Miscellaneous

Truth to populist power

Once upon a time, we had the political generation that sought to stabilize and democratize Nepal by bringing down the Rana regime. Subsequent generations have had it easy, and gone soft when it comes to protecting pluralism and representational politics.

Kanak Mani Dixit

Once upon a time, we had the political generation that sought to stabilize and democratize Nepal by bringing down the Rana regime. Subsequent generations have had it easy, and gone soft when it comes to protecting pluralism and representational politics. Much of the positive change of the modern era was due to the sagacity of the population at large, and the so-called civil society stalwarts did not so much lead as follow.

Once upon a time, we had the political generation that sought to stabilize and democratize Nepal by bringing down the Rana regime. Subsequent generations have had it easy, and gone soft when it comes to protecting pluralism and representational politics. Much of the positive change of the modern era was due to the sagacity of the population at large, and the so-called civil society stalwarts did not so much lead as follow.

During the 30 years of the Panchayat regime, from 1960 till 1990, servility overtook the polity, sanding down dissidence and promoting vehement anti-intellectualism. The result was a lack of clarity and courage on the part of civil society, and the Panchayat legacy lives on today, also because the ‘stalwarts’ are products of that era.

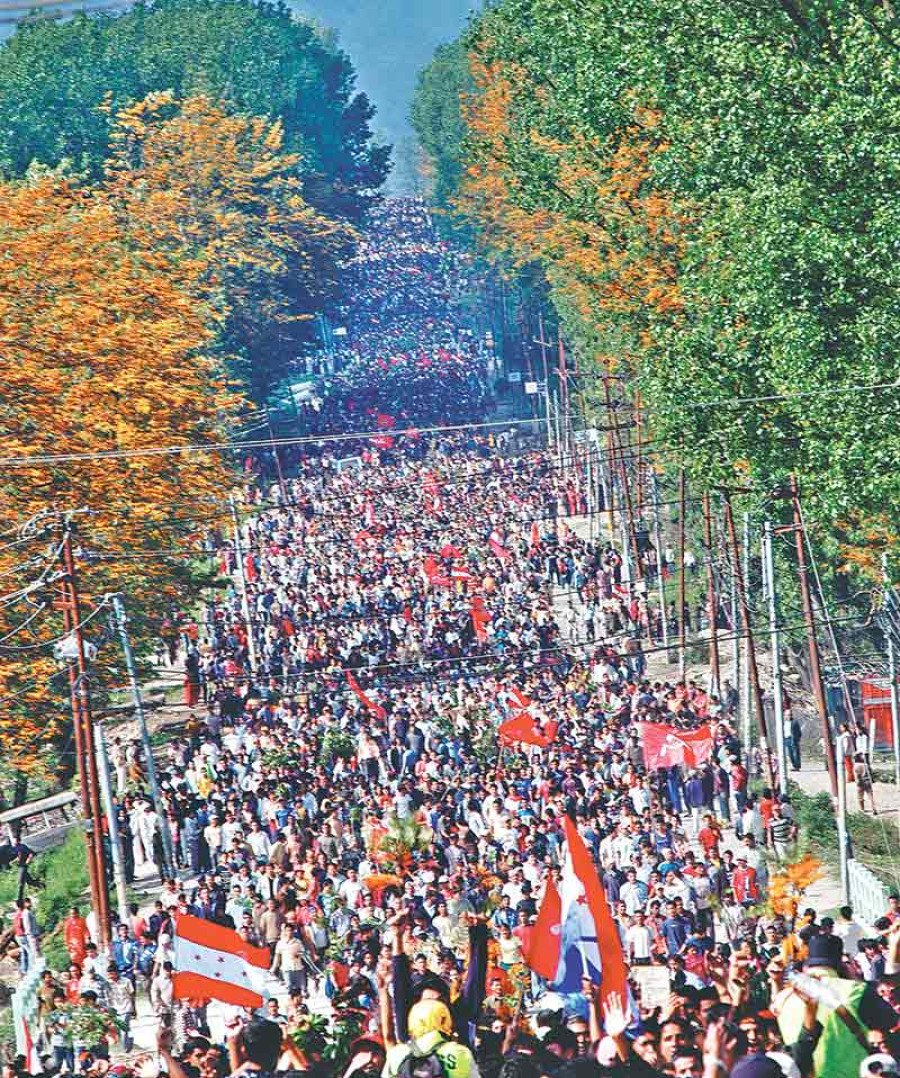

I myself am a child of that era, having gone to school and college in the Valley in the ‘60s and ‘70s, breathing the same air as others, where questions were not asked and privileges protected. Propelled along by the People’s Movement of 1990, we did get back to democracy, but did little to protect and develop it thereafter. The rise of multi-party democracy under the Constitution adopted that November released the forces of social and economic transformation, made possible by the proclamation of the fundamental freedoms.

As others have said, democracy came too easy so the intelligentsia did not appreciate enough what had been achieved. Before the new democracy (with constitutional monarchy) was able to strike root, the Maoists were already off on their horrific journey. From that point in 1996 till today, Kathmandu’s civil society has not been able to exhibit the sense of self required to fight the contagion of the modern era—radical populism. We had learnt by rote that democracy was about fighting authoritarians and dictators, and appreciated little the socio-political devastation that could be wrought by populism of the radical kind.

It was easy enough to challenge Gyanendra when he sought a reversal to the Panchayat in 2005, but that was a black-and-white fight not requiring second thought. The intellectual elite preferred not to address the greys, to distinguish between Maoist rhetoric and the dangers of its implementation, for example, or how to welcome the Maoists into above-ground politics without ever accepting that there had been a need for a ‘people’s war’.

The civil society stalwarts were thus un-equipped to tackle radical populism, while the academics, political consultants, and the leadership of NGOs/INGOs preferred to go the way of the donors. The ‘birds of passage’ (bilateral donor agency heads who come and go) went a distance setting the constitutional and peace discourse, compromising large swathes of the intelligentsia.

Inconvenient truths

This civic weakening accelerated with the rise of the Maoist ‘war’. The opinion-makers preferred to look away, hoping that the insurgency would be tackled by the state, and when the movement expanded, the most the great commentators cared to do was offer the airy opinion that the rise of Maoism was “the result of poverty.” Had there been a more robust rejection of ‘armed revolution’, the rebels would not have got as much traction and the society would have reverted to the brick-by-brick building of representative, parliamentary democracy started in 1990.

By the time the Maoists landed feet first in open society in 2006, the stalwarts were completely in awe of these ‘revolutionaries’. When the United Nations Mission to Nepal (UNMIN) in its wisdom privileged the Maoists and humiliated the democratic parties, they joined the bandwagon. Despite having participated in the People’s Movement of 2006, many of the stalwarts ended up denigrating it by accepting the ultra-progressive suggestion that the Maoists were the Movement’s vanguard. This gave energy to the Maoists as Baburam Bhattarai sought to push through a North Korea-like constitution during the first Constituent Assembly.

The donor largesse that arrived with conflict prevention, peace-building and post-conflict rehabilitation tended to be diversionary. Even today, amid the self-congratulatory applause of the donors and stalwarts alike, few want to be disturbed by talk about the child soldiers, or the discarded women commanders, or the misery of the victims of conflict, or accountability for war crimes and crimes against humanity of both sides. Nanda Prasad Adhikari died in hunger strike on 22 September 2014, demanding justice for the murder of his son by Maoists, but the celebrities of civil society want to hear none of it. Nor do they want reminding of the Doramba massacre, Maadi bus blast or the killing of the Dhanusha Five.

Such was the self-absorption of these civil society celebrities that there was even a proclivity among some of them to wish a collapse of the political process, so that they could actually take the non-representational route to executive power. These egotistical individuals were not a little miffed when this did happen, but Supreme Court CJ Khil Raj Regmi pipped them to the post in March 2013.

Over the last decade, the Maoist propaganda, also propagated by the ultra-progressives, was able to capture the imagination of the intelligentsia and international community. The preferred trope was that the ‘people’s war’ was started against the royal regime, forgetting that Nepal in 1996 was a democratic state. The destruction of the economy, the polarisation of communities, and fact that in total the country lost two decades of socio-economic advancement due to the conflict and its aftermath are simply inconvenient truths. In the claim that federalism, republicanism, secularism as the successes made possible by the ‘people’s war’, there is a deliberate willingness to forget what all two decades of multiparty democracy may have achieved, work that was already begun in the early 1990s.

Armchair ultras

If one had hoped that the younger members of academia/civil society—particularly the well-educated scions of the Panchayat era elites—would stand up for democracy, human rights and pluralism, that expectation was rudely belied. Instead, this English-savvy cohort made merry with the donor largesse that landed on their lap without the asking. Some amount of undergraduate-level political romanticism also helped this category to lionise the Maoists, denigrate the democratic parties and on the whole (with the facility of their pen) misrepresent the Nepali experience to the world.

Far be it for the English-speaking armchair ultras to challenge Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Baburam Bhattarai on the devastation the two had introduced. The historical inequities and marginalisations of Nepal are presented without context, forgetting the fact that Nepal represents a society striving to improve throughout the modern era. The 1990 Constitution which made all the transformations thereafter possible has been made subject of all-out disparagement, whereas its contribution can and must be used to improve implementation of the Constitution of 2015.

The stalwarts and the consultant-activists could be called obstructionists during the the constitution-writing, for they were partly responsible for the sankramankaal (transition period) extending so tenuously for a full decade. They preferred to troll the surface of the discourse, siding with the Maoist-friendly narrative rather than speak their views on the numerous issues that suddenly required resolution.

They were not available when inter-community relations plummeted, particularly on the Madhes-Pahad front. They hewed close to the lowest common denominator when it came to having a position on secularism, federal structuring, inter-community relations or foreign interventionism. If anything, this cohort would take cover when sharp positioning was required, by not taking a stand at all, or taking a stand only once it was safe to do so.

Most recently, you saw this attitude in relation to the Indian blockade of 2015, the rise of Lokman Singh Karki as head of the CIAA, and the impeachment proceedings against CJ Sushila Karki. There was the resounding silence of years when it came to local government elections, needed both for the sake of representational politics at the grassroots as well as the path to implement the new Constitution. You saw it earlier in the attempts to sabotage the Constitution writing, and later in helping those who did not want the Constitution implemented. (Easy enough in these days of social media to go to the archives to see the positions held, or the meaningful silence, of well-known opinion makers during the critical moments of the recent past...)

Thankfully, the constitutional process did not fall to sabotage and the country has got itself the new Constitution. The urgency now is to work for the adoption of hundreds of laws required under the Constitution, which will require a base-level understanding between the Nepali Congress and the CPN (UML), most importantly. This understanding will also help in carefully identifying weaknesses in the Constitution and improving it through amendments.

Governments led by political parties are only as good as the civil society that watchdogs them. Civil society of the last two decades did not, as a whole, live up to the stringent requirements of democracy, human rights and social justice. The challenges of implementing the Constitution amid existing political and social conditions are daunting, and the hope is that the flotsam of old will be swept away and the polity and people will get the kind of civil society they deserve, rising up in the seven provinces to reflect new realities and new hopes.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu