manandhar was invited to come to Benaras to study painting. Manandhar took Shukla up on the offer but told his father that he was going to study engineering. Even in Benaras, Manandhar relates the numerous times he got into trouble. One instance left him tied to a pole because he had attacked the college seniors who were trying to ‘rag’ on him.

Eventually, his father found out the truth and cut him off. With nowhere to go, Manandhar ended up in the railway station, dodging policemen and living off of the kindness of strangers.

“I lived in the station for three months, drawing on newspapers because I didn’t have access to any paper,” he says. “But I don’t regret any of it. My three biggest teachers were the Nagarjun forest, the banks of the Bishnumati and the railway station in Benaras.”

The head of the arts department at his university eventually took pity on him and he managed to get a place to live in and finish his studies. He came back to Kathmandu but there was nothing for him to do. He didn’t want to get into government service and he didn’t want to become an art teacher. So, he decided to open up his own art gallery--Palpasa Gallery, which doesn’t exist anymore.

Over the years, he painted, built the gallery, and did exhibitions. But it was only in the early 80s, when he got a chance to travel to Europe for the first time, that he realised what it means for a country to celebrate art and artists. In Germany and France, he saw how artists were supported not just by the state but also by its citizens. Artists got living allowances from the government but businesses patronised their art. In parts of France, restaurants even offered artists a discounted price.

Even if Nepal and Nepalis did not do any of this, the least that the country needed was a fine arts academy, he thought. And so, during every major people’s movement, while politicians were demanding changes to the system, Manandhar was right there alongside them, demanding a fine arts academy. It took a long time for his dream to finally come to fruition. It was only in 2010 that the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts was established, with Manandhar as its chancellor.

“We finally have an academy but it turns out, we still don’t have people who are actually willing to do the work that is required,” says Manandhar.

Manandhar had big plans for the academy. He wanted to create a studio and residency space for artists and he wanted to open up a museum of contemporary art within the academy’s premises. None of that happened. Instead, the government attempted to sell off part of the academy’s premises to private land developers.

“I told them that I would stand at the gate and if they wanted to take the land then they’d have to run me down,” says Manandhar. “But once I left, 15 ropanis of land were sold.”

Manandhar quit as chancellor to make way for someone else but in hindsight, he believes it was a mistake to leave.

“I am founder-chancellor of the academy but I was recently forced to scold the people there,” he says. “They’ve ruined the place. The place is now just filled with party members.”

Manandhar says all of this without malice, but it is clear that he is disappointed. We’ve finished our dal-bhat and over coffee, I ask him about two things that are supposedly his obsessions--women and noses.

“I love women,” he says wistfully. “I like beauty. I don’t actually know how to draw men.”

He then goes off about one of his past girlfriends, a girl from a minor royal family. But I press him on the nose.

“It’s not just the nose,” he says, taking a piece of paper and deftly drawing the profile of a woman. “It’s the entire silhouette where the eyes are inspired by fish and fish are lively, just like the eyes of a woman.”

Manandhar has had a long and storied career and he’s established a reputation as a mentor to the younger generation. He takes an active interest in the work of younger artists and regularly provides constructive criticism. But that’s something everyone needs to do if Nepali art is to flourish, he says.

“The old artists need respect but it’s the new ones who will take things forward,” says Manandhar. “But they need support. People build big houses but don’t think of buying some art to hang on the walls.”

Support needs to also come from the government, but Manandhar is not so certain that those in power have ever really understood what art is.

“The government likes to call artists ‘desh ko gahana’,” he says, “but artists are not ornaments; they are the heart of a country.”

ON THE MENU

Jimbu Thakali, Tangal

Hot lemon with honey: Rs 115

Americano X2: 265

Chicken thali: Rs 438

Veg thali: Rs 384

Cappuccino: Rs 141

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg)