Interviews

The untold story of a Kumari’s mental well-being

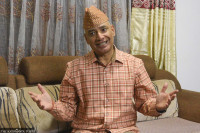

Chanira Bajracharya, a former Kumari, challenges stereotypes of isolation and mental strain associated with Nepal’s Living Goddess tradition.

Sanskriti Pokharel

The Kumari tradition has often faced scrutiny, especially from Western parts of the world, with critics viewing it as a form of child rights violation. Many believe that Kumaris are isolated within the confines of their homes, leading to potential long-term impacts on their mental health and well-being.

However, Chanira Bajracharya, chosen as the Kumari of Patan in 2001, challenges this narrative. She says, “It is incorrect to assume that Kumaris are destined to face mental health issues later in life. This is a misconception.”

In this conversation with the Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel, Bajracharya reflects on her unique journey, challenging stereotypes of isolation and mental strain associated with Nepal’s Living Goddess tradition.

Has being a Kumari contributed to your sense of self and well-being?

I was chosen to become a living goddess at five, which meant my childhood was far from typical. While most children experience carefree and playful years, my early life was centred around spirituality, discipline, and fulfilling a sacred role. In Hinduism and Buddhism, the ultimate aspiration is enlightenment—a state of inner peace and liberation from material attachments. Being a Kumari gave me an early start on this journey, helping me develop inner peace and a mindful, spiritual outlook.

Throughout my tenure, I was surrounded by immense love and respect. Even today, as an ex-goddess, I still receive the same admiration from those around me. The rigorous discipline I had to follow as a Kumari ingrained a strong sense of perfectionism in me, which has become a defining part of my character.

Countless people came to see me during those years, seeking blessings for various reasons. Some wished for career success, others hoped for academic achievements, and many sought healing from illness. It fostered a sense of compassion within me. I realised I was playing a unique role in their lives by contributing to their hopes and well-being. This sense of purpose has stayed with me even after stepping down from my role as Kumari. I still feel connected to those divine traits of compassion and perfectionism.

Moreover, my tenure did not hinder my education. I was fortunate to receive focused attention from my teacher, which helped me excel academically. This educational foundation is now supporting me in building my career.

Hence, being a Kumari from a young age until my mid-teens has profoundly contributed to my sense of self and well-being.

Did you feel any pressure or expectations from others due to your role as Kumari?

During my time as Kumari, I wasn’t explicitly “trained” on how to sit, speak, or present myself—it all came to me naturally. Once I wore the Kumari attire, I instinctively understood how to carry myself. I never felt pressured to act a certain way. Even on busy days with many visitors, I could rest if needed. At home, my parents treated me as Kumari rather than just their daughter, thoughtfully considering my needs.

What emotional support did you receive during your time as the Kumari?

Hearing the stories of former Kumaris who faced barriers to education and struggled to adjust after their tenure, my mother was initially worried.

But fate had different plans. My mother became my emotional anchor, providing steady support. Both she and my teacher would sometimes sit with me and gently remind me that soon I would start menstruating and would have to step down as Kumari. They prepared me, explaining that people would no longer worship me and that I’d need to transition to a “normal life.” These informal counselling sessions gave me immense emotional strength.

Were there any particular traditions or practices in place to nurture the mental and emotional well-being of a Kumari?

There were no formal practices, but emotionally, as Kumari, I was protected. Everything was there in place for me. I was admired, adored, and loved, which nurtured my mental and emotional well-being.

Were there moments when you felt isolated or disconnected from the outside world?

Living at home during my time as Kumari kept me from feeling disconnected. When my brothers returned from school, they would share stories about their day, their experiences, and what happened in class. My teachers would also talk to me about their students and classroom events. This helped me feel connected.

Interestingly, perhaps because of the “power” associated with being Kumari, I never really wanted to go outside, so I didn’t experience isolation or disconnection.

What I did feel I missed out on, though, were extracurricular activities. Education for Kumari was just beginning in my tenure, so learning games, sports, dance, and music wasn’t an option back then. I felt behind in those areas but quickly joined extracurriculars after my role ended.

Today, I’m glad to see the rules becoming more flexible, allowing current Kumaris to explore their interests.

After your time as the Kumari ended, how did you cope with returning to a 'normal' life? What challenges did you face during this transition?

After my time as Kumari ended, I was initially scared to walk outside. Crossing streets and navigating through crowded places was intimidating. At fifteen, my parents had to teach me how to walk confidently in public spaces again. Starting college was also an adjustment—learning, among many other students, felt unusual. However, I think my teachers informed my classmates about my background as a former Kumari, and they were very kind and considerate, which made the transition easier.

I consciously worked on staying calm in new and challenging situations. I reminded myself of my abilities and resisted self-doubt. Embracing positivity during this transition made a big difference in helping me adjust.

What advice would you give to the families of future Kumaris to support their mental well-being?

I encourage families to prepare their daughters well for the changes in reaching menarche. It’s essential to inform them early that their role as Kumari will end with this transition, so they’re ready when it arrives. Keeping them informed about the outside world is also vital, as it helps them adjust more smoothly. Parents should prioritise a gradual transition, offering regular guidance and steady emotional support to make this process as comfortable as possible.

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu