Miscellaneous

The royal roots of Central Zoo

The story of how Juddha Shumsher’s zoological garden was born and evolved.

Prawash Gautam

What animals did Juddha Shumsher have in his zoo?

“We only have records of animals from the mid-1960s,” says Ganesh Koirala, who has been employed at the Central Zoo for the past 36 years and currently serves as its information officer and programme officer. “That too I hand-copied from an old torn-down file that I came across.”

Today, the Central Zoo, which sprawls across six hectares in Jawalakhel, Lalitpur, houses as many as 1,298 wild animals of different species of mammals, reptiles, fishes and birds from Nepal and around the world—from tiger, rhinoceros, hippopotamus and red panda to its recent attraction: a pair of chimpanzees.

After enduring decades of neglect under various government bodies, with its animals and infrastructure scraping along in a deplorable state, the zoo received a new lease of life with improved infrastructure and animal care in 1995, when it came under the management of the King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation (KMTNC), now known as the National Trust for Nature Conservation, in 1995.

Today, the Central Zoo is an entertainment venue, one of the most happening places in the Kathmandu valley. Flocked by thousands of daily visitors, the zoo now also hosts rescued animals and those in need of rehabilitation. It is also a site for conservation education.

But when Juddha Shumsher Rana (prime minister from 1932–1945) built the Jawalakhel Zoological Garden on the premises of his Jawalakhel Durbar (where Nepal Administrative Staff College stands today) in 1932, he did so purely for private interests—as a space of entertainment and amusement for him and his family.

Built in the semi-wilderness of Jawalakhel around a historical pond dating to the 17th century during the reign of King Siddhi Narsingh Malla, the zoo also became the space he could use to show his respect for two women he revered, his mother and sister-in-law, and indulge in one of his favourite pastimes—gambling.

Today, the Central Zoo, nestled in the heart of Jawalakhel's sprawling crowd, does not go unnoticed, and its story is well told. But what passions drove Juddha to build the zoo? What was its original layout? What animals did it have in the beginning? And how did Juddha spend time there?

“I remember once seeing a small board that read ‘Jawalakhel Zoological Garden’,” Koirala says. “I don’t know whether it was from Juddha’s time or was made in the later years. It must surely be that Juddha built the zoo out of influence from the British given how this term was used by them.”

Koirala adds, “There is a former employee, now an elderly gentleman who worked in the zoo in the 1960s. He surely has some stories from Juddha’s time.”

Birds, beasts and palaces

To trace the birth of Jawalakhel Zoological Garden, one has to look at the history of Nepal’s rulers owning birds and animals.

Like rulers around the world, Nepal’s royalty kept wild and exotic birds and animals in captivity as a source of pleasure and mark of wealth and power. The book ‘Social History of Nepal’ by historians TR Vaidya, Tri Ratna Manandhar and Shankar Lal Joshi details how Mallas during the mediaeval Kathmandu Valley to Ranas and Shahs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries owned rare, exotic creatures.

In 1708, a rhinoceros in Kathmandu Valley broke the iron chain in which it was bound and killed its tamer. In 1714, Bhaktapur’s King Bhupatindra Malla gifted a camel and an elephant to Kantipur’s King Bhaskar Malla to build peace.

Among Shahs, King Rana Bahadur Shah in particular was reputed for his collection of birds and animals. He also owned a zoo outside his palace in Basantapur Durbar Square, where the Nepal Bank Limited stands in New Road today. The zoo contained “tiger, bear, monkey, elephant, horse, deer… heron, peacock… pigeon, wild dogs, rabbits, rats, mongoose.”

Jung Bahadur Rana’s zoo on the premises of his Thapathali Durbar hosted a variety of birds and animals collected during his hunting expeditions as well as those brought from abroad. Jung Bahadur himself used to “supervise and inspect it”.

Juddha Shumsher likewise had his own collection of creatures which steadily expanded into a zoological garden.

Seeking wilderness in his Jawalakhel Durbar

Juddha’s biographer Ishwari Prasad writes in ‘The Life and Times of Maharaja Juddha Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana’ that between 1933 and 1940, Juddha shot 433 tigers, 33 rhinoceros and 93 leopards. An insatiable big-game hunter, Juddha had a deep fondness for being in the wild and among wild animals, and from this came, according to oral history prevalent among members of Kathmandu’s Rana community including Juddha’s descendants, the desire to own a zoo.

Built in 1752, Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna, the world’s first modern zoo, was already over 100 years old when Juddha was born in 1875. London Zoo opened in 1828 and Alipore Zoological Garden (Kolkata Zoo) in 1875. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah Zoological Garden (Lucknow Zoo) was established in 1921. Juddha’s inspiration, his descendants say, was most likely reinforced by his tours to zoological gardens during his visits to England in 1908 and to different Indian cities.

An article titled ‘Central zoo in state of neglect’ published in The Kathmandu Post in 1996 says that Juddha one day “received a pair of leopards as a gift”, cementing his desire to own a zoo. A report ‘Central Zoo Master Plan’ prepared by the KMTNC in 1996 says that Juddha decided to build a zoo in an epiphany when he saw that some animals “including deer, a few rhinos, and some tigers had been collected from the Tarai and kept in Kathmandu” could be put into one compound in the “lonely piece of land with a large 16th [sic] century Malla period Pokhari”.

The pond lay still and serene surrounded by green wilderness ever since Patan’s King Siddhi Narsingh Malla built it in the 1600s. On the grounds surrounding this pond, the Newars from Na:Tole, Pulchowk and surroundings had their devisthans where, for centuries, they gathered to perform their religious ceremonies during Basanta Panchami and Bhoto Jatra even after this area fell within the Jawalakhel Durbar.

For the palace, the ground served as its extended garden along with a horse and elephant stable. Subodh Rana, 69, grandson of Juddha Shumsher, recalled his father Kiran Shumsher telling him that Juddha and his family sometimes also used the scenic grounds for picnics. If there was any spot where Juddha wanted to build a menagerie, it would be around this Pokhari (pond). One day, he called his grandson General Maheshwar Shumsher Rana and deputed him to the task of doing just this.

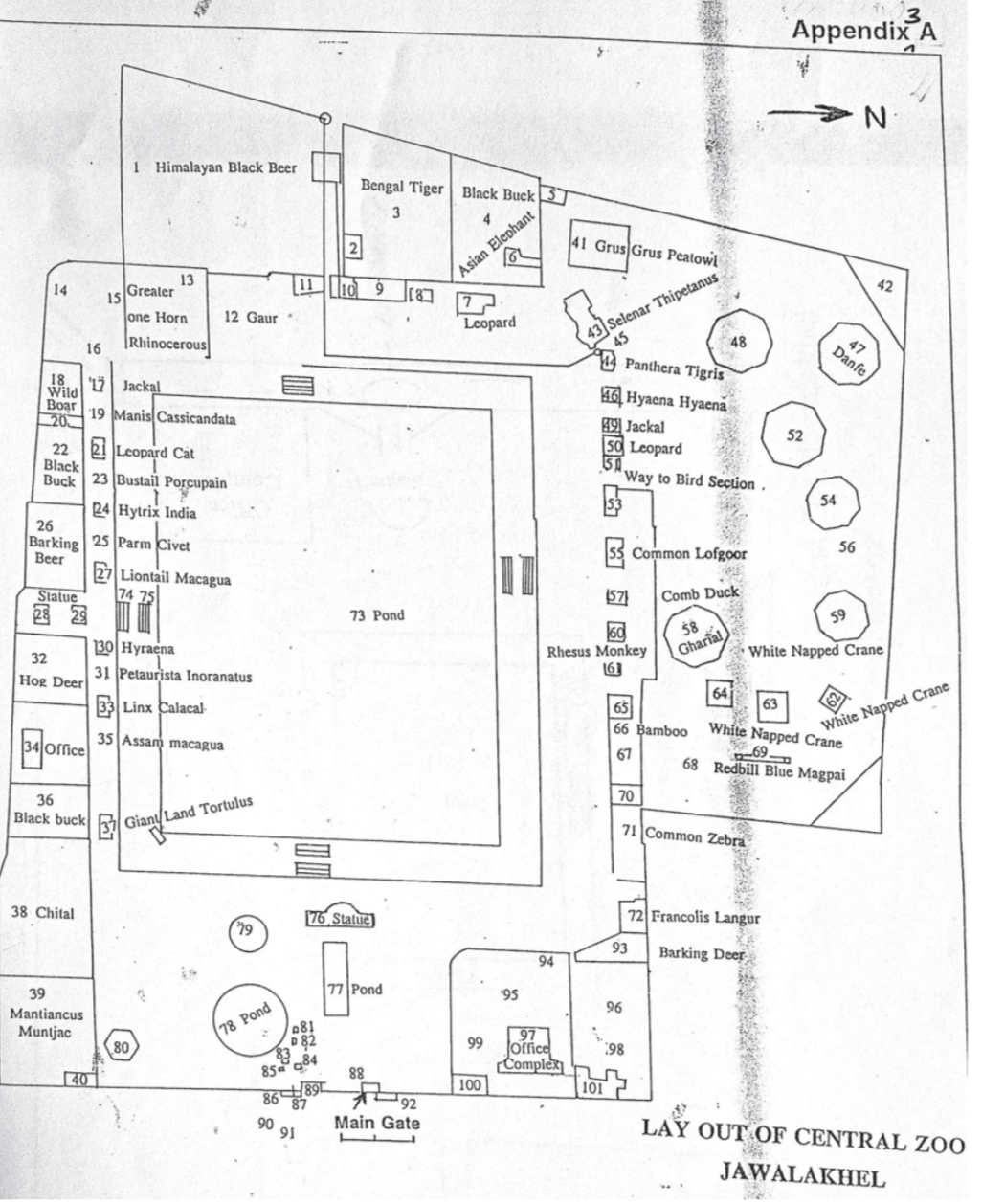

The zoo’s layout—except for the small plots of lands acquired later—that was in place when it came under KMTNC's management was, the present and retired zoo officials believe, mostly the same as it was built by Maheshwar and so offers a peek into how Juddha’s zoo must have been like. Pond in the middle of the ground surrounded by enclosures—the southern bank housing mainly larger animals, and cages for birds positioned on the northern banks.

From pigeons to the king of the jungle

What animals and birds did the enclosures at Juddha’s zoo house?

“We cannot tell for sure,” Koirala says.

Once it came under government ownership, the zoo was tossed from one institution to the other for lack of interest and knowledge on the right institution to manage it. Amid all this chaos, documents were possibly lost and the zoo has no concrete record about the animals that Juddha must have once taken amusement at, said Koirala.

Mukti Narayan Shrestha, 82, a retired secretary of the Nepal government, joined the Central Zoo in 1970 as a veterinarian when many original structures of the zoo were still intact. Shrestha also worked with an elderly khardar who, he says, was employed in the zoo since the time of Juddha and was about to retire when he joined.

“In those days where the purpose of menageries was exclusively for exhibition and pleasure with no regard for the welfare and recreation of animals and birds, the cages were tiny and iron-barred,” Shrestha says.

Elephant, horses, deer, monkeys, tiger, rhinoceros, clouded leopard, red panda, bear, palm civet (nir biralo), four-horned antelope, Himalayan goral, pheasants, Himalayan monal—from the mythical and the majestic, the gentle and friendly to the fiery and ferocious, Juddha’s zoo boasted them all, Shrestha says.

Shrestha’s account is not different from the anecdotes passed down to other retired and present zoo officials and the members of the Rana community, who also detail the rare and the exotic fauna, like the gharial crocodile and porcupine, even the jungle’s king—creatures, they say, that Juddha must have received from foreigners as gifts—appearing alongside domestic birds like pigeons.

Tidbits of published information also confirm that the zoo had a good collection of exotic birds and animals from Nepal and abroad. One such suggestion comes from Kalyan Shumsher’s ‘Shree Teen Juddha Mahima’ published during Juddha’s reign in 1943.

“One need not travel abroad to see the incredible birds and animals found in foreign countries,” he writes. “It will suffice to see [those creatures] right here in the zoo opened by His Holiness Shree 3 [Juddha] in Jawalakhel.”

Among these incredible creatures, one reigned supreme—lion, the king of the jungle.

For one, it would not have satiated Juddha to build a zoo and not have the jungle’s king exhibited in it. Juddha hence must have done everything possible to ensure one for the zoo. Infrastructure at the zoo suggests that the lion indeed lived at Juddha’s zoo or, in the least, during the Rana regime.

“Where bear habitat lies today, there were two dome-shaped attached enclosures with a holding room, constructed in the classic architecture that many enclosures in the British zoos had in the past. They had brick walls and lime plaster,” Koirala says. “These were built to house a lion in one cage and a tiger in the other.”

Near these enclosures stood another cage that remains intact today, with the head of a roaring lion carved out of the wall on the top of its iron bars. Zoo officials as well as members of the Rana community believe that Juddha had this exhibit built to specifically house a lion.

Remarkably, these Juddha-era infrastructural spaces are corroborated by a rare piece of photographic evidence. A 1946 photo of the zoo shows a lion while a Kathmandu mother and her sons stand in front of its cage.

Juddha’s place of piety and play

The zoo was not merely a space that Juddha sought out for amusement and retreat in the outpost of his palace; he also used this place to express his deepest affection.

This affection spills right at the zoo’s entrance, in the form of the life-size statue of Karma Kumari Devi, wife of Juddha’s elder brother and Rana Prime Minister Dev Shumsher. Karma Kumari stands tall in her regal costume shaded by a wide canopy. Juddha revered Karma Kumari because it was she who raised him and looked after his mother Juhar Kumari Devi after the death of his father Dhir Shumsher. On another prominent part of the zoo on the south-east, Juhar Kumari’s enthroned statue overlooks the pond. Juddha had commissioned the London-based sculptor Domenico Antonio Tonelli to cast these statues.

When Karma Kumari’s statue was unveiled is not clear, but Juhar Kumari’s statue was unveiled by Juddha amid a grand function in 1935 on Jawalakhel’s most auspicious day, Bhoto Jatra. It was attended by the British Resident Frederick Bailey.

“On June 28, 1935, at Jawalakhel Durbar… the pond nearby looked very scenic,” says a Gorkhapatra news report titled ‘Statue installation’ dated July 5, 1935. “Because it was the day of Bhoto Jatra of Machhindranath… and moreover since an ideal woman’s statue was being unveiled, there was a crowd of lakhs of people.”

Less than fifty metres from Karma Kumari’s statue stands a one-story building with a pagoda roof that today serves as the zoo’s meeting hall. Juddha, an avid gambler, found the scenic semi-wilderness covered in trees and filled with the sounds of wildlife to be a perfect place to relish the game. So he built a building with twelve doors on its four sides allowing him and his fellow gambling compatriots the freedom to enter through a particular door that they thought would bring luck. He called it his Juwa Ghar, the gambling house, and built it with the sole purpose of indulging in the game he loved.

Roar of lion reverberates in Kathmandu

The sounds of the animals and birds in the zoo rose up in the Jawalakhel sky. Every day, until much later in the 1970s, roar of the zoo’s lion (there were later other lions) diffused to far corners of the Valley, merging the zoo with the spirit of Kathmandu and informing the city folks of its presence.

But was the zoo open to the public as well?

“I think once it was built, the zoo was open for the public,” Subodh Rana said. “It is unlikely that Juddha Shumsher built such a large zoo and kept it only for his family.”

For one, Kalyan Shumsher mentioning that one “need not travel abroad to see the incredible birds and animals found in foreign countries” suggests that the public had at least some access to the zoo. Of course, the Newar community from Na:Tole, Pulchowk and surrounding areas were permitted inside the zoo on the days of their guthi functions on Basanta Panchami and Bhoto Jatra.

As the zoo was established at the back of the ground where Bhoto Jatra celebrations happen, it naturally filled with revellers on this day in addition to the guthi ritual observers as testified by the Gorkhapatra report. The photo of the mother and her sons also bear testimony that the zoo was not entirely closed to the public.

What is widely believed, though, is that the zoo officially came under government ownership after Nepal became a democracy in 1951. And it would still be a few more years before it was open to the public in 1956.

In 1945, Juddha gave up his power and eventually retired in Dehradun, India, where he died in 1952. With time, Jawalakhel Zoological Garden became the Central Zoo. It would take many avatars—a neglected site of crammed, unmaintained cages with sad eyes of emaciated creatures staring from behind the bars, a focal point of animal diplomacy, particularly during the period of monarchy, to, in its recent decades, a space of conservation and education.

When all this was happening, the city sprawled around Jawalakhel, subduing the lion’s roar with its noise. More wildlife from around the country and the world came—creatures captured from the wild, those sold by circuses, those rescued from traffickers. Fate would bring these creatures to the care of generations of Kathmandu folks, intertwining each other’s joys and sorrows. After the tale of Juddha’s Jawalakhel Zoological Garden, there would be these stories to tell. Sitting around a table inside Juddha’s Juwa Ghar, Koirala and other zoo officials begin unfolding these stories before me.

14.99°C Kathmandu

14.99°C Kathmandu