Brunch with the Post

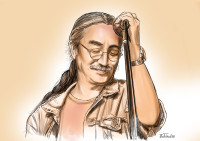

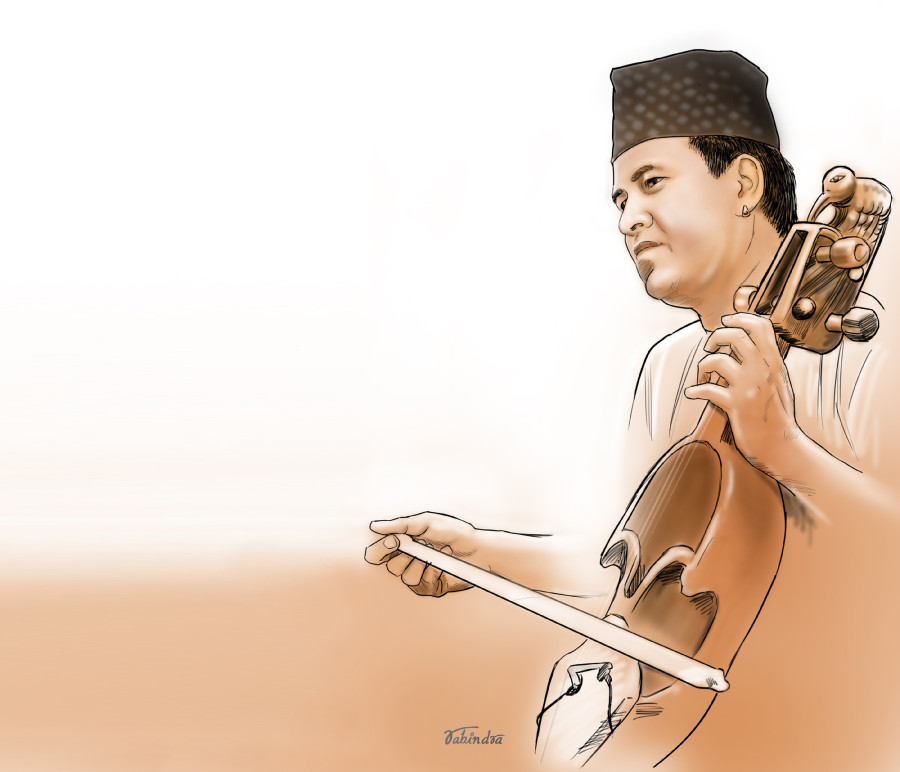

Shyam Nepali: The sarangi has no limitations

The musician talks about the gandarbha tradition and his work to preserve the musical legacy of the sarangi.

Pranaya SJB Rana

To an untrained ear, the strains of the sarangi are plaintive. Every note sounds like a cry and no matter how joyful the song, the sarangi appears to add a hint of melancholy, as if to compensate.

Shyam Nepali disagrees with the assessment.

“The sarangi in Man Magan is not sad,” he says. “It is not just a sad instrument. The sarangi has no limitation, it has no genre. It can merge with any musical style and any other instrument.”

Nepali knows what he is talking about. After all, he has been playing the sarangi for over 30 years now, raised in the gandarbha tradition. In addition to the traditional ‘gaine geet’ that the sarangi is most closely identified with, he has played pop, rock, blues and jazz. He’s even played alongside a DJ.

Nepali is one of the country’s most well-known sarangi maestros. He’s played in a number of bands, including the fusion outfit Trikaal and the classical troupe Sukarma. He’s travelled the world, playing cultural shows and showcasing what is perhaps Nepal’s most iconic instrument, whose sound has come to become synonymous with the country.

When we meet at the Mauri restaurant in Lainchaur, he arrives carrying the sarangi on his back. It’s almost as if he never leaves home without it.

“I come from a family of musicians so I always had the privilege of being surrounded by music while growing up,” he says, as we sit down to talk over pizza.

Nepali’s father is Ramsharan Nepali, a celebrated musician in his own right, and his grandfather is Magar Gaine Gandarbha, who often played for the royal family. Coming from a family of gandarbhas, it was only natural that Nepali too would pick up the instrument. And he did, at the age of 5.

“Gandarbhas are not just musicians; we are storytellers,” he says. “My grandfather would go around from place to place, collecting news and turning them into songs.”

Gandarbhas were itinerant musicians, providing both information and entertainment across Nepal’s difficult terrain. When reading and information was the province of the wealthy and privileged, gandarbhas provided an equalising service. But with the changing times, the role of gandarbhas has changed too, and Nepali fears that Nepal might be losing something intangible.

“Everyone has a speaker in their house these days,” he says. “Anyone can make music in their own room.”

Music has become commercialised, according to Nepali. Musical concerts, he says, pay more for the sound system than they do to the artists.

“We need to take ownership of our folk music,” says Nepali. “If we play the same sarangi in a jazz song, then people celebrate it but if we play it in its original format, people say, ‘oh that’s just gandarbha music’. But folk music tells us a lot about our history, our culture and our traditions.”

But there is a small renaissance of sorts happening with Nepali folk music and traditional instruments. Bands like Kutumba and Night have carved out a niche for themselves with music that harkens back to traditional Nepali melodies using traditional Nepali instruments. There is also more of an interest among young Nepalis to pick up instruments like the sarangi, as is evident in the number of new bands that have a sarangi player and the proliferation of sarangi covers on YouTube.

“There is interest among young people,” admits Nepali, “but it’s also about sensibility.

I don’t think we have confidence in our own arts and culture.”

And Nepali blames the government for that.

“The government has never attempted to promote our arts and culture as something we should be proud of,” he says. “Despite having Nepali music in every programme, music has never been treated as something to protect and preserve.”

And so, it has largely been Nepali individuals, along with foreign governments, institutions and academics, who’ve filled the void. Nepali relates an instance when he went to play a concert in Paris in the 90s.

“We were playing traditional Nepali music at the Louvre,” he recalls. “After the performance, a man came up to me and told me he had some recordings of traditional Nepali music that he wanted to play for me. When I agreed, he played a song and I recognised it—it was my grandfather playing the sarangi.”

Nepali now plans to bring those recordings back and archive them because they don’t exist in Nepal.

He has been doing his part too. He’s played all over the world, from France and the United States to Switzerland and Japan. Currently based in Boston, he’s also part of a musical course at Harvard University that teaches Nepali music and the gandarbha lifestyle.

“The city of Boston conducts musical programmes with immigrants,” he says. “They understand that immigrants don’t just bring themselves to America but also traditions and cultures. It is exciting to see people realise the value of different kinds of cultures.”

In Boston, Nepali has started a school called the Himalayan Culture Academy that teaches young Nepali-Americans about their culture through music and dance. In Nepal, he’s opened up the Sarangi Gharana in Kirtipur for research and preservation works. But he believes that teaching music should become more institutionalised, and in a way in which musicians too can benefit.

“There are some efforts aimed at teaching folk music, like Project Sarangi and a few music courses in universities,” he says. “But I think it should happen more aggressively. Old masters should be employed by these universities so that students can learn from them but they can also make a living for themselves.”

Sarangi Gharana also makes sarangis, one of which Nepali plays himself. He thinks that the sarangi could become a premier musical instrument, like the violin or piano.

“It’s a unique musical instrument that has a lot of appeal to people around the world,” he says. “It could be marketed and sold as a special instrument from Nepal that can either be played or put up as a decorative piece. That would not just help our culture but also our economy.”

But like with most people I’ve spoken to for this column, he doesn’t expect much from the government.

“I don’t think that they understand the value of Nepali music,” he says. “Nepali music is more than just lok-dohori.”

Music is like an ocean, Nepali tells me. You can go as deep as you want into it and you might never reach the bottom.

“Music is not just for the ear,” he says. “It’s also for the soul.”

ON THE MENU

Mauri Restaurant, Lainchour

Americano X2: Rs 371

Mushroom pizza: Rs 619

18.37°C Kathmandu

18.37°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)